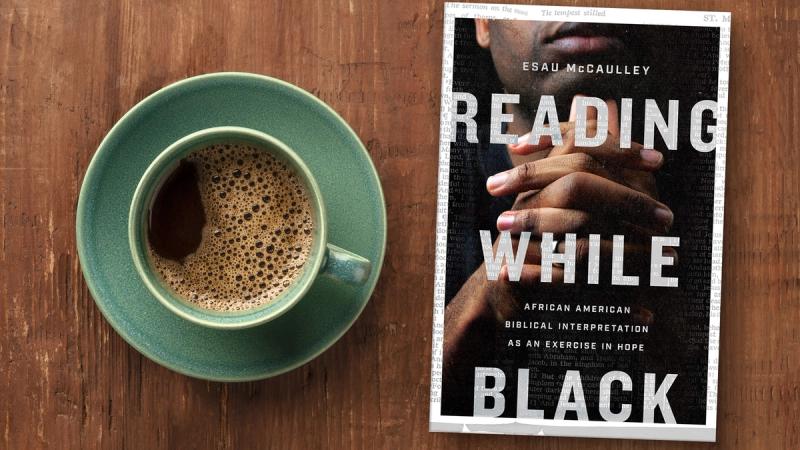

The Pastoral Heart of Reading While Black

The title for Esau McCaulley’s book, Reading While Black, is a play on Driving While Black, a sardonic description of racial profiling on America’s roads. Recent research confirms African American anecdotes. By his reckoning, McCaulley has been “stopped somewhere between seven and ten times on the road or for existing in public spaces for no crime other than being Black” (28). There is no bitterness in McCaulley’s writing. Instead, he yields from these experiences the “question of how the police treats its citizens” and recognizes this to be “a pressing issue in the lives of Black people” (28). As a Black Christian, McCaulley has special motivation to ask certain questions of Scripture. He implies that this is a motivation other biblical scholars lack, given the scarcity of treatment on the question of policing in works of New Testament ethics, particularly as it concerns Romans 13:1–2: “Is the guild correct? Is the issue of the state’s treatment of its citizens a subject foreign to the New Testament such that Black folk looking to these texts will find little succor?” (28). McCaulley thinks not.

Seven slim chapters and a conclusion each, in their turn, engage a topic of special interest to African Americans. Essay-like, what unifies them is not, à la Cone, a hermeneutical principle that distinguishes McCaulley’s exegesis as “Black.” In fact, his exegesis, in itself, is not controversial. What makes it “Black” is instead the special concerns that he, as an African American, brings to the text. This book treats the sort of subjects and verses you would hear preached about regularly at a Black church, though not so much at a white church—not, McCaulley strongly implies, because whites read less faithfully or less rigorously, but simply because they have a different set of pastoral concerns. We drive the same roads and observe the same laws, but our experience on those roads differs.

The “Black” Bible

The Bible has always held a central place in African-American Christianity. Despite this affection for the Bible, in 1969 no more than six African Americans held doctorates in Old or New Testament.[1] Those few welcoming seminaries tended to be progressive and did not share the Black church’s historic view of the authoritative status of the Bible which McCaulley, and many other African Americans, grew up knowing. McCaulley explains:

We [members of the Black ecclesial tradition] are thrust into the middle of a battle between white progressives and white evangelicals, feeling alienated in different ways from both. When we turn our eyes to our African American progressive sisters and brothers, we nod our head in agreement on many issues. Other times we experience a strange feeling of dissonance, one of being at home and away from home. (5)

For McCaulley, Black ecclesial theology stands apart from other voices and finds its home in a long history of Black community and preaching. “For a variety of reasons,” McCaulley explains, “this ecclesial tradition rarely appears in print. It lives in the pulpits, sermon manuscripts, CDs, tape ministries, and videos of the African American Christian tradition” (5). For this reason, McCaulley places the book in the “Black ecclesial tradition,” that is, “the practice of Bible reading and interpretation coming out of the Black church,” rather than what McCaulley calls “mainstream” Black Theology, which developed in progressive seminaries (3, 171). The soul of McCaulley’s work is to introduce and define this Black ecclesial theology, giving us a sampling of a preaching tradition which few outside the Black church have heard.

Locating McCaulley in Black Theology

The reader who wishes to find McCaulley’s location in Black Theology must wait until the end of Reading While Black, in the final chapter, titled “Bonus Track.” For anyone with an interest in Black Theology, this chapter is a must-read and alone worth the price of the book.

By now it should be evident to the reader that there is a distinction between Black Theology and Black Liberation Theology, though the popular level of discourse at the moment uses these interchangeably. Drawing out this distinction is part of the purpose of Reading While Black. Black Theology is rooted in the Black ecclesial tradition—ecclesial as in the practices of gathering, worshipping, and preaching—that goes back to the clandestine worship services of African-American slaves. Liberation Theology, on the other hand, originated in Roman Catholic Latin America in the mid-twentieth century. While these strands, Black Theology and Liberation Theology, were brought together powerfully in the writings of Rev. James Cone, they are neither interchangeable nor identical. Black ecclesial theology is, as it were, parallel to Black Liberation Theology and shares many of its concerns if not always its conclusions, but not all Black Theologians are Liberation Theologians.

McCaulley agrees with Cone at several points. Notably, that God did indeed reveal His character by liberating the Hebrews from Egypt. (Surely, we would take Him to be a different sort of God entirely if He had instead instructed His people to submit meekly to the Egyptians. Thus, God’s choice of enslaved Israel to be His people speaks to us something of His character.) McCaulley takes issue, however, with the first principle of Cone’s hermeneutic. In his essay, “Biblical Revelation and Social Existence,” Cone writes:

The hermeneutical principle for an exegesis of the scriptures is the revelation of God in Christ as the liberator of the oppressed from social oppression and to political struggle, wherein the poor recognize that their fight against poverty and injustice is not only consistent with the gospel but is the gospel of Christ. (174)

While Cone is correct to identify the themes of liberation and justice to the poor are among the most prominent in Scripture, McCaulley thinks Cone goes too far to interpret these in all instances in socio-economic terms: “Is it accurate to claim that political liberation is so much the overriding concern of the Old and New Testaments that we can claim that is it the gospel of Christ?” (178). What’s more, McCaulley thinks this conclusion is out of step with the Black ecclesial tradition. African-American slaves did not see in the Scriptures merely a promise of emancipation: the early evidence indicates that they rejoiced in the salvation of their souls: “It is the totalizing nature of this [Cone’s] claim that…seemed to separate Cone from a significant strand of the Black Christian tradition that combined the transformation of systems with the individual transformation of life” (178).

It is over against mainstream Black Theology that McCaulley defines the features of the Black ecclesial tradition: it is socially located, theological, canonical, and patient. It is socially located in the sense that it cannot ignore the question of what it means to be both Black and Christian. It is theological because it names evil according to its understanding of God’s character. It is canonical because it gives the Bible its central, normative place in all preaching. And it is characterized by patience; patience, that is, as an exegetical virtue; patience that chooses to linger with a passage it finds difficult—like Romans 13:1–2 or 1 Timothy 6:1–3—rather than reject it outright either because it doesn’t understand it or because of a negative experience with it. This is a sort of ecclesial interpretation from which the whole church can learn.

[1] Leon Wright was the first African American to earn a doctorate in New Testament, which he was awarded at Howard University in 1945. See Gayraud S. Wilmore, “Introduction,” in Black Theology: A Documentary History, Volume One: 1966-1979, 155. The history of their exclusion is traced in Jemar Tisby, The Color of Compromise.