A lively debate over how central Christian worldview thinking should be has been going on for many years. Some posit that worldview is the catalyst that brings Christian doctrine into faithful practice, through applying biblical teaching to cultural issues. Take for example, Al Mohler’s daily program The Briefing, which opens each day with, “this is The Briefing, a daily analysis of news and events from a Christian worldview.” Others worry that focusing on worldview might truncate Christian truth into a series of intellectual arguments or position statements, ignoring the larger principles of habituation, practice, and piety, which lead to Christian fidelity and perseverance. Jamie Smith’s Desiring the Kingdom published in 2009 comes to mind, which Matthew Lee Anderson aptly summarized at the time for First Things in “Why Worldview is Not Enough.” I hesitate to call these two groups “camps,” since they aren’t mutually exclusive. Christianity surely involves both mind and heart, ideas and actions, thought and habit—and it seems to me that these two viewpoints attempt to offset prior imbalances.

Whatever one’s views are on the merits of Christian worldview thinking, Nancy Pearcey has developed an important tool of cultural analysis that is useful for everyone. In what has become a signature element throughout her work, Pearcey focuses on how modern society splits virtually all aspects of life and thought. While there is a risk of oversimplifying everything into “splits,” or pigeonholing complex philosophical traditions into these pre-made dualisms, Pearcey’s ability to uncover such splits helps Christians to recover a more robust telling of the Christian story and the importance of the unified human person couched within that story. Pearcey’s three major works all employ the split in addressing a wide range of issues.

Societal Splits: Value-Fact

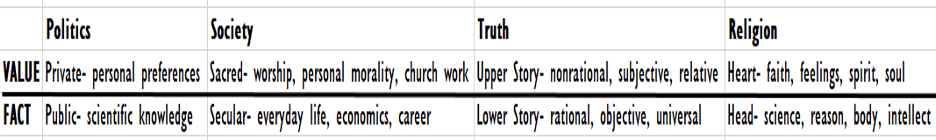

In Pearcey’s first major book Total Truth, she traces the development of dualistic ways of thinking so prominent today, keying in on the value-fact split. Charting it would look something like this:

Pearcey argues that the value-fact split is evidenced any time one’s moral positions or religious beliefs are framed as personal preferences or inner feelings, which conveniently cordons off Christianity in the upper realm, separate from the public square. Without resorting to outright persecution society can politely dismiss Christianity, and all-too-often Christians assume as true this very split, which undercuts their truth claims. Pearcey explains, “The reason that Christians often fail to break through that relativistic framework is partly that we ourselves have absorbed a form of religious relativism—in practice, even if not in belief. By accepting the fact/value dichotomy, many of us have come to think of religion and morality in terms of a privatized upper-story experience. If we privatize our faith, however, we will play right into the hands of the philosophical naturalists, who likewise relegate religion to the upper story” (203).

Pearcey offers examples of the subtle effects of this split. In education, she sees it in the acceptance of educational theories that are at odds with Christian doctrine. Pearcey recounts speaking at a Christian Educators conference on the Darwinian and relativistic roots of constructivist educational theory. After her address, a Christian school superintendent said, “All my teachers are constructivists—all of them.” Pearcey asked, “But don’t they realize what that means for their faith? …If knowledge is a social construction, then that applies to Christianity as well—it’s just a product of social forces.” The superintendent responded, “I know, I know. But constructivism is what they learned at the university under the auspices of the ‘experts,’ and they don’t question it. They just keep their religious beliefs in a separate mental category from their professional studies.” She concludes, “as a result of this compartmentalization, the teachers had unwittingly embraced a radical postmodernism that reduces all truth claims to merely social constructions” (242).

Pearcey also finds this split at work when life is divided along sacred-secular or private-public lines. Such a division is “not merely abstraction,” but has “a profoundly personal impact.” She continues, “when the public sphere is cordoned off as a religion-free zone, our lives become splintered and fragmented. Work and public life are stripped of spiritual significance, while the spiritual truths that give our lives the deepest meaning are demoted to leisure activities, suitable only for our time off. …Unless Christians tackle this attitude head on, our message will continue to pass through a grid that reduces it to an expression of merely psychological need” (64-65, 203).

Philosophical Splits: Mind-Matter

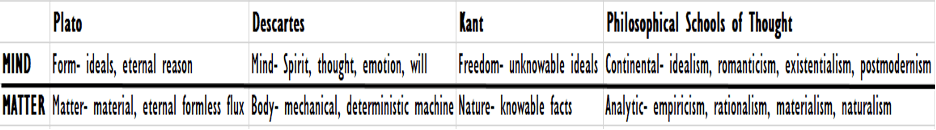

In her second major work, Saving Leonardo, Pearcey analyzes philosophy, art, and popular culture and makes clear that philosophy is no ivory-tower enterprise. Philosophy is on display in music, art, movies, and media that we consume in such large quantities. Pearcey shows how this is the case by widening the lens of the value-fact split central in Total Truth, to tackle one of philosophy’s perennial questions: the relationship between mind and matter. Her mind-matter split could be diagrammed as follows.

Pearcey explains how society today incorporates aspects from both sides of the mind-matter divide and creates an eclectic worldview based on modernist-materialist assumptions in the lower story (Matter), and postmodernist-idealist assumptions in the upper story (Mind). Pearcey suggests that what results is a Darwinist view of the material world with human bodies driven by instincts, while at the same time elevating the ideational constructions of the human mind when it comes to identity.

