However complicated the genealogy of modern morals might be, it seems a sad but unavoidable conclusion that all the nuances and subtleties of thousands of years of ethical reflection on the human condition have culminated in a morality that increasingly operates in terms of two simple categories: love, and its antithesis, hate. Front yards are adorned with signs which declare that ‘Hate has no home here’ in response to some apparent fear that the absence of such might leave anonymous passers-by in doubt. Others trumpet the fact that ‘Love has a home here,’ followed by a traditional litany of the values of middle America: love of home, family, and country. In short, the moral discourse of the nation has been reduced to these two words, love and hate, which are emotive idioms by which we give absolute ethical status to those things of which we either approve or disapprove. The language is such that it preempts discussion and impoverishes the public square: one cannot defend hate or reject love without effectively placing oneself outside of the bounds of civilized society.

And yet there is an obvious problem. In contemporary society, the terms ‘love’ and ‘hate’ may have a certain emotional appeal and may help turn the world from a daunting moral maze into an attractively simple roadmap, but their content is at best fluid and at worst nebulous. They speak more of social tastes than transcendent concepts of right and wrong, good and evil. Their omnipresence in a culture where aesthetics determines ethics presents an obvious challenge (and danger) to Christians seeking to live as faithful citizens of both the kingdom of man and the city of God. Indeed, so many of the debates which routinely erupt in the church—from which Bible translation we should use to whether women should wear this type of clothing or have that kind of job—often have more than an underlying whiff of personal or subcultural taste about them, even as we attempt dress them up in speciously ‘objective’ arguments. ‘The Bible forbids it’ might be code for ‘I don’t like that,’ and ‘The Bible says,’ may just mean, ‘I like this,’ more often than we care to admit.

This is not a new problem. In the early years of the Reformation, Martin Luther was so carried away by his recovery of the doctrine of justification by grace through faith that he believed that little positive moral teaching was necessary in the church: believers would simply spontaneously respond to God’s grace by performing works of love. Luther assumed that Christians would know what such works were, but by the late 1520s, it was clear to him that this was not the case—the church required careful and precise moral guidance; the rhetoric of ‘just do works of love’ was a dictum into which Christians could pour any content and none, as the fancy took them. (This was the primary concern which lay behind his composition of his Small and Large Catechisms.)

The language of love and hate has an intuitive force because of its emotive rhetorical power. It is not language that allows for a bland middle ground; it speaks with passion and certainty but does not, in itself, demand any specific content, just a collection of potent connotations. What content love and hate possess today is provided by the cult of expressive individualism which now grips the popular cultural imagination. You can and should be (almost) anything you want to be, and our moral discourse has adapted to make it very hard to mount any challenge to that. Love has become that which affirms or enables somebody to be who they think they are; hate has become that which hinders the same. It is true that not all individual identities enjoy the legitimacy conferred by the social and cultural consensus: whatever moral debates surround the status of being gay or transgender, it us undeniable that part of the power of the political lobbies which represent such groups lies in the ability to capitalize on the language of victimhood and marginalization, language which carries significant aesthetic weight in modern society. Lest we forget, the right too has its aesthetics which capitalize on what is, at its core, the same commitment to expressive individualism as the left (even though the individualism it promotes is a decidedly different sort than the left’s). The language of ‘rugged individualism,’ terms like ‘maverick’ and slogans such as ‘Make America Great Again!’ have a powerful appeal to the right which, like its counterpoints on the left, is built not on argument but rather on emotions elicited by their aesthetic connotations as it draws on the powerful emotional imagery of America as a nation founded in opposition tyranny, as conquering an untamed and wild frontier, and as victor in the Cold War. Of course, aesthetics does have its limits, even in the amoral anarchy of today’s world—the right to express oneself does not (at the time of writing) entail a right to physically harm those persons who disagree with you, and those who think it does generally face a strong degree of disapprobation in public opinion. Some margins thankfully still remain aesthetically more marginal than others; but this hardly damages the central point, that to make emotional appeals to cultural tastes is a potent political strategy.

We can therefore summarize the modern ethics of love and hate as follows: love and hate are today terms that frequently denote nothing more than the contours of contemporary taste, with all of the cultural and historical arbitrariness which that implies. In using them, we appear to be making objective moral claims but we are in fact merely giving voice to the tastes of time. We might even say that today’s approach to love/hate provides unwitting support to the claims of both the logical positivists and the post-structuralists. The former asserted that what appeared to be objective moral claims were simply the equivalent of cheering or booing ideas or actions of which we happened to approve or disapprove, the latter that they were simply a means by which the powerful manipulated the weak.

Given the importance of the language of love in the Bible, and the ethical significance attached to it, the current moral malaise which surrounds the concepts of ‘love’ and ‘hate’ in our wider culture should be a matter of grave concern to Christians. Recent debates about the relationship of the gospel to social justice are only the most obvious place where the command to love God and to love neighbor take on an urgency. That urgency demands that the terms are given content, that they are not allowed to exist as mere expressions of aesthetic preference or the political and social tastes of the Tweetocrats, be they of the left or the right. Our language—the language which stands at the center of biblical ethics—has been semantically disemboweled even as it has been made almost the only acceptable criterion for public morals, leaving Christian discourse in a perilous condition.

This latter point should be clear from the sweeping statement made in Matthew 22:37-40:

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

The claim in that last sentence is astounding and immediately brings into focus what is at stake in debates over the nature of love—nothing less than the whole ethical dynamic of the Bible. More than that, it also involves the very being and identity of God Himself. A defective understanding of love stands in positive relation to a defective understanding of God.

