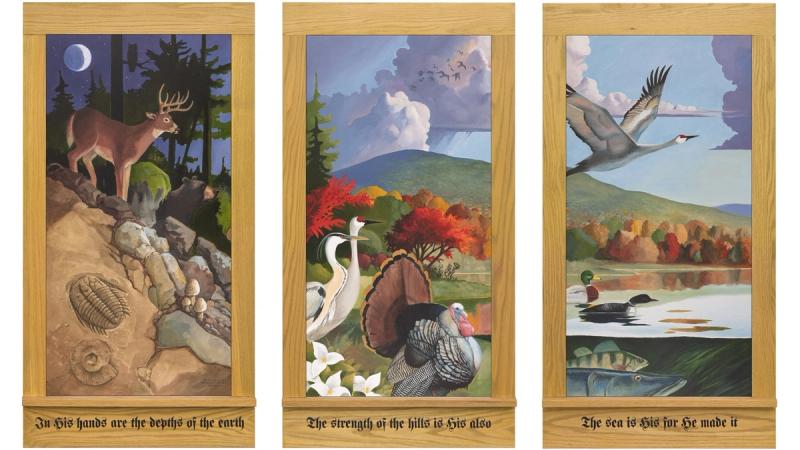

Image: Copyright © Edward Riojas. Used by permission.

The May-June print edition of Modern Reformation provided stimulating reflections on beauty, goodness, and art—something Protestants have not been known for historically. In his article, “Theology and Beauty: An Enquiry,” Bo Helmich laments that Protestants “have long been criticized for treating beauty with indifference, suspicion, and hostility.” He explains, “that critique goes something like this: in their zeal to curb the excesses of medieval Catholicism, the Reformers disparaged those areas of life in which beauty plays a vital role. Liturgy, art, nature, culture, the lives of the saints—all of it came to be viewed as idolatrous or ‘worldly’ in the pejorative sense of the term” (22). But what about those Protestant traditions that didn’t cast as much aspersion on liturgy and art? Does this customary anti-art narrative equally apply to Protestantism’s wide array of expression? Where does Lutheranism fit? I’ve asked Lutheran artist Edward Riojas for some input.

JP: Thank you, Edward, for agreeing to discuss Lutheranism and art. To start, could you tell Modern Reformation readers a little bit about yourself? How did you get to this point as an artist? Was art always an interest of yours?

ER: My journey, like many others, has been somewhat convoluted. I knew from childhood that I would become an artist. During high school and college, I had instructors and professors who demanded much of the student that deigned to become a representational artist. Of course, the time comes when an art student must make hard decisions regarding an otherwise-iffy career.

With a Fine Art degree in hand, I jumped head-first into the strange waters of the advertising world. A few later I transitioned to the newspaper industry, where I worked as an illustrator and graphics designer for more than 30 years. During that time, I also dabbled in a few sacred art projects, beginning with my own church.

The newspaper industry, however, was slowly taking a nose dive as an older generation of readers died off. I saw the end coming and eventually I was downsized. I wasted no time in promoting myself in both the secular and sacred art realms, but it became abundantly clear that the Lord had plans for me in the Church. I now work exclusively with churches, churchly institutions, and individuals connected to the same, and have a two-year waiting list for projects demanding my talents.

JP: Wow, that is a journey indeed. Being that your work is frequently connected to the Church in some way, how do you approach your role as artist theologically? What grounds your work as an artist?

ER: Forget fame. It is a humbling thing to work in the Church. Yes, I deal with pastors and elders and the like, but the responsibilities are immense when one considers that the boss is our Lord and Savior. Any fame is His; not mine. To that end, I strive to be true to Holy Scripture, and I must be crystal clear about it visually. In my opinion, abstract expressionism and non-objectivism have no place where the Word of God is concerned, because the road to heresy becomes very broad when the suggestion is made that, ‘It means what you think it means.”

JP: While a large portion of your work might be considered sacred art, you also create secular art in a variety of styles and mediums. How do you approach these two different realms of art? Is there a clear distinction, or is the sacred/secular division somewhat artificial?

ER: On one hand, there is a clear distinction, for each serves a very different purpose. On the other hand, all vocations demand a Christian’s excellence. A mother changes a diaper to the very best of her ability, so there is no excuse for me to cut corners as an artist. At the expense of sounding crass, failure in both vocations results in pretty much the same outcome.

JP: Much of your art functions as the visual focal point in church sanctuaries. What does a successful piece of church art accomplish? What is the goal for one of your pieces that adorns the walls of a church?

ER: The bottom line is that sacred art should underscore Holy Scripture. It should point us to the Bible. When done well, it helps to open our eyes to the beauty and depth of the Word. “Pretty” adornment simply won’t cut it where needy souls are concerned.

JP: Can you talk a bit about how art and architecture work together? In a sense, doesn’t architecture itself function similarly to art, and communicate theologically?

ER: Art and architecture do walk parallel paths in Christendom, as does sacred music. It’s a bit sad, however that well-meaning Christians sometimes err on the side of trends and appeal and frugality.

The medieval notion of laying out a church in the form of a cross, for example, confessed much. The parishioner could not escape the reality that he was literally standing on the cross. Without it, he wasn’t standing on much at all.

Yes, those same structures took a lot of deep pockets to build, but even that simple fact confessed what our Christian forebears considered of greatest importance. Today, the house of the Lord is often built to look more like His garage, and that is a shame.