Pearcey analyzes a variety of art forms and though some of the movies are a bit dated now, the panoramic tour she provides of art history and its connections to philosophy is well worth the effort. Pearcey makes a strong case that using the split to navigate the world “encourages Christians to enjoy the aesthetic qualities of art, while at the same time providing them with tools for critical analysis of the motivating ideas.” She also makes clear that “Christian artists have worked in virtually all artistic styles. Biblical truth is so rich and multi-dimensional that it can affirm what is true in every worldview, while at the same time critiquing its errors and transcending its limitations. In this way, Christianity makes possible the greatest intellectual and artistic freedom” (101).

She offers the life-story of C.S. Lewis as a powerful case-in-point. The inner tension between reason and romanticism was palpable for Lewis and others who thought deeply about what could possibly sustain meaning for human life in the face of the growing scientific and industrial mindset. What ultimately crosses the chasm is Christianity’s message of the enfleshed God. All of the dualistic divisions that Pearcey so powerfully uncovers in her books are resolved in the unity of the Christian message. She writes, “Christ’s life, death and resurrection were events that occurred in the physical world, testable by the same means as any other historical event. Yet they were also the fulfillment of the ancient myths that Lewis had always loved…. In other words, the great events of the New Testament have all the wonder and beauty of a myth. Yet they happen in a specific place, at a particular date, and have empirically verifiable historical consequences. The realm of empirical fact is imbued with profound spiritual meaning. Christianity unifies the two realms. The biblical worldview fulfills both the requirements of human reason and the yearnings of the human spirit” (210-211).

Anthropological Splits: Person-Body

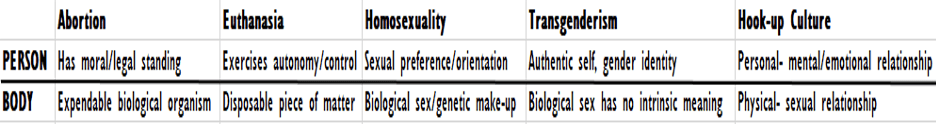

In her most recent work, Love Thy Body, Pearcey extends the value-fact and mind-matter split to all of the relevant issues involving the human body today, and finds that the common strand connecting them is a dualistic understanding of the human person. In what might be considered an accessible extension of Pope John Paul II’s profound Theology of the Body, Pearcey unpacks how dualism lies behind abortion, euthanasia, hook-up culture, homosexuality, and transgenderism. Pearcey’s perspective on the goodness of the human body moves Christian morality beyond just a list of dos and don’ts. As Abigale Favale notes, Pearcey’s “holistic, incarnational paradigm…[provides] what we sorely need: not mere repudiation, whether of purity culture or the pop-Gnostic secular alternative, but rather a resounding yes to Christianity’s incarnational cosmos and the human person’s place within it.”

Pearcey’s application of the split to current issues surrounding the human body and human person is quite persuasive. She contends that the core problem is personhood theory, which posits a two-tiered view of human beings. Pearcey writes, “To be biologically human is a scientific fact. But to be a person is an ethical concept, defined by what we value” (19). In one sense, this is not a new problem, as Pearcey connects it to many “-isms,” including Gnosticism, Platonism, and Descartes’ mind-body dualism. But Pearcey goes further and unpacks how this underlying dualism leads to a fragmented and harmful view of the human person. In diagram form, it would look like this:

In every case, Postmodern/Constructivist theory is driving the autonomous self to impose its own interpretations on the physical body which is understood as having no intrinsic identity or purpose. By separating the person from the body, modern society can have its cake and eat it too, as humanity comes untethered from the freedom of forms into the slavery of self-made identities. But this is an empty promise as it leaves people searching for the ultimate meaning found in a holistic understanding of the human person as created in the image of God with body and soul united.

Conclusion

While one might quibble with the way Pearcey categorizes certain philosophical traditions to fit into the split framework, its explanatory power and versatility as a basic tool is impressive. The split is easy to remember, with application to Christian living and a wide variety of topics.

The split has apologetic utility as it enables Christians to understand others’ views from the inside out. As Pearcey writes in Love Thy Body, “it is rarely effective to criticize someone else’s view from within your own perspective. That just means they disagree with you. It is much more persuasive when you step inside the other person’s perspective and critique it from within, showing how it fails on its own terms. To do that, Christians have to become familiar with secular worldviews and learn to uncover their dehumanizing and destructive implications” (261).

The split also helps Christians embrace all of their vocations and duties as work unto the Lord. Christians are freed to find meaning in the mundane, knowing that every task in some way is our participation in the creative work of God in the world. This perspective, Pearcey says in Total Truth, “unifies both secular and sacred, public and private, within a single framework” and reminds us “that all honest work and creative enterprise can be a valid calling from the Lord….These insights will fill us with new purpose, and we will begin to experience the joy that comes from relating to God in and through every dimension of our lives” (65-66).

Finally, the split fortifies Christian formation and catechesis. As Pearcey puts it in Saving Leonardo, “young people are confronted not only by moral temptations but also by philosophical temptations—fleshed out in the idiom of pop culture. For young people, learning the skills of worldview awareness can literally mean the difference between spiritual life and death. Ideas exert enormous power when set to music in a YouTube video or translated into glowing images on the theater screen” (251).

The split helps return Christianity to its rightful place as a compelling metanarrative that reunites the dichotomies of modern life in the person of Christ and the drama of Creation-Fall-Redemption. Christianity is much more than believing in Jesus in your heart, or following a list of moral imperatives. It is what humanity was designed for; communion with God and with one another—lived out with the mind and the body.

Joshua Pauling teaches high school history, and was educated at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. In addition to Modern Reformation, Josh has written for Areo Magazine, Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, Quillette Magazine, Salvo Magazine, and The Imaginative Conservative. He is also head elder at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, North Carolina.