The Worn Path or the Taller Grass?

Reading Soren Kierkegaard is a journey that takes the daring reader off the familiar path of Reformed theology and into the taller, wilder grass of spiritual existentialism. Through his writings I am brought into a whole new field of philosophical exploration that makes me feel at once both alive and bewildered. In general, I am convinced that most of my own reading should take place on the surer routes. For my own part, I have largely preferred to do the vast majority of my study in the works and writings of those saints who have most faithfully articulated the doctrines of Reformed Protestant theology.

I prefer the sure boundary markers that Confessional theology in particular provides. I need this. I need the structure, the signposts and guardrails. I take comfort in the confidence of knowing that I am following in the faithful, well-worn way of orthodoxy. I tread mostly where I can see the reliable footprints of men like Calvin, Edwards, Spurgeon, and Warfield. But I also think, with measured precaution, we should take an expand our routes and explore the trails that lie outside the bounds of our confessional traditions.

My guide on this journey beyond the landmarks and signposts has been the Danish sage and existential philosopher, Soren Kierkegaard (1813-55).

Exploring Kierkegaard

I first encountered Kierkegaard in college when I was forced against my will to take a class on modern, liberal theology. When I came across Kierkegaard’s work, Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, I found my soul convicted by the title alone. Soon enough, I found myself enchanted by a different kind of thinker whose journey into truth and Christian experience was both compelling and uncanny. Here was a writer who seemed to entirely forsake the tried and true categories that I had been trying so hard to master (effectual calling, justification, sanctification, etc.), but whose heart seemed to yearn for the presence of the Lord as did the writer of Psalm 63:1, “O God, you are my God; earnestly I seek you; my soul thirsts for you; my flesh faints for you as in a dry and weary land where there is no water.”

At a time when so many theologians were jettisoning the classical doctrine of God, deconstructing Scripture, and explaining away the power that is evident in the Gospel, Kierkegaard seemed to want to drive deeper into these things so that he might know God in purity and truth. He was not trying to demystify the Scriptures or do the work of the so-called “higher” critics, but seemed to be seeking something more profound than the others of his own age.

Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing

In Purity of Heart, Kierkegaard challenges the reader to confront the variegated and contradictory aims of life. Rather than having a heart that is split across many dreams and desires, the pure heart is that which, as James 4:8 exhorts, refuses to be “double-minded.” Kierkegaard calls this single-hearted devotion “willing the good in truth.” This is the highest end of man. To will the good in truth, the individual must confront a number of anomalies in his own heart: false motivations, fears, and the pursuit of broad acceptance. Remorse and regret are friends who lead the soul towards more honesty; they are to be embraced as guides on the journey. But he who wills the good in truth for the sake of recognition or earthly reward does so duplicitously. He will never attain it. Even worse is the man who pursues the good out of mere fear of punishment. The one who seeks the praise and honor of men is worse than double-minded, he is “thousand-minded.” He lives for an utter impossibility. This kind of mediocre human existence will be thwarted by innumerable excuses. Time will prevent him from entering into true contemplation. He skims across the surface of life, wasting precious time in banality.

Throughout the work, it seems obvious enough that seeking the Good in Truth is really the pursuit of a life of total submission and entire resignation to God as Lord. But just when I, as a Reformed reader, want Kierkegaard to point to the familiar signposts and landmarks that I already know (“The chief end of man is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever!”), he refuses and darts away. He takes me deeper into the tangled brush of my own thorny heart. He disdains traditional forms of language and doctrinal categories, as helpful as they may be. In his attempt to encourage spiritual maturity, both in himself and in his readers, he eschews standard formulations of doctrinal knowledge to forge his own way forward. He wanders away, waiting to see if any readers will follow. Reformed readers will find themselves frustrated from time to time that Kierkegaard almost never speaks in what we would consider to be the “proper” theological categories. He invents an entire new vocabulary to describe some of the same truths, but with different words. Instead of soli deo gloria, he speaks of willing the good. Instead of the Incarnation, he speaks of the Paradox or the Absurd. Instead of human finitude, he speaks of dread and anxiety. Idolatry is “double mindedness.” As I read, I don’t always agree with him, and often find myself fighting against him, pulling back towards the signposts. I scratch out some of my better objections in the margins of his works. I am more combative and alert than I would be when reading our confessional divines, but trudge forward bewildered and amazed as well to go where he goes and see what he sees.

Kierkegaard’s Primary Structures

In Reformed soteriology, my comfort zone, we often speak of the ordo salutis, or the order of salvation. We draw this from passages like Romans 8:28-30. In general, we speak of the logical progression of predestination, effectual calling, regeneration, faith, justification, sanctification (both definite and progressive), and finally glorification. As you may already guess, Kierkegaard makes very little—if any— use of these traditional categories, and sketches out his own morphology of salvation instead. His three stages are the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. What follows is his general rubric used throughout several of his works.

