For a large portion of the church catholic, Sunday, June 7 marked the commemoration of Trinity Sunday. Traditionally, this annual event in the life of the church focuses on the profound mystery of the Holy Trinity in the hymns, prayers, and readings of the day, and commences the longest season of the church year, entitled simply as Trinity. But perhaps most notably of all, on Trinity Sunday many churches confess the faith together using the lengthy and daunting Athanasian Creed in place of the Nicene Creed. No matter what one thinks about liturgical worship or the church calendar, the glories of the Triune God are for all Christians to embrace and celebrate with deep doxology. Exploring the context and content of the Athanasian Creed helps us do just that, and furthermore protects us from the re-emergence of ancient Christological heresies against which such creeds formed in the first place.

Context of the Athanasian Creed

As Christianity emerged in the Roman Empire, its early identity was forged in the crucibles of persecution and heresy. Paul Johnson explains in his sweeping work, A History of Christianity, in the first few centuries A.D., “varieties of Christian-gnosticism” and “revivalist sects grouped round charismatics” were widespread, and what has become Christian orthodoxy was not always in the majority (52). The environment of sporadic persecution and competing factions changed dramatically in 313 A.D., with Constantine’s Edict of Milan, by which “the Roman Empire reversed its policy of hostility to Christianity and accorded it full legal recognition” (67).

Now fully out of the shadows, public debates over countless Christian doctrines emerged and were addressed at contentious church councils held throughout the empire as need arose. Christian orthodoxy was solidifying, yet also embarking on a tumultuous relationship with the state that proved to be both a bane and blessing. As Johnson summarizes, if not oversimplifies, “In the second century the Church had acquired the elements of ecclesiastical organization; in the third it created an intellectual and philosophical structure; and in the fourth, especially in the latter half of the century…it began to think and act like a state Church” (99).

In the midst of these changes, the time had finally come to properly address the persistent puzzle of the divinity and humanity of Christ, and by extension the nature of God himself as Trinity. Since Christianity’s earliest days, different schools of thought attempted to solve the Christological conundrum, and in the fourth century, Arius’ teaching that Christ was an exalted creature, with the accompanying refrain “there was a time when he was not,” was spreading. After Alexander sent a circular letter to his fellow bishops condemning Arius’ teaching, the council of Nicaea convened in 324-325 A.D. Among those gathered together was a young Athanasius, who would eventually succeed Alexander as bishop of Alexandria.

While not the author of the Nicene Creed, Athanasius’ theological writings constantly attend to how Christological and Trinitarian understandings practically effect our redemption. As J.N.D. Kelly expounds in Early Christian Doctrines, Arius “started from a priori ideas of divine transcendence and creation,” and argued that the Word “could not be divine because His being originated from the Father. Since the divine nature was incommunicable, He must be a creature” (243). For Athanasius, however, “philosophical and cosmological considerations played a very minor part, and his guiding thought was the conviction of redemption. …Hence the Word himself must be intrinsically divine, since otherwise He could never have imparted divine life to men” (243). This steadfast and singular focus on the redemptive implications of how one understands the Trinity was the theme of Athanasius’ turbulent life.

At Nicaea, Alexander and his protégé, Athanasius, carried the day, immortalizing the poetic, yet precise creedal phrases meant for rhythmic public recitation and memorization:

And in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the only-begotten Son of God,

begotten of His Father before all worlds,

God of God, Light of Light,

very God of very God,

begotten, not made,

being of one substance with the Father,

by whom all things were made;

And then comes the section that most epitomizes Athanasius’ driving concern:

who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven

and was incarnate by the Holy Spirt of the virgin Mary

and was made man;

and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate.

Despite such successful formulations, within a decade after Nicaea, the tables turned. Constantine secured Arius’ reinstatement, and Athanasius endured a series of exiles for his refusal to readmit Arius and his followers. Arius now seemed victorious, especially in the East (Johnson, 92, 103). For most of the remainder of Athanasius’ life, it was “Athanasius contra mundum” — Athanasius against the world.

Though Athanasius died in 373 AD with no victory in sight, his ideas continued percolating thanks to his writings—especially On the Incarnation and Against the Arians. It was most likely in the fifth century when the creed that bears his name was written as a full-orbed defense of the Divinity of Christ and the Trinity. Athanasius’ long-delayed triumph finally arrived.

Content of the Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed begins in Latin with, Quicumque vult – “whosever wills.” Following traditional liturgical naming conventions, the opening Latin phrase became a title of sorts for the creed. The creed starts:

Whosoever wishes to be saved must,

above all, hold the catholic faith.

Whoever does not keep it whole and

undefiled will without doubt perish eternally.

Doctrine matters; holding the catholic faith “whole and undefiled” includes confession of and faith in the Christ of God. The creed continues:

And the catholic faith is this,

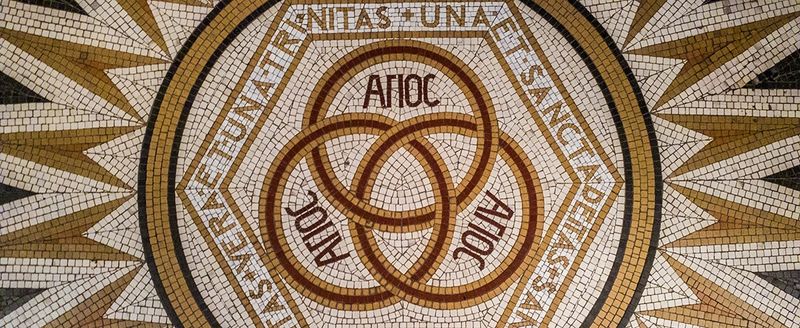

that we worship one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity,

neither confusing the persons nor dividing the substance.

