Historic Reformed theology, as it was conceived and developed in the early modern period, offers a conceptual depth that continues to captivate scholars and students alike. The tradition’s philosophical sophistication can be seen most prominently in the tradition of Reformed scholasticism, as it offers a robust and nuanced philosophical framework for exploring key theological concepts, such as the nature of God, the relationship between faith and reason, and many other moral topics involving law, actions, and virtues.

Moreover, the intellectual legacy of Reformed scholasticism has enabled students to grasp the nuances of Reformed thought that had been elusive in many modern discourses. The study of the field requires a deep engagement with a rich intellectual tradition that spans centuries, and by immersing themselves in this tradition, students could develop a profound understanding of the theological issues at stake and the ways in which Reformed theologians in the past sought to address them. This, in turn, can equip students to make more informed contributions to ongoing debates within the field of theology, and guide contemporary conversations toward historic and orthodox ideas.

One philosophical tradition worthy of note, within the scholastic streams of Reformed thought, is termed “realism.” Philosopher Alessandro D. Conti stated this about medieval philosophy in general: “Realism and nominalism were the two major theoretical alternatives in the later Middle Ages concerning the reality of general objects: realists believed in the extramental existence of common natures or essences; nominalists did not.”[1]

There isn’t enough space here to discuss both traditions, in introducing the breadth of scholastic thought, but something about realism can still be said by way of introduction, as it was a dominant position adopted and appropriated by many Reformed thinkers of the Reformation period. Therefore, we will first cover some basic issues concerning the intelligibility of the world, and then, rather swiftly, move to three distinguishable traditions within the school of realism, laying them out in short and simple terms.

The Intelligibility of the World: Basic Issues

Suppose that you wished to analyse the order of human cognition. You would acknowledge that there are at least two kinds of things that humans can know with their minds: extramental and intramental. First, you would analyse the way humans come to know extramental objects, that is, the things that exist outside of the human mind. Knowing the nature of apples is an example: many people throughout human history have devoted much attention to the knowledge of apples, and their discoveries have been important not only for farmers but also for doctors who now recommend apples as part of a healthy diet. Knowing the nature of chickens is important too, again not only for farmers but also for athletes, as the protein richly concentrated in chicken meat is important in building up human muscles. But how did humans come to know that chicken is rich in proteins? And how did we learn that apples are healthy fruits that can keep doctors away if consumed regularly? It is simply because humans have devoted much time and effort to knowing and understanding their natures. So, these objects that exist outside of the human mind can be treated as extramental in philosophical terms, but all humans naturally and intuitively occupy themselves with this kind of cognition for a better grasp of the surrounding world, or of the things that interest them.

Then there is another kind of object that humans can know and understand. These are called intramental objects, because human reason can also analyse concepts that are in the mind. Humans not only explore the outer world and analyse their discoveries—whether they be chickens or apples—they also discover the inner world of human souls and delve into the concepts that they find there. What is “love,” which humans always talk about? What is “justice”? And what is “happiness”? This kind of cognition is often professionally pursued by philosophers at very abstract levels, but this does not mean that ordinary people don’t get to know them: people always try to understand the ideas, meanings, and intentions involved in human communication, and that is a universal phenomenon of human life that gets manifested in all kinds of cultures. People are always trying to say something to communicate ideas or concepts, and all by nature are inclined to listen to them, to analyse them, and to understand them.

Let’s then come back to the issues of realism. What are the relationships between these extramental and intramental objects? Can the human mind really know the true essence of things that exist outside of it? Can it really know the common and individual features that define things? If so, can the human mind also know the deep meaning of concepts, ideas, or thoughts themselves? Are things like justice, love, and happiness mere concepts that do not really exist in reality, or are they real features of the world that reason comes to recognize? No doubt, these questions do not exhaust all the discussions involved in scholastic philosophy, but they nonetheless capture some of the enquiries that were actively pursued in the Western world for a long time, and these types of questions were in the background when many philosophers, including many theologians, thought about the relationship between God and the created order.

