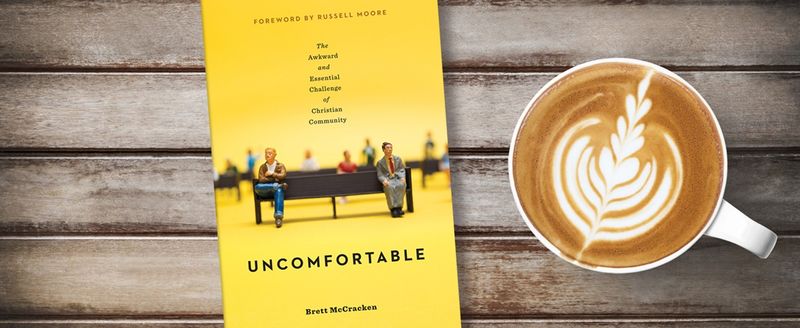

In the aptly titled Uncomfortable, author Brett McCracken touches on a phenomenon that most churches are dealing with in some shape or form: awkwardness. Why are people feeling discomfort in their churches, rather than right at home? Is there someone or something to blame? According to Uncomfortable, the problem is not that Christians feel uncomfortable in church – rather, the issue is that Christians expect to feel comfortable to begin with! McCracken deconstructs this idea that church is supposed to be a place of comfort by positing that at a fundamental level, Christians are called to places of discomfort, from the very doctrines the Christian believes to the very church they call home. From this foundation, Jesus is ushering His bride into heavenly realities and calling His church to put to death its old nature and as we all know, death is hardly a recipe for comfort. Rather than encouraging the elimination of the discomfort and awkwardness found in churches, McCracken calls the reader to embrace such states as spiritual training grounds.

While Uncomfortable’s ‘Introduction’ is much shorter than the other two sections (‘Uncomfortable Faith’ and ‘Uncomfortable Church’), it is the most impactful section of the book. It is there that McCracken lays out the vision of his “dream church” in startling detail. This “dream church” has biblical elements but is also very much shaped by his personal preferences (which he acknowledges)—the latter being what makes the concept of a “dream church” so dangerous. Without deeply considering what Jesus Himself has called His church to, Christians will often equate personal preferences with biblical principles and subsequently expect their churches to get in line with those preferences—all in the name of Jesus. The heart of man too often idolizes what is good as what is ultimate, and with church, that can affect a Christian’s commitment if the church doesn’t meet up to his or her now ultimate (and ultimately personal) standards. Christians probably have avoided thinking through this type of exercise, because it seems wrong—“Of course Jesus defines the church, not me!”—and yet, how do we know which desires for a church are biblical and not simply personal preference? In undertaking McCracken’s exercise, by writing (in detail and with honesty), personal desires for the ultimate “dream church,” and comparing such a list to the biblical church of Jesus Christ laid out in the Word, the Christian can begin to sift the wheat from the chaff in our own hearts.

‘Uncomfortable Faith’ reminds Christians that the very faith upon which the church is founded will lead it into the unknown and the uncomfortable. Christians too easily forget that throughout Scripture, Jesus warns His disciples of the persecution they will face and how the world will never accept them for their faith. In today’s technological age of on-demand products, services, and responses where convenience is king, it is quite easy to forget that the church does not exist for our comfort or (ultimately) to serve us. The call of the church is for self-sacrifice in light of the grace given to us by Jesus Christ.

Chapter Eight shines largely for the same reasons as the Introduction—McCracken makes himself vulnerable by sharing, with brutal honesty and specific detail, the types of people that make him feel uncomfortable. The level of depth that he goes into in describing such people is almost shocking because it feels sinful and unloving, but it proves to be valuable pedagogical tool. In addition to describing the folks he would rather avoid, McCracken also describes the people he would honestly rather spend time with. In making such comparisons, he indulges his humanly nature boldly but for a purpose—he encourages the reader to be honest with themselves through examining their own hearts and pinpointing their exact sins. It is hard to admit that it’s difficult to love your own church because of the people, but by taking an honest stance, McCracken creates rooms for others to do so as well, not for the sake of feeling justified in their dislike of their fellow church members, but to call them to depend on Jesus for a loving heart.

Uncomfortable is not without its flaws. In Chapter Six, McCracken oddly highlights the inter-church debate between Cessationists and Pentecostals. The chapter, titled “Uncomfortable Comforter,” does not quite stay within the spirit (pun intended) of “Uncomfortable Faith.” McCracken admits that charismatic gifts make him feel uncomfortable but that has not stopped him from embracing a more charismatic point of view. He writes, “Do I fully understand tongues? No. But again, a willingness to grow in the Spirit includes a willingness to cede ‘Everything must make sense!’ rationalism. The ways of the Spirit can be wacky and weird, but they build up the body in wonderful ways.” The problem is not with McCracken’s view, but how he frames the issue. His general framework for helping Christians to reflect on the discomforts they may experience in church doesn’t help them consider how to resolve issues concerning genuine Christian disagreement. When McCracken applies his framework to the conflict of worldly comforts versus Christian principles, the book is extremely valuable, but it’s less helpful when discussing biblical doctrine and the degree to which various views may be considered scripturally faithful. There will always be arguments and honest, hard dialogue is required in order for the church to evolve towards a clearer understanding of what the Bible says. But by bringing up an interchurch debate, McCracken is forced to choose a side between two Christian views. From his perspective, it is his cessationist view that requires him to open up, be more accepting and let go of certain standards. But what if the cessationist is operating from a true biblical principle—is it right to ask him to compromise his views? Likewise, is it fair to ask Pentecostals to dilute their views in any way if they truly hold their position from a biblical basis? Whatever view of the gifts one may have, it is not helpful to the debate to simply see them as personal preferences and not biblically-based perspectives. The same framework issue arises again in Chapter Ten, where McCracken discusses worship preferences.

Chapter Six does bring up a real issue that makes many Christians, across different denominations and backgrounds, feel uncomfortable. Christians do disagree with each other on fundamental issues—this has been the case for thousands of years and will continue to be the case until Jesus Christ returns. McCracken alludes to this in his other chapters, but ultimately, sin blinds Christians from accurately seeing certain biblical truths. So how does one figure out who is correct? It’s beyond the scope of McCracken’s book to lay out the intricate nuances of correct biblical hermeneutics, so there is a danger in taking his framework too far and applying it to any situation that may cause a Christian discomfort in some form.

The strength of Uncomfortable comes from McCracken’s honesty—it is bold and refreshing. He reminds the Christian that exposing sin can be quite uncomfortable but it is necessary as he or she pursues the faith. He reminds us of the timeless truth that the church consists of all God’s people with all their mess and beauty. Uncomfortable is a good reminder that the process of sanctification will not always feel comfortable, and that is okay—it is part of the journey that God has set for His people for their good until they reach their ultimate home with Him.

Jeffrey Choi graduated from the University of California at Irvine and Westminster Seminary California, and currently serves as the Associate Pastor of Astoria Community Church in Queens, New York.