For the Father is one person, the Son is another, and the Holy Spirit is another.

But the Godhead of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit is one:

the glory equal, the majesty coeternal.

The essence of the Christian faith is the Trinity; from creation to eschaton, the Trinitarian God is at work.

The creed then moves into a section regarding the distinct persons, yet unified oneness within the Trinity, with the repeating refrain, “yet there are not three…but one…” However, such Trinitarian explanations would be irrelevant without the incarnation of the Son to redeem humanity. Thus the creed shifts to Christology, expanding upon the Nicene framework to further define an orthodox understanding of the two natures of Christ.

He is God, begotten from the substance Of the Father before all ages;

And He is man, born from the substance of His mother in this age:

Perfect God and perfect man,

Composed of a rational soul and human flesh;

Equal to the Father with respect to His divinity,

less than the Father with respect to His humanity.

Although He is God and man, He is not two, but one Christ:

One, however, not by the conversion of the divinity into flesh,

but by the assumption of the humanity into God;

one altogether, not by confusion of substance,

but by unity of person.

For as the rational soul and flesh is one man, so God and man is one Christ.

For the salvation of mankind, Christ must be unified as the God-Man, as Athanasius describes in On the Incarnation,

What, then, was God to do? What else could He possibly do, being God, but renew His Image in mankind, so that through it men might once more come to know Him? And how could this be done save by the coming of the very Image Himself, our Savior Jesus Christ? Men could not have done it, for they are only made after the Image; nor could angels have done it, for they are not the images of God. The Word of God came in His own Person, because it was He alone, the Image of the Father Who could recreate man made after the Image. In order to effect this re-creation, however, He had first to do away with death and corruption. Therefore He assumed a human body, in order that in it death might once for all be destroyed, and that men might be renewed according to the Image. The Image of the Father only was sufficient for this need (12).

Contemporary Relevance of the Athanasian Creed

Lest we think such lengthy and heady doctrinal specificity is unnecessary in our day, consider some of the ways the Trinity is misunderstood by many Christians. According to a 2018 survey, 59% view the Holy Spirit as an impersonal force. Or perhaps even more disconcertingly, the same survey found 78% of evangelicals agreed with the statement that “Jesus was the first and greatest being created by God.” Theology professor Christopher Hall quips, “Seventy-eight percent agree with Arius—the arch-heretic of the fourth century. Quite shocking. The church fathers wouldn’t be pleased.” To say the least, the old Christological and Trinitarian heresies are alive and well, and we would do well to remember the lessons from Athanasius.

As Athanasius reminds us, the Trinity is not an appendix to Christianity for those of an intellectual bent; it is the lifeblood of the faith, without which we’re only left with generic theism, and thus with no salvation either. Michael Reeves explains in his wonderfully accessible yet astute book, Delighting in the Trinity, “Given all the different preconceptions people have about ‘God,’ it simply will not do for us to speak abstractly about some general ‘God.’…Neither a problem nor a technicality, the triune being of God is the vital oxygen of Christian life and joy” (18).

Athanasius grasped this vital truth in his lifelong battle with Arius. Arius started with the philosophical presupposition that God is the “Uncaused” being, and concluded that the Son must be a created being. Athanasius started with the Scriptural revelation that God is Trinity, and concluded that the Son must be fully God and Man. Reeves captures the differences well:

Believing that Arius had started in the wrong place with his basic definition of God, Athanasius dedicated the rest of his life to proving how catastrophic Arius’ thinking was for healthy Christian living….That is to say, the right way to think about God is to start with Jesus Christ, the Son of God, not some abstract definition we have made up like ‘Uncaused.’…Our definition of God must be built on the Son who reveals him. And when we do that, starting with the Son, we find that the first thing to say about God is, as it says in the creed, “We believe in one God, the Father (22).

With God as Father, love pours forth freely, intercoursing first among the three persons of the Trinity and then overflowing to humanity via the Son, who reunites us with the Father through the Holy Spirit. For God to be love, God must be Trinity. For humanity to be reconciled to God, God must be Trinity. Athanasius’ On the Incarnation says it well: “It is we who were the cause of His taking human form, and for our salvation that in His great love He was both born and manifested in a human body” (4). As Reeves elucidates, “without the Son, God cannot truly be a Father; thus alone, he is not truly love. Thus he can have no fellowship to share with us, no Son to bring us close, no Spirit through whom we might know him. …Athanasius had a God of love, a kind Father who draws us to share his eternal love and fellowship” (129-130).

So, as a large portion of the universal church begins the long season of Trinity, may we all remember Athanasius’ defense of orthodoxy, and most notably his exaltation of the Son, who by the power of an indestructible life defeated the power of death and was raised to new life, reconciling us with the Father through the Spirit. This is the work of our glorious Triune God, with glory equal and majesty coeternal, world without end, Amen.

Joshua Pauling teaches high school history, was educated at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. In addition to Modern Reformation, Josh has written for Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, Salvo Magazine, and The Imaginative Conservative. He is also head elder at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, North Carolina.