Platonic Realism

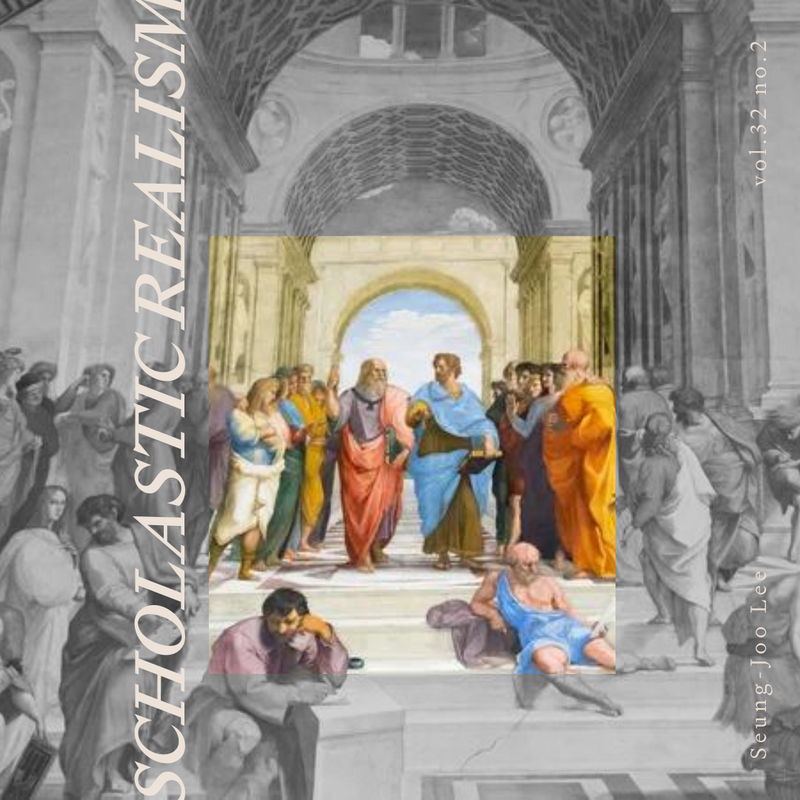

Now, the first stream of realism can be called Platonic realism. To simplify things, a distinctive characteristic of this position is that the essences of all things are located neither in the things themselves (in re) or inside the human mind (in intellectu), but in the third realm called “the world of the Forms.” This gets at the famous Platonic Form that functions as the ultimate rationale of all things that exist and move in this world. So the very essence of all animals called “animality” is located neither in the animals themselves nor in the human mind that knows it, but in the third realm that transcends all material and mental domains. In other words, the whole world that we live in is connected to this third world for all its existence, operation, and movement, and anything in this sensible sphere is a reflection of or participation in those Forms. That is why, if you looked at Raphael’s famous painting, “The School of Athens,” Plato’s finger would direct you to gaze upward to understand the essence of all things.

Aristotelian Realism

The second school within realism, again to simplify things, is Aristotelian realism. Aristotle saw that Platonic realism had some problems. First of all, if the essences of things in the world are not located in themselves, then all things would have very blurry and weak systems of existence. For instance, if what you really want to know is the “appleness” of apples, then you would look beyond or above the existent apples to grasp it, and you have legitimate reasons to neglect actual apples or to bypass them as they are not the real sources of their nature. The same applies to chickens: if they are mere reflections of and participants in the invisible Form called “chickenness,” the existent chickens would lack a robust system of existence since their common essence is so detached from them. Secondly, the Platonic Forms would lack robust systems of causes, and that is one of the reasons why theories of causation were developed rigorously in the Aristotelian tradition. For one thing, in Platonic realism it is unclear how the Forms would cause things to come into existence in this current world, and thus the order of interactions between “that” third world and “this” present world lacks precise definitions. Do the Forms themselves have the causal powers to actualize things into existence, or are they inert? If they are inert, then how do actual existents come to participate in their transcendent Forms? Should we refer to the “Fourth” world to explain the activities of the “Third” world?

So Aristotelian realism made the point that a thing’s essence is discovered in the thing itself, and it can be abstracted and conceived by human reason. There is no pressure to look up to a third world, and there is no need to neglect the present order to know the essence of things. Things move and actualize each other in this present realm, following a certain causal pattern, and as such the philosophical explanation of the world can justifiably concentrate on the observable phenomena that humans can know, understand, and grasp here and now. This is why Aristotle points his palm downward, to orient people to the things that are down here, in the painting mentioned above, “The School of Athens.”

Scholastic Realism

Lastly, there is a third kind of realism called Scholastic realism. This tradition of thought was developed in the medieval period and later reached its high point in seventeenth-century Europe. The genius of this position, developed by many Christian thinkers, was to work with both Platonic and Aristotelian traditions in the light of theological truths. Edward Feser, a Roman Catholic philosopher, explains:

Like Aristotelian realism, Scholastic realism affirms that universals exist only either in the things that instantiate them, or in intellects which entertain them. It agrees that there is no Platonic ‘third realm’ independent both of the material world and of all intellects. However, the Scholastic realist agrees with the Platonist that there must be some realm distinct from the material world and from human and other finite intellects. In particular—and endorsing a thesis famously associated with Saint Augustine—it holds that universals, propositions, mathematical and logical truths, and necessities and possibilities exist in an infinite, eternal, divine intellect.[2]

So, in Scholastic realism, both Platonic and Aristotelian ideas are put together in systematic ways, but they are refined, reformed, and revised according to the theological truths grounded in the sacred Scripture. It does account for the intricate nexus of causal orders that move creaturely things into existence, but it also explains how all things in creation are related to the transcendent being, intellect, and will. In this regard Augustine is recognized as a brilliant thinker who advanced much of the discussion on these issues, and that is one of the reasons why many of the heated debates in the Reformation period revolved around understanding and claiming Augustine’s intellectual legacy. Remember Calvin’s famous statement, “Augustinus totus noster est (Augustine is totally ours).”

Conclusion

Now, it just needs to be said that these philosophical ideas are important for understanding many of the philosophical assumptions and contentions in Reformed scholastic theology. One example is Franciscus Junius (1545–1602) who stated, in rather simple terms, “the underlying structure of the things which exist is twofold: for some exist in re, others in intellectu.”[3] Although we cannot go deep into Junius’s thought now, the statement itself is an indication that the dynamics between extramental and intramental domains of reality occupied an important place in theological study, and that these were used to understand the metaphysical order of the world in relation to God and to us as humans. And, once we have carefully analysed his ideas as a whole, it is safe to conclude that the structure of reality in Junius’s thought is characterized by a web of causal interactions between divine actio (action) and human ratio (reason) in a stable ordo (order), and it reflects a form of Scholastic realism that was developed through the medieval period. Therefore, to better understand historic Reformed thought, knowing something about Scholastic realism is greatly beneficial, and it will no doubt yield enjoyable opportunities to learn about the deeper layers of the created world. And that, of course, both in philosophical and theological terms, and according to faith and reason.

Dr. Seung-Joo Lee (PhD, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) is Pastoral Assistant at Knox Presbyterian Church of Eastern Australia and Adjunct Lecturer in Theology at Presbyterian Theological College, Melbourne.

[1]. Alessandro D. Conti, “Realism,” in The Cambridge History of Medieval Philosophy, vol. 2, revised edition (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 647.

[2]. Edward Feser, Five Proofs of the Existence of God, 102.

[3]. Franciscus Junius, Treatise on True Theology, 184.