Kierkegaard tells us that the natural man is at first in a state of aesthetic orientation. He is overwhelmed with allure for the things of this world. He is driven by his senses and pulled like a magnet to the here-and-now. His passion is to taste, hear, and smell as much of this world as he can. He seeks to be affirmed by others and enjoys being passively entertained as a spectator more than anything else. He is a thrill seeker, and an adventurer, but in the end there is no new experience that can satisfy the growing weariness in his soul. He finds himself ever and always needing newer thrills. Greater adventures, new restaurants, the latest movie; he wants it all, and he wants it now. He finds himself growing only duller, however, and his heart aches for something more. A state of anxiety washes over his consciousness as he realizes the once-bright and vivid colors now only present in shades of gray. The aesthetic observer is left empty and alone. He wallows in despair.

By a leap of faith and a determined will (paradoxically also a gift of God) he jumps levels and finds himself in the world of the ethical. Kierkegaard emphasizes the process of becoming rather than static stages however, and sometimes one moves forward and back, shifting and halting. Nevertheless, the ethical stage is a new horizon as greater concerns than oneself begin to dawn. The more mature individual thinks in terms of universal categories — the ethical duty of humanity sets him on a course towards self-realization. All the while, he is becoming a more truly individual individual. He desires a purpose greater than his own life. He finds himself consumed with issues of more global significance. He wants to pursue justice and a life of rectitude. Personal responsibility and meaning sound like alerts in the conscience. But again, he finds himself woefully finite. His mortality is the ultimate confrontation. He cannot either fulfill or participate meaningfully in what he now begins to fear is most significant of all, something eternally worthy.

Here again, Kierkegaard diagnoses man’s need as the need for another leap. This leap is the leap of faith. Faith for Kierkegaard is both a gift and an act. Of course, he is not pulled into either Calvinism or Arminianism on these points. His conception of faith is a tertium quid. Increasingly self-aware, the soul is suddenly swept up by God and a determined leap of the will into the third and greatest stage—the category of the religious. He can no longer ignore God. His creatureliness is painfully obvious. Early attempts at prayer are thwarted and impotent, and yet he is pulled in further and deeper. Eternity weighs heavily on his heart, and he realizes that his mortality is a pressing issue. The Creator/creation distinction weighs dreadfully upon him, like the irresistible gravity of an invincible blackhole. Once again, however, he finds himself mired in dread and anxiety. He can do nothing. He is nothing before the greatness of God. In some ways, his dread is now more intense than he felt earlier in prior stages of his movement. He is now truly aware of himself and has become a true individual person—he is utterly alive and aware—but is swamped still in sin and suffering. The more he contemplates, the more he needs relief from such angst!

There is one final leap to go however.

The Paradox of Religion B

The religious stage, we are told, actually breaks open into yet a new field altogether. Kierkegaard moves from what he rather mundanely labels “Religion A” to “Religion B.” Religion B is deeper, more profound, and still more beautiful. Here, the soul seizes upon the great Paradox (a key term in Kierkegaardian thought): the incarnation of the God-Man, Jesus Christ. For Kierkegaard, the doctrine of the incarnation is the highest truth that can be pursued. It is true because it is the deepest and most real Good in the universe. He seems to ignore much of the modern liberal pursuit to discover the so-called “historical Jesus,” and instead leaps entirely over the historical crevice of Lessing’s ditch into which many other minds in his time fell. Kierkegaard grabs the reader’s hand and pulls him down to his knees so as to surrender the soul to the Absurd, the truth that God became man in Christ. The Paradox is too good not to be true. That the only living God would enter time and space to become man—to take part within the universe that He has made—must be accepted as the ultimate reality. It demands personal surrender. All else melts away under this glory. Having reached Religion B, the soul’s work now is primarily to renounce the self in what Kierkegaard calls “infinite resignation,” submitting entirely to the glory and joy of the Paradox. Prayer, then, is not so much about attempting to manipulate the will of God to obtain results (making prayer “requests” or “petitions”), but to provide a matrix in which the soul can resign and submit to the Good of this higher plane of truth. God as Heavenly Father wills only good for His children, a theme very common in his printed prayers. God can be trusted to overcome our despair.

What About the Communion of the Saints?

Kierkegaard certainly has much to say that is helpful. His model for surrendering to the Absolute absolutely, and the Relative relatively is a high yield observation. This is nothing other than exhorting readers to “seek first the Kingdom of God” (Matthew 6:33). Error comes surely to follow when we surrender to the Absolute relatively (for this is lukewarmth), or to the Relative absolutely (for this is idolatry). But I cannot follow Kierkegaard everywhere he goes. He wallows too long in the muddy places, and leads the reader into the thorny brier patch of obsessive introspection at times.

