“I wished people understood the realities of what life was like for a survivor. What it was like to try to bring justice. What it felt like whenever someone asked—or even insinuated—‘Why didn’t you report?’”

Rachael Denhollander

Last year my in-laws came to Canada for the summer, and we passed one humid evening watching Gone Girl. I don’t recommend it. Artistically, it was well done—the suspense was knuckle-breaking and the plot twists were fantastic—but it felt more like an incredibly macabre trainwreck that I couldn’t look away from rather than an incisive examination into the dynamics between men, women, and how public perception shapes individual character. Take Rosamund Pike’s character, Amy—she’s a bright, beautiful young woman who (serious spoiler alert) exploits her husband Nick’s (Ben Affleck) infidelity to make it seem like he’s murdered her for her life-insurance money. When her money is stolen, she seduces, manipulates, and murders an old boyfriend to make it seem like she was kidnapped and held hostage until managing to escape. Her husband and the local authorities figure out what she’s doing, but not until it’s too late, and the film ends with her entrapping her husband into the twisted ‘happy-ending’ narrative she’s orchestrated.

At the end of the movie, I thought of something Tom Hanks said in the romcom classic Sleepless in Seattle when his son, Jonah, urges him to go to New York to meet a woman who’s written him a letter. “There is no way we are going on a plane to meet some woman who could be a crazy sick lunatic. Didn’t you see Fatal Attraction!?” Hanks asks Jonah. “You wouldn’t let me!” his son answers. “Well I saw it! And it scared me to death; it scared every man in America!”

In 2017 (about three years after Gone Girl’s release), the New York Times’ exposé on Harvey Weinstein launched both the #metoo and #churchtoo movements, demonstrating that while women like Alex Forrest (Glenn Close’s character in Fatal Attraction) and Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike in Gone Girl) may certainly exist, they’re not quite as common as men like Harvey Weinstein. Nonetheless, the fear surrounding predatory women exists, and, in the face of an accusation of sexual assault, is the generally first line of defense presented by the accused. It’s a fine and frightening line to walk—it seems like all it takes is one woman to say, ‘He did this to me,’ and the domestic and professional life of the accused is utterly destroyed. On the other hand, few instances of sexual assault take place in the presence of a witness, and even if the victim reports it and submits to a rape kit, it could be months or years (if ever) before her assailant is brought to justice. We’re naturally inclined to be protective of those who have served the community and the church with honor and distinction, but we’re also more aware than ever of the reality of sexual assault and mistreatment as a frighteningly-common experience for many women. How do we support and assist victims while upholding the law that presumes innocence until there’s proof of guilt?

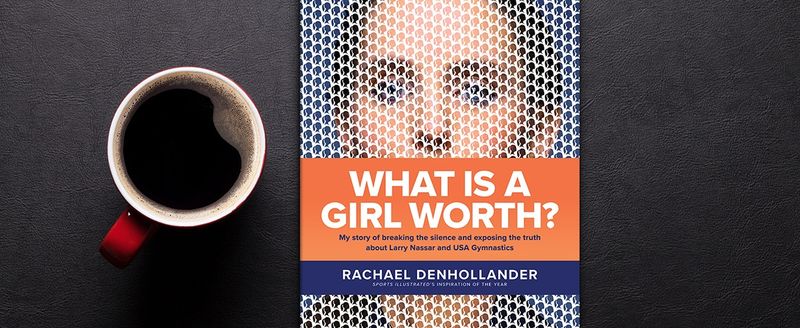

After years of advocating for sexual assault victims, Rachael Denhollander knows that this is generally the first question in the minds of concerned citizens, and it’s this underlying concern that permeates What Is A Girl Worth?, the account of how she was assaulted by Larry Nassar, and the events that led to her public accusation of him in 2016.

Beginning with the story of her happy, stable childhood as the middle child in a Christian homeschooling family in Michigan, Denhollander recounts the way her instinct to protect the vulnerable and defenseless was nurtured by her parents, her burgeoning interest in gymnastics, and the skillful care and support given by multiple positive male figures in her life. She approaches the time of her sexual assault with candor and nuance, carefully describing the various factors that made it possible for Nassar to assault her not once, but multiple times over two years, all in the presence of her mother. She describes in excruciating detail not only her deliberations about whether or not to speak up and the subsequent consequences for speaking up, but the effect this has on herself, her family, and her relationships. The events leading up to her testimony in the Lansing courthouse and the subsequent conviction of Larry Nassar are painstakingly recorded (complete with names and dates), with Denhollander’s motives for all of her actions clearly laid out. The reader is given a firsthand account of how law-enforcement (both municipal and university) handled these cases, how the journalists and media treated her and the other women who came forward, her church’s response, and the public’s reaction. The mental and emotional drain that results is profound. What staggered me was not just the obstacles that were placed in her way, but the fact that these were obstacles placed before a well-educated, upper-middle-class, no-rap-sheet upstanding-citizen attorney. She told one of the head coaches at the gym, who told her that it would be better if she didn’t talk about it. Her church offered little to no support; the university where Nassar worked dismissed accusations that were made as early as 1997.

