Eric Liddell of Olympic fame, immortalized by the 1981 Hugh Hudson film, Chariots of Fire, was more far than a principled and uncompromising gold medalist—he was an inspiring husband, father, and missionary who lost his life in a World War II Japanese interment camp within China. Lutheran pastor, Eric Eichinger, with Eva Marie Everson, recount these and thousands of other lesser known facts about one of Scotland’s greatest athletes in The Final Race.

Eichinger and Everson’s biography of Liddell is no Life of Samuel Johnson, but it’s not meant to be an intellectual or psychological account. Rather, it is a warm-hearted, inspirational, yet informative and chronological retelling of Liddell’s unusual journey into the limelight of international fame and headlining opportunities within the United Kingdom to a life of relative obscurity as an overseas missionary.

Liddell truly was a world-class athlete who, even today, would distinguish himself in sprint events and his other sport, rugby. He played for Scotland’s international rugby team in 1922-23 with natural blazing speed and almost no formal coaching. He won Olympic gold in 1924 for the 400-meter race and remained an elite short distance runner with a most unorthodox style and surprisingly little training. But it wasn’t athletic prowess that occupied the heart and mind of “The Flying Scotsman”. Rather, it was the love of God, a passion for the lost, and serving Christ with his wife and life.

Personal letters and other writings evidence that he eschewed all things celebrity-related and preferred the privacy of home and the company of trusted friends. He profited very little by way of his fame and declined all potential advantages of being a national hero and Britain’s most recognizable personality. Indeed, foremost on his mind was not how to parlay a career out of his Olympic feats but to where he could do more for Christ—England or China, where his father was a missionary before him. In this way, he stands as a curiosity to our current media and cultural obsession with self-serving wealth and fame.

Narrating his undergraduate years at the University of Edinburgh through the Olympic Games and the personal life that led him into service with the London Missionary Society, the authors develop Liddell’s spiritual and theological advancements, albeit without weighting the biography with technicalities or needless excursions. While neither a Presbyterian nor a Calvinist, the reader comes to find Eric Liddell’s Congregationalist beliefs were surprisingly elastic, moving him over time from pietistic Sabbatarianism (if not evangelical legalism), to a discovery of the doctrines of grace through, surprisingly, a Methodist colleague.

Eric was not an advanced theologian by any stretch. He was not a gifted teacher or winsome orator, but his earnestness and devotion resonated so clearly through his plain-style preaching that he captured his audiences and learned to proclaim the Gospel and properly distinguish it from the law, while distancing his content from inane decisionism. In this way, he matured away from Arminian beliefs toward Reformational beliefs, all the while maintaining loyalty to his Congregationalist roots. Readers will be impressed with the simplicity of his faith, especially when hardships of isolation, austerity of living, and even the persecution of illness descended upon him.

The untimely close of his life came under unusual circumstances, too. World War II finally encroached upon his Chinese outpost, prompting his return to Britain where he and his brother volunteered for the Royal Air Force. He was denied service and was instead relegated to a menial desk job. In time, he made his way back to Canada, where his wife and children safely resided. A series of decisions followed that brought him back to China, where the Japanese had invaded. For more than two years, Eric Liddell found himself under increasingly harsh interment conditions. He took it as his lot to serve, teach, and preach in Christ’s name until, at last, a cerebral anomaly—probably brain cancer—overtook him. He resolutely died in our holy faith, not having seen his wife and children for years due to imprisonment.

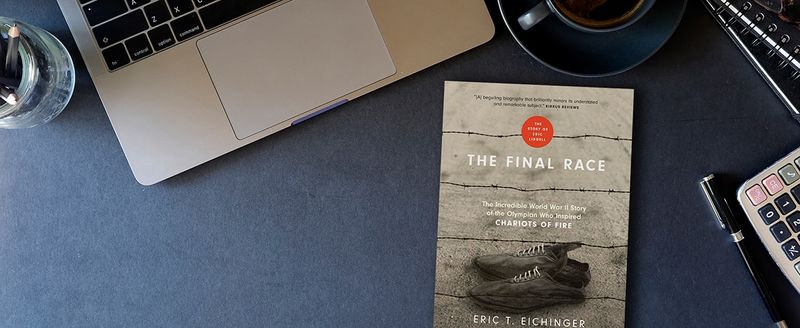

This is a book that parents can read with their children and one that will inspire and elicit a note of wonder for lovers of biography. It comes recommended, not because of the glitter of Chariots of Fire, nor because of Liddell’s one-time sabbatarian beliefs that stood contra mundo, but because it is a worthy and endearing story of Christian faith and service and perseverance that so strongly contrasts our trite gravitation toward the cult of celebrity for all the wrong reasons. Liddell offers many of the right reasons for remembering someone of fame, but more importantly, noble character.

John Bombaro (Ph.D.) is a Programs Manager at the USMC Headquarters. He lives in Virginia with his wife and children.

If you like learning about the notable figures of the age, you’re in good company—for the past 25 years, we’ve been interacting with leading personalities from all creeds and confessions, from Karl Marx and H.L. Mencken to Renée of France and Marie Durand. Subscribe to Modern Reformation and learn more about the men and women who have shaped Western thought and theology.