Kierkegaard’s critique of the church is, even if accurate, is telling. It is probably true that the Danish state church in his day left much to be desired. He constantly accused it as a relentless critic. For Kierkegaard, the church of his time seemed anything but the family of faith and the living body of Christ. It was an unmitigated compromise, a mere human institution, almost devoid of real truth. The organized church, he holds, is but a cheap imitation of the real experience that can be pursued within one’s own soul. For him, much of our cherished historical doctrine is nothing other than a diversion from a real pursuit of an individual and active faith. I fully appreciate his concerns for the spiritual vitality of the church, and I join him in criticizing a lukewarm church, but his critiques reveal a deeper problem: his relentlessly personalized existentialism and singularly pursued individualism. It seems to me that Kierkegaard has far less place in his theology and philosophy for a horizontal dimension of the faith. Kierkegaard conceives of authentic faith as primarily inward and upward, which is to say a search into oneself, where one’s relationship to the divine becomes absolute. But Kierkegaard places very little emphasis on the horizontal and outward dimensions of the faith in service to others, with compassion, and evangelism.

Without the church, I don’t know how else we can learn to love, or fulfill any of the many “one another” texts of Scripture (Romans 12:10; 1 Corinthians 12:25; Galatians 5:13; Ephesians 4:2). Without the church, we are all too alone in the real world. Kierkegaard’s famous “knight of faith” is truly alone with the infinite God; but the Old and New Testaments provide a greater picture of community. Even in his famous interpretation of Genesis 22 in Fear and Trembling, Abraham is never truly alone. The story is impossible to tell without Isaac.In his search for spiritual authenticity and true experience of the divine, Kierkegaard so highly prizes his own inward journey that he seems to have entirely forgotten what the Apostle John writes: “anyone who does not love his brother, whom he has seen, cannot love God, whom he has not seen” (1 Jn 1:4).

For some, Kierkegaard will prove to be a tough read. His philosophy is heavy, and made more difficult by the fact that he writes from various voices or perspectives within his own canon. He multiplies pseudonyms. For others, his writings on the soul will be a welcome encouragement to buoy one’s own spiritual life with his robust illuminations of prayer and meditation. For still others, his refusal to speak in our properly well-defined doctrinal categories and theological constructs will be confounding. But whether or not one chooses to engage with Kierkegaard, it is wise to learn to read outside of one’s own theological tradition, even if the purpose of such reading is to remind us how grateful we are for our own tradition. Theological students, ought to learn to read well Origen, or Julian of Norwich, or Henri Nouwen. As for me, I plan to continue to spend most of my reading time with orthodox confessional believers like Vos, Murray, and Machen, but will from time to time wander into the taller grass and the thicker brush, risking burrs and pickle-bushes to consider the lilies with Soren Kierkegaard.

Matthew Everhard is the Pastor of Gospel Fellowship PCA. He is the author of Hold Fast the Faith: A Devotional Commentary on the Westminster Confession of Faith, as well as A Theology of Joy: Jonathan Edwards and Eternal Happiness in the Holy Trinity, and has an active YouTube Channel content on books, Bibles, and Reformed theology.

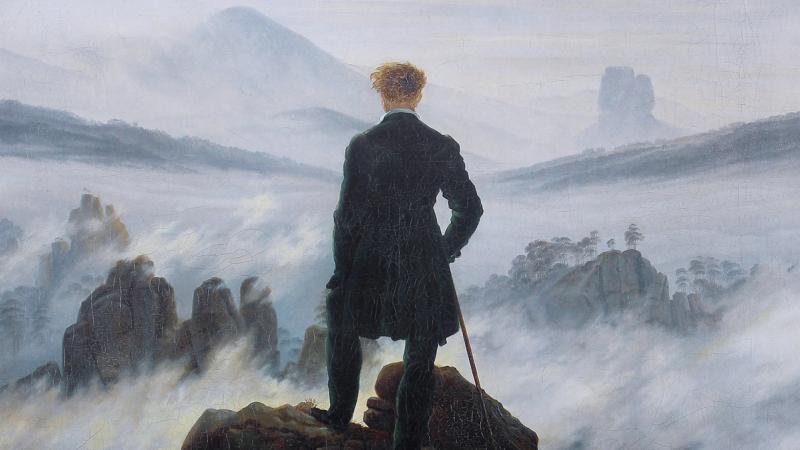

Image: Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich (1818). Public Domain {{PD-US}}, cropped by MR.