JP: You mention medieval cathedrals and the great financial and theological effort that was put into them. Indeed, that does seem quite different from the industrial/warehouse feel of so many contemporary church buildings that dot the American landscape. Is this evidence of a different approach to things like beauty and art between Catholics and Protestants? Is the frequent juxtaposition of Catholics and Protestants when it comes to beauty and art an accurate distinction?

ER: This is indeed accurate. A wider picture reveals vast differences between Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Protestantism. These differences are not just general opinions, but are often deeply-seated within official doctrine. The differences have historically led to division and bloodshed.

JP: Following up on that, it seems to me, that even within Protestantism there are a variety of approaches to art. How would you describe the Lutheran approach? Is there such a thing?

ER: Lutherans usually place sacred art in the category of “Adiaphora” – meaning that it is neither commanded, nor forbidden in Scripture. That can sound like it is in a gray area or is somehow in the middle of the road. Lutherans do, however, view sacred art as a useful, edifying tool, without which we would be the less for it. Sacred art, however, is not always practical, and we must concede that a church’s roof be given more attention when in need of repair.

JP: To get more specific, a Lutheran-Reformed sticking point ever since the Reformation began has been the question of art and images of Christ in the church. When this issue was debated at the 1586 Montbeliard Colloquy, for example, Reformed interlocutor Theodore Beza explained, “Our hope is placed in the true cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, not in an image. For this reason, I confess that I whole-heartedly detest the image of the crucifix” (489). In the main, the Reformed tradition has continued a similar line of argument, which Helmich summarizes nicely: “eternal beauty is so far beyond our imagination and experience that any attempt to capture this beauty in religious art is not only doomed to failure but also dangerous because it always tends towards idolatry” (28). How would you respond to this position?

ER: The ‘Graven image’ thing is always brought up when addressing this issue. It’s a shame that both the bronze serpent and the skillfully wrought Cherubim atop the Ark of the Covenant—both commanded by God Himself —somehow slip under that radar of the debate. We must also consider St. Paul’s simple statement regarding the heinous Roman torture device, “We preach Christ crucified.” Across Protestantism—and even within Lutheranism—folks often lament, “Can’t we just get beyond the cross?” The reality is that man is a stupid, forgetful creature, and we constantly forget the cost of our Salvation. The fact is that we do a better job of displaying portraits of our dead relatives in our own homes than hanging images, in His own house, of what our Lord did for us.

Of course, we can neither fully, nor properly depict the beauty of Christ Jesus’ death for us poor, miserable sinners. Neither can we fully, nor properly sing His praises. This will always be so this side of Heaven. Yet we cannot help but sing of Him, and we cannot help but show the world that which He accomplished for us.

JP: You raise some good points there, about God himself commanding the creation of sacred art, though I think the Reformed response would be that those Old Testament images were acceptable since God ordered their construction. But still, if religious art always “tends towards idolatry,” it would seem perplexing for God to command it. Let’s unpack your larger point there about the centrality of Christ crucified. The incarnation and its cruciform pattern is not only central in the story of redemption, but also seems to bring about something quite decisive in the realm of beauty and art. Does this reality of God taking on flesh impact the Christian’s approach to art?

ER: In some ways, yes – especially for this artist. Throughout history, it has been fair game to artistically show that which is described in Holy Scripture. Because Christ Jesus took on human flesh as a true man, artists depict Him as one of us. Some images come close to the idea we have in our head; others, not so much. We must readily confess that any image of Him is at best a poor approximation, and we echo Job in saying that we will see our Redeemer, with our own eyes, at the last.

Images of Jesus are properly distinguished, however, by the addition of a tri-radiant nimbus, showing His true Divinity as a Person of the Holy Trinity. Not every artist uses the visual device, but it’s hard to place aside such a simple, but profoundly-confessional symbol.

JP: You’ve been so gracious with your time in answering these questions. Do you have any concluding thoughts on what Christians from different traditions can appreciate about art?

ER: I challenge folks to address art from where they are. Is there art or symbolism in the church which they attend? If there isn’t art, then search out Scripture to find out why [or why not]? If there is art, then what does it confess? The same questions can be asked when visiting other churches—especially other Christian denominations.

This may at first seem a silly exercise, but it is one more way to consider our Lord as we sit and as we walk along the way and when we lay down and when we rise up.

JP: That is great advice, since every church—whether they incorporate sacred art or not— utilizes symbols, space, and sound in some way. And all of it makes a confession—whether intentionally or not. As we draw to a close, where can people find your art? Are there any art projects you are especially excited about right now that you’d like to share with Modern Reformation readers?

ER: I always have several projects in various stages of development and several more that are waiting in the wings. I can’t always ‘show-and-tell,’ however, due to contractual obligations and the occasional commission for a surprise gift. Folks can get a good sense of my work at my website, edriojasartist.com, or they can mine through my public Facebook page, “Edward Riojas – Artist.”

JP: It sounds like you are busy indeed. God’s blessings on your continued efforts, and thank you again for sharing your insights.

Edward Riojas has been creating artwork professionally for over 35 years. He received a fine art degree, and then worked a three-year stint in advertising before spending nearly 31 years in the newspaper industry. Riojas has built a reputation in the secular and sacred realms as a masterful illustrator and fine artist. Today, his work is found in sanctuaries, institutions, private collections and markets throughout the U.S. and across the globe.

Joshua Pauling teaches high school history, and was educated at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. In addition to Modern Reformation, Josh has written for Areo Magazine, Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, Quillette Magazine, Salvo Magazine, and The Imaginative Conservative. He is also head elder at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, North Carolina.