The early chapters of Genesis have always been of extraordinary interest to the people of God. Attempts to plumb the depths of the origin accounts became a particular preoccupation in the commentaries, homilies, and letters of the Patristics. Augustine, inheriting this tradition, famously attempted an explanation of the Genesis creation account no less than five times.

One of those attempts is recorded in the latter part of his Confessions (the part that few people read!), written at the very end of the fourth century. In book XII, he begins his reflections on the early chapters of Genesis with these words:

My heart, O Lord, affected by the words of Your Holy Scripture, is much busied in this poverty of my life; and therefore, for the most part, is the want of human intelligence copious in language, because inquiry speaks more than discovery, and because demanding is longer than obtaining, and the hand that knocks is more active than the hand that receives.

He knew, as many had found before him and many more have found since, that mining the treasures of the Genesis account of creation requires patient and persevering work on our part, and, most importantly, enlightening grace on the part of God.

A little later in that book, in one of his customary prayerful interjections, he picks that theme back up, yet in a striking way:

Oh, let truth, the light of my heart, not my own darkness, speak unto me! I have descended into shadows and am darkened, but from this place, even from this place, my love was directed toward you. . . . Let me not be my own life; the life I have lived of myself has been death to me: in you I revive. Speak to me; converse with me. I have believed your books, and their words are very deep.

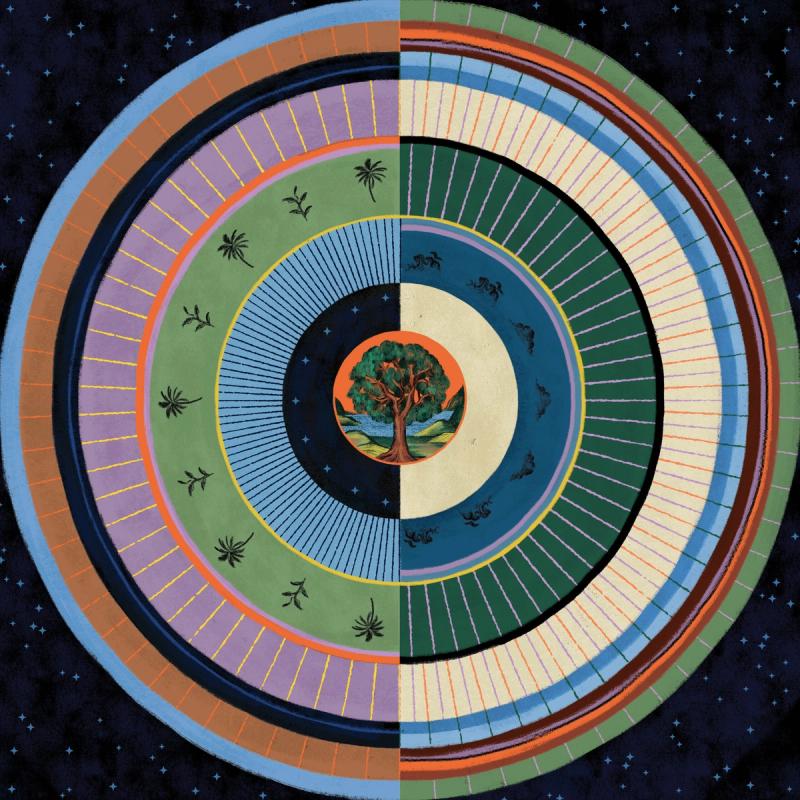

Augustine here pictures the books of God (nature and Scripture) as something like the original state of creation, profoundly deep and full of potential. Surrounding this deep is the darkness of the human mind, unable by its own powers to penetrate the depths. If these books are to fulfill their potential—that is, ordering all toward the enjoyment of God’s rest—then God must speak, “Let there be light.” Augustine sees in these beginning chapters of Genesis a metaphor useful for prayer: that God would sanctify his mind—that process whereby the human mind, clouded in finite ignorance and bent over in sin, is enlightened, straightened, and directed by God back to God.

Nor is this a wayward or insignificant lesson to take from Genesis. Indeed, it is a lesson that the apostle Paul himself draws: “For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6). May we approach Scripture with eyes ready to seek and hands ready to knock. And may God grant us light to see into its depths.

Joshua Schendel is the executive editor of Modern Reformation.