The problem that emerges from Denhollander’s account is not just that of a lascivious man preying on innocent girls. One of the greatest myths that seems to persist about sexual predators is that they’re rare, one-in-a-thousand genetic aberrations; products of a violent community, broken home and demoralized society that pop up occasionally and are easily caught and incarcerated. Some are, yes, but they’re just as often the well-liked, well-respected upstanding citizens who leverage their popularity and power to gain control over their victim and exploit the confidence and respect they command for the sake of their own gratification. Jimmy Hinton was a pastor. Harvey Weinstein was a well-respected producer. Larry Nassar was a trusted doctor. Louis C. K. was a beloved comedian. Bill Cosby was America’s Dad. These were—are—not Gollumish incels who spend too much time on 8chan; they are (were) leaders in the church, entertainment and medicine.

There is also the wider, more systemic problem of victims not being listened to or taken seriously. “Tears are attacked; no tears are attacked. Too much education and you’re smart enough to manipulate, yet victims from marginalized communities are often written off as ‘those kinds of people’ who are just looking for attention or a quick buck. Every look, every word, every mannerism, every alleged fact could and likely would be scrutinized and attacked, weaponized and used to try to discredit me.” (157-158) Of course, there is a reason for this. The presumption of the innocence of the accused is (rightly) a cornerstone of American jurisprudence—one cannot simply walk into a police station, denounce one’s father / husband / brother / pastor, and expect him to be tossed into prison within the hour. Denhollander has no interest in changing the law in this regard. Part of what makes hers such a compelling voice is the integrity with which she presents both sides of this topic—she understands the cultural instinct to disbelieve and discredit victims. No one wants to believe that someone so well-beloved, so highly respected and talented is capable of something so heinous as the sexual assault of a child. The cognitive dissonance that results when we’re faced with a very terrible accusation against someone we have loved and trusted is so strong that we instinctively react against the person who speaks against him / her. This makes sense—it’s not just the victim that has been violated, our confidence in the accused has been violated, as well. Our own vulnerability and susceptibility is exposed, our security in our community is shaken to its core, and the nameless fears we have for our own children suddenly take a hideous and malevolent form.

Denhollander doesn’t want to see the Napoleonic Code instated or all men everywhere put in sensitivity training—what she wants is for accusers to be given sufficient benefit of the doubt to be listened to, for police reports to be filed, rape kits to be immediately tested, and the accused to be appropriately investigated. Not only did she have to persuade people to listen to her by speaking up repeatedly over the course of several years, she had to teach them about the actual medical technique Nassar purported to be using during his assault, when and how that procedure is actually to be used, the correct legal classification of her case, and how to argue it, all while raising three young children with a husband working toward his Ph.D. Even then, the cultural instinct was to treat her claims with extreme skepticism: “Whereas every statement I made to the press was carefully presented as an ‘allegation’ and run by Larry’s team for their response before publication, everything Shannon [Nassar’s attorney] said was presented as the unvarnished truth—no qualifiers needed.” (279)

In an interview with Sports Illustrated, the question of why Denhollander waited sixteen years before reporting Larry Nassar publicly came up—she responded:

“I regret that I had to wait that long. That’s the way I would phrase it. It had to be the right dynamics in order for it to work, because what we know now—and what I was confident of at the time—is that there were women speaking up. There were children describing exactly what he was doing, and over and over and over again they were silenced. I deeply regret that I and all of these women were in a position where we could not speak up, and we could not be heard. Look what it took to get a pedophile abuser who had abused hundreds of children to be seen for what he was. There were about five different law enforcement agencies involved in investigating Larry. Only one of them handled it the right way. Only one detective did the right thing. Only one prosecutor was willing to pursue justice.”[1]

Coming alongside sexual abuse survivors is not easy—it requires patience, love, and a willingness to shoulder the heavy burden of trauma and grief—but it becomes twice as difficult when we see how it obligates us to examine how we (both as a church and as a society) can unconsciously foster a culture that enables and protects abusers. By clearly, carefully and charitably retelling what was unquestionably the most horrific and agonizing period of her life, Rachael Denhollander has not just made it possible for present and future victims to speak, she has given the church the tools they need to better understand the nature of abuse, the toll it exacts on its victims and their loved ones, and the categories with which to better process the assumptions and beliefs we all hold about the worth of women and men.

Brooke Ventura is a writer. She lives in Ontario, Canada with her family.

[1] httops://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UEyZzcOMSJQ, accessed 7 January 2020