The reason for this is that the biblical ethics are ultimately anchored in the being of God, such that the content of our ethical language finds its original meaning in God himself. This is clear from Dt. 10: 17-18:

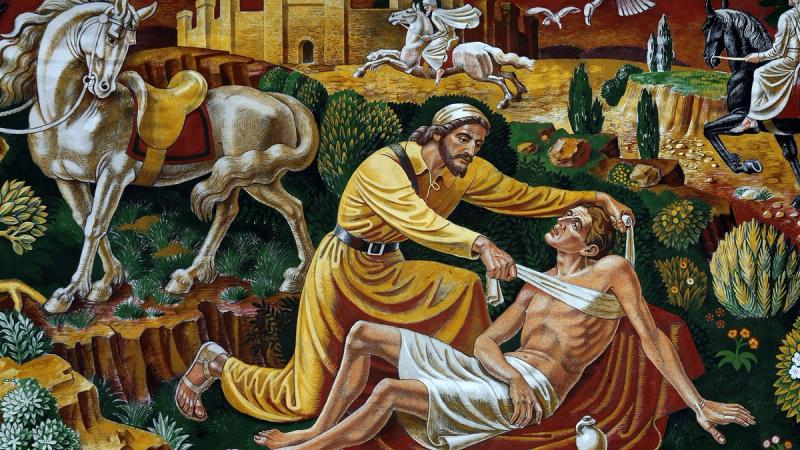

[T]he LORD your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great, the mighty, and the awesome God, who is not partial and takes no bribe. He executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing. Love the sojourner, therefore, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt.

Here, Moses makes it clear that the LORD’s care for the children of Israel in Egypt had a twofold significance: it was a paradigm of what love is meant to look like; and it was an implicit command for the children of Israel to have in an analogous way towards sojourners (and presumably towards orphans and widows) who crossed their path or were part of their community.

All of this is bound up with the purpose of Israel. She is to be light to the nations; her behavior is to be a testimony to who God is, a revelation to other nations of what it should mean in practice to be made in the image of God. Could Israel succeed in this? Not in any ultimate, definitive sense, as she was herself made up of sinful, flawed individuals. But it was still her God–given task, and one that would eventually be perfectly fulfilled in Jesus Christ, whose life of perfect obedience can only be understood as a response to that imperative for God’s image bearers to live in accordance with that image and thus to love God with all their heart and soul and mind and their neighbor as themselves. It is the cross, the ultimate act of self-giving that reveals and enacts this divine love, a paradigm that therefore requires Christ’s followers to give of themselves for God and for others in response to the command to love.

If this represents what we might call a biblical-historical view of at love is to be—something patterned after God’s historic dealings with his people, then we might also offer a more strictly theological approach which is rooted in the inner life of God. The result of all the debates over the identity of God in the fourth century was the Nicene doctrine of the Trinity. This represented the church’s conviction that God was utterly simple—without parts as the later Westminster Confession will express it—yet existed eternally in three subsistences, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in a perfect communion of love.

As a result, the inner, eternal relations of the Godhead mean that the statement ‘God is love’ is not for the Christian a projection of human sentiment onto God nor merely some piece of wishful thinking. It is a statement which has an objective reference and an objective content. It demands a specific divine ontology and it is the archetype for human relationships. When the church is described in the New Testament as being distinctively marked by love, this means that the life of the church is to reflect in some deep sense the inner life of God. When human beings therefore speak of love, the word only really has any stable meaning when it is understood in positive analogy both to the eternal being of God and to his dealings with his people in history. That is why Christians need to guard against sentimentalizing their notions of love, perhaps one of the greatest cultural temptations of our time.

Of course, the easy targets on that front are the advocates of Christianity as (to use the well-known phrase) moralistic therapeutic deism: the Joel Osteens, the health, wealth and happiness hucksters who peddle a gospel without a cross to people who want the benefits of resurrection without the inconvenience of suffering and death. Then there are those who capitulate on every key moral issue on the grounds of love and affirmation. In doing so, they misunderstand the Bible’s teaching on God’s love, and in effect, slander him through behavior that is meant to reflect his being and character, but is actually a contradiction of the same. But there is no ground for complacency among the orthodox—the slander of God is not a monopoly of liberal Christianity. The hierarchy of sins with which the orthodox typically operate is itself too often a function of taste—there are those who explode at the thought that a Christian might occasionally smoke a pipe or enjoy a glass of Scotch but think nothing of lying and slandering others if it suits their cause. There are institutions which use the language of the kingdom to assert their own importance while yet treating individual Christians like so many pieces of garbage. And there are those who spend far more time courageously dripping venom on brothers and sisters in Christ than allowing the world to see their allegiance by the love they have for each other. (Though perhaps such people do reveal their allegiances as they restrict their “love” to those who look and sound like them, defining neighbor as those they happen to like.) Strange to tell, they too have a sentimental view of love: it means that which allows them to be whoever they think they should be and to marginalize, disenfranchise, and dismiss any of those who might disagree with them. All such critics must, after all, be motivated simply by hate.

The biblical teaching on love stands in judgement on both those ‘Hate has no home here’ signs, and the behavior of those in the church who restrict its meaning and its application to those who conform to their political, cultural, ecclesiastical and personal tastes. If Luther had to remind his people that justification by grace through faith did not negate the command to love and nor did it evacuate love of meaningful content, we must do the same. Hate has no home in Christianity because love is not a sentiment.

Carl R. Trueman is a professor at the Alva J. Calderwood School of Arts and Letters, Grove City College.

This article was originally published by Modern Reformation on Oct. 22, 2018.