Questions of human identity are shaking societies to their very core. In her book Primal Screams, Mary Eberstadt explains how traditional answers to this question found in family, community, and faith identity have in large part disintegrated. She writes, “Every one of the assumptions [we] could take for granted is now negotiable. No wonder erotic leanings and ethnic claims have become substitute answers to that eternal question, Who am I?” (39). Reflecting on this primal question and the ongoing search for identity in countless constructed categories and endless intersectional identities, I am reminded of the ancient martyr accounts. As waves of persecution tested the early church, the martyrs frequently made a confession of definitive and consummate identity with the Latin phrase, Christianus sum. A simple phrase to be sure, but one worth elucidating. What exactly were the martyrs confessing with this phrase? Does our English translation of “I am a Christian” really capture it fully? What can this phrase teach us about identity?

In Latin, Christianus sum, is how you would communicate either “I am a Christian,” or “I am Christian.” In English, we tend to use the indefinite article “a” when referring to ourselves as Christians and in translating this phrase. But in our age of the sovereign self, I wonder if it really captures the depth of Christian identity, or even worse, might bring with it unintended overtones of autonomy and individuation. Perhaps the English “I am a Christian” and the Latin Christianus sum are both suggestive, but in opposite directions—the English towards an individual identity-choice, the Latin towards something deeper, more primal.

Christianus Sum and Ultimate Identity

In his analysis of early martyr accounts, William Weinrich explains that when the martyrs confessed Christianus sum, it “was not merely to state that one believed so-and-so to be true. It was a claim of personal identity that re-ordered one’s basic social, familial and political allegiances” (11). Even the blessings of family identity sometimes gave way to the even more foundational identity in Christ.

This is illustrated well in the martyrdom of Perpetua, a young noblewoman, with an infant still being nursed. Weinrich recounts how Perpetua’s father “begs her not to dishonor her family and bring upon it ill-repute and social disgrace” with even the Roman governor urging her “to take pity upon her father and infant.” Yet when asked, “Are you Christian?” Perpetua still replied, “Christiana sum.” Weinrich explains, “The claim to Christian identity bears within itself the claim that all family ties and associations and obligations are temporal, penultimate and may not assume our deepest loyalties” (12).

Perhaps to capture the essence of it, we might say, that early Christians understood their identity as Christic, or Christ-ian. This identity, Jonathan Linebaugh notes, “is not determined by what they have inherited or achieved – not by biology or biography, by pedigree or performance – but by God’s gift of Jesus Christ” (97). Yet, there is also an inherent tension in this identity: the sinner and the saint, the old man and the new. The life of the Christian thus follows the cruciform pattern of death and resurrection, putting to death the old man and rising to new life—“dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 6:11). This cruciformity is re-enacted in baptism (cf. Rom. 6), daily repentance, and surely also in the martyrs’ death. For the early church there was a deep resonance between baptism and martyrdom.

The death and life, now-and-not-yet, of Christian identity will be resolved fully in the New Creation. This makes the identity of “Christian” ultimate, eschatological even, driving towards the telos of the universe in the wedding of the Lamb and his Bride. Such conjugal imagery reflects a deep, core identity, the destiny towards which the Christian marches.

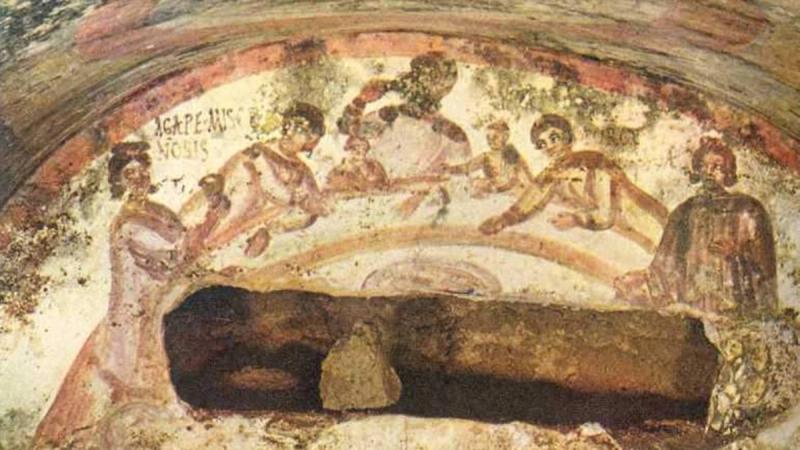

Christianus Sum, Eucharist and Communal Identity

The marital symbolism of the wedding feast is in the background of the martyrs’ confession, as seen in the close connection the early church also made between martyrdom and the Eucharist. Each martyr was participating with the Martyr, Christ, which they believed, incorporated them more fully into the Eucharistic meal. In this regard, Revelation 6:9 is intriguing at the very least, where John sees “under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne.” Perhaps the ancients’ desire for martyrdom was extreme, but their understanding of martyrdom’s connection to the Christ-event is worth noting.

