Long before Twitter, YouTube, or Facebook, C. S. Lewis understood where cancel culture led. In The Great Divorce, his fictional depiction of heaven and hell, Lewis paints a picture of serial conflict that leads to further and further isolation in the cities of hell. Lewis had no way of knowing how accurate his description would be regarding our current culture.

Moving Away From One Another

While traveling on a bus going from Lewis’s creative depiction of hell for a visit to heaven, the main character gets into the following conversation with a long-time inhabitant of the hellish city:

“The parts of it that I saw were so empty. Was there once a much larger population?”

“Not at all,” said my neighbor. “The trouble is that they’re so quarrelsome. As soon as anyone arrives he settles in some street. Before he’s been there twenty-four hours he quarrels with his neighbor. Before the week is over he’s quarrelled so badly that he decides to move. Very likely he finds the next street empty because all the people there have quarrelled with their neighbors—and moved. So he settles in…He’s sure to have another quarrel pretty soon and then he’ll move on again…

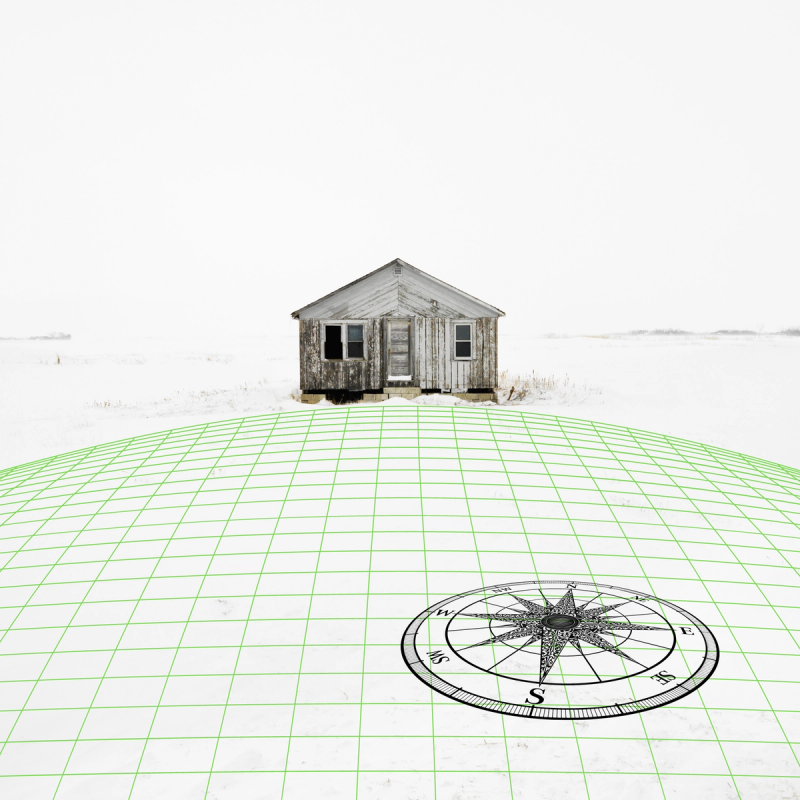

“They’ve been moving on and on. Getting further apart….Millions of miles away from us and from one another.”

While we do not have a physically expansive and inexhaustible place like the hell-town Lewis described, we do have the internet. This technology, which does have its positive contributions and capacities, provides a seemingly inexhaustible, albeit two-dimensional, way to separate ourselves from others with whom we disagree or whom we greatly dislike.

Algorithms are not ultimately to blame, though they certainly stoke the flames of our sinful desire to separate and isolate. Left to ourselves in our fallen state and captive as humanity is to the prince of this age, we tend toward isolation when hurt, misunderstood, or misaligned with others (2 Cor. 4:4). When Paul was contrasting the works of the Spirit with the works of the flesh in his letter to the Galatians, he included “enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, and divisions” among sorcery, orgies, and drunkenness as evidence of the flesh (Gal. 4:20–21).

The Enemy stokes divisions and dissensions, while the Spirit promotes unity and harmony. There is, of course, a command to be separate from evildoers and to separate the immoral brother; however, even then, such actions are to stem from a deep desire to see the parties with whom we are in conflict (over clear Scriptural commands) brought to full repentance and restoration (2 Tim. 2:24–26).

The Scriptures have much to say about the dangers of being quarrelsome and quick-to-separate. When people hurt us (which they most certainly will) or when we disagree with a brother or sister on matters of political opinion or conscience (which most assuredly happens on the daily), it is our flesh’s knee-jerk response to want to create distance from them. Distance breeds further distrust and miscommunication. As such, it is easy to recreate, at least in our hearts, Lewis’s description of astronomical distances.

Getting Underneath Cancel Culture

Even if you do not find yourself deleting friends and hiding their posts for months at a time, you may be surprised to find the seeds of cancel culture within you. Since the moments after the Fall, humans have struggled with self-justification, which is the seedbed of cancel culture. Adam and Eve immediately began pointing to the other as the problem, rather than owning their sinful mutiny against God (Gen. 3:8–13). Cain felt justified in bringing his own offering to God, refusing to come by way of sacrifice (Gen. 4:1–8). Even though our technology has changed drastically since then, the tendencies of our hearts have remained sadly the same. Even on the other side of the cross of Christ, our hearts stray toward self-justification which nullifies and empties the costly grace of God (Gal. 2:19–21).

It’s far easier to draw the lines between good and bad out there in culture than in here, within the confines of my own heart. As Alexander Solzhenitsyn humbly recognized from the cauldron of cancel culture that was the Russian regime, the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. As he sat in prison, cancelled because of his activities and beliefs, he realized that cancelling the “enemy” did not solve the problem. The problem lies much closer to home.

When I run a magnifying glass over my heart motives, I find a disturbing trend toward cancel culture in my thoughts. Sure, I know and proudly proclaim publicly that Christ is both just and justifier of the one who has faith in Christ (Rom. 3:23). However, I draw (and redraw) subtle lines of self-justification around those who look, think, and act like me. While I would never verbalize it or dare to digitally cancel brothers and sisters in Christ, I distance myself from those who don’t adhere to my particular formula of Christ plus: Christ plus evangelism in my method, Christ plus my particular political leaning, Christ plus my denomination. Notice the ubiquitous my in the former statements.

The constant narrowing of our circles to shore up a sense of our own self-justification might feel like security; however, it results in a shrinking formational community that bleaches the variegated grace of God (1 Pet. 4:10). In self-justification, I subtly hem myself into a circle of safety that looks more and more like me and less and less like the multicultural (and thus multi-perspectival) community of which the Scriptures speak (Rev. 7: 9–10).

When we begin to move away from those who do not look like us, act like us, or think like us (whether on a computer or in a community), we would do well to pray David’s searching prayer: “Search me, O God, and know my heart! Try me and know my thoughts! And see if there be any grievous way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting!” (Ps. 139: 23–24).

Moving In, Not Away

This side of glory, community will always be a mixed bag. We will love one another deeply. We will also just as deeply hurt one another. We will sing the praises of Christ in our churches on Sunday and singe each other on Monday. Apart from the binding, humbling, convicting work of the Holy Spirit, we have no hope.

But Christ did not leave us alone; he equipped us with the Third Person of the Trinity (John 14:15–18). The Holy Spirit delights to illuminate the Scriptures to us; he has full access to the dark recesses of our hearts; and he loves to point us individually and collectively to Christ. With the Spirit and the word, we stand a chance to fight the clarion call of cancel culture. With him, the discomforts of disagreements and disappointments can serve to press us more deeply into the gospel. Rather than moving out and away, we can lean into Christ.

Rather than making the other our enemy, the Spirit helps us remember the enemy of our souls (Eph. 6:12). Rather than pointing out the speck in our neighbor’s eye, the Spirit will help us face the log in our own (Matt. 7:1–5). Rather than focusing on our enemies, the Spirit will remind us that we once stood as enemies of the cross (Rom. 8:7–9). If God has closed the eternal breach between us and him, he can help us to close much smaller distances between us and those with whom we disagree on secondary or tertiary matters.

Disagreements compel us to move. By the power of the Spirit, we have choices to make. Will we move away from one another following the lead of cancel culture? Or will we move towards deeper dependence upon God who calls us to biblically and sacrificially love those with whom we do not see eye to eye. Our daily decisions and interactions with others are helping us toward one of two ends: isolation in the echo chambers of our self-justification or community centered on justification in Christ.

Aimee Joseph has spent many years directing women’s discipleship and ministry at Redeemer Presbyterian Church and in Campus Outreach San Diego. She is the wife to G’Joe who has recently planted Center City Church, and mother to three growing boys. Her first book, Demystifying Decision Making released with Crossway in January 2022. You can read more of her writing at aimeejoseph.blog.