This is evident in The Martyrdom of Polycarp, where Polycarp prays, “I give You thanks that You have counted me, worthy of this day and this hour, that I should have a part in the number of Your martyrs, in the cup of your Christ, to the resurrection of eternal life, both of soul and body. …Among whom may I be accepted this day before You as a fat and acceptable sacrifice.” Likewise, as martyrdom nears for Ignatius, he prays in his Epistle to the Romans, “Allow me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ.”

Weinrich captures this well: “To commune with the Body and Blood of Christ was to be bound with Him who was Himself the ‘faithful witness’ (Rev. 1:5)….Participation in the Supper of the Lord, therefore, bears within itself the destiny of martyrdom — should that be according to God’s will and purpose” (10). The martyrs believed that in some way, union with Christ was heightened in their participatory suffering with him.

Perhaps Paul has something similar in mind in Colossians 1:24 where he writes, “I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church.” Of course, nothing lacks in Christ’s work of salvation; it is complete and full. But communicating that salvific work to the world, frequently calls forth an embodiment of Christ’s suffering in the lives of Christians. Christians not only take up his name, they take up his cross as well. Paul Kretzmann explains, “The sufferings of Paul advanced the whole interest of the Church of Christ, the whole body receiving benefit from that of one member,” which “makes the Christian fellowship more intimate” (324).

Individual and communal identity find their nexus in the sacramental eating of Christ, where we participate together in the holy meal with our bodies, words, deeds, and eventually through death, whether a martyr’s death, or not.

Christianus Sum, I am Christian

The elemental identity and unity with Christ communicated in the phrase Christianus sum, seems to be something more than what comes across in our everyday usage of “I am a Christian.” My fear is that in our current milieu, the “a” unintentionally suggests a segmented, or atomistic faith, with each individual making their individual choice to be “a” Christian. This also could make it easier to relegate one’s faith identity to a secondary position, as just another identity-category among many that make up your “true self.” Alan Noble writes, “I may try on Christianity like I try on styles of clothes or beliefs, but the ultimate focus…is not on an external being who loves me but my own search for fullness” (59-60). He further explains, “our identity and our ability to choose its features becomes the basis for our being in the world, rather than some outside authority. So that even when we believe in God’s existence and choose to follow him, we do so because of an inner decision” (44).

This individualist approach seems to run counter to the ancient mindset. As Weinrich notes, “Christian martyrdom was not an act of heroism that was personal and individual. It was an essentially public act that called into question any ultimate, transcendent attachment to that which was not God” (11). He goes on to say, “This is why martyrdom must be regarded as a fundamentally ecclesial act” (11). Martyrdom was not an autonomous act; it occurred in the context of the Christian community. It was an identification not only with Christ, but also with his living body, the Church that heralds his name to the world.

In an age where questions of identity are both so central and so confusing, we have an eternal anchor for identity that is more stable and lasting than our shifting interior lives, or our best exterior efforts. The early martyrs’ confession of Christianus sum reminds us of this fact, bringing questions of identity beyond individual choices or lived experience, beyond personal achievement or social status, beyond racial categorization or sexual preference.

The question of Who am I? remains essential, as the frantic search for meaningful identity on full display today reveals. The tendency to find our identity in our own experience and achievements contrasts with the martyrs, who in confessing Christianus sum, found their ultimate identity not in their name or their history but in the name and the history of Jesus Christ, which became theirs through Word and Sacrament. By means of this union with Christ, their identity was sure and firm, enabling them to face the sting of death, knowing that what awaited them in the Eschaton would be the fullest expression of human identity imaginable: a glorified humanity in full communion with the Trinity and with each other.

Joshua Pauling teaches high school history, was educated at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. In addition to Modern Reformation, Josh has written for Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, Salvo Magazine, and The Imaginative Conservative. He is also head elder at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, North Carolina.