Two particular events have shaped my approach to writing: the first was a lecture I attended as a schoolboy in the early 1980s, given by Terry Jones of Monty Python fame. The topic was not dead parrots or the unexpected nature of the Spanish Inquisition but Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale” on which he had just published a scholarly book. The second was discovering the essays of Camille Paglia, especially those collected in the volume Sex, Art, and American Culture. My encounters with Jones and Paglia taught me vital lessons: the distinction between high and low culture, while not arbitrary, is porous and more complicated than many acknowledge (and taking the former seriously should therefore not exclude doing the same with the latter), humor could be profoundly didactic, self-parody was vital to the avoidance of self-importance (something lethal to truly good writing), and being a specialist in one discipline need not preclude one from being knowledgeable and able to comment intelligently in other areas. In fact, informed, intelligent generalists are much to be desired.

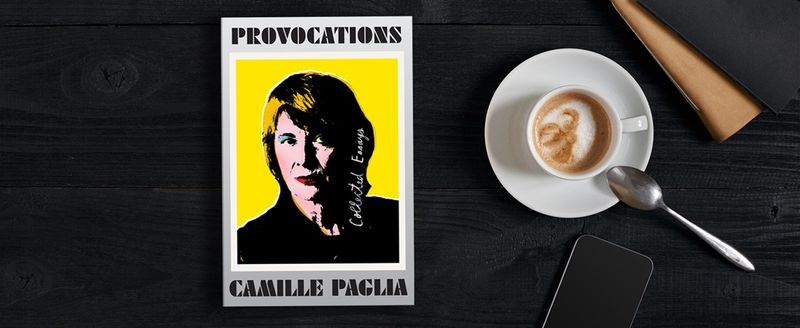

All of those elements are on splendid display in the latest volume of Camille Paglia’s work, Provocations, which contains her major writings from the last twenty-five years of her career, from extended essays to short web interviews. The pieces are thematically arranged, with major sections entitled ‘Popular Culture,’ ‘Film,’ ‘Sex, Gender, Women,’ ‘Literature,’ ‘Art,’ ‘Education,’ ‘Politics,’ and ‘Religion.’

For Paglia aficionados, the volume is simply a delight—there is commentary on the fashions paraded at the Oscars, a sterling defense of Alfred Hitchcock’s artistry, a homage to Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire (surely the greatest American play ever written), and significant essays on the problem of bringing Homer to the screen, the joys of teaching Shakespeare to actors, and the cultural significance of David Bowie. The ease with which Professor Paglia glides between elite and pop culture is as remarkable as ever, and while she will never persuade me that Prince is of great cultural significance, her ability to take seriously artists of all descriptions without patronizing either her subjects or her readers is a rare gift.

For Christian readers, three sections are of particular interest: those devoted to sex/gender/women, education, and religion. To understand why, it is useful to know that key to her thinking is the trenchant rejection of post-structuralism, a form of critical thinking developed most notably by Michel Foucault which, as anyone who has studied humanities in the last thirty years, has been imported into the Anglophone world with a disastrous impact upon education and thence to the kind of political correctness which is spreading like a malignant bacillus throughout our public discourse. Essentially, post-structuralism channeled a tendentious reading of one aspect of Nietzsche’s philosophy (the will to power) mediated via Heidegger and from thence developed an approach to understanding the world that is as simplistic in its basic outlook as it is opaque in its Gnostic prose. In short, everything is reduced to power: who has it and who does not. Once assumed, this allows the legacies of the past—literary canons, philosophies of life, hallowed institutions—to be unmasked as exploitative and hence dismissed.

Professor Paglia took a merciless hammer to such nonsense in the early nineties, with her idol-shattering essay, ‘Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders: Academe in the Hour of the Wolf.’ The essays in Provocations are the fruit of that early iconoclasm. Thus, in an interview with The Weekly Standard in 2017, she is merciless with the current trendy transgenderism which she argues both repudiates biology and plays into the hands of the pharmaceutical industry. Though she herself identifies as transgender, having donned ‘flamboyant male costumes from early childhood on,’ it is clear that she has little time for the notion that identity is simply a function of psychology, with gender being nothing more than a cultural construct imposed by heteronormative society upon the powerless individual. ‘The cold biological truth is that sex changes are impossible. Every single cell of the human body (except for blood) remains coded with one’s birth gender for life.’ (197-98). Indeed, that ‘most men and women on the planet experience and process sexuality differently, in both mind and body, is blatantly obvious to any sensible person.’ (201). The post-structuralist myth, that ‘nature’ is just a mask for power and manipulation, is just that—a myth—and not even a particularly inspiring or persuasive one.

On education, Professor Paglia offers fine defenses of free speech on campus, of canons and of appropriate multiculturalism. In the post-structuralist universe, free speech is a problem; just another white male construct designed to maintain the power structures of the status quo and therefore needs to be overthrown. Not so, says Professor Paglia. In a carefully argued essay, she traces various sources of the contemporary problems of freedom of speech on campus, starting with the balkanization of departments through the fractious influence of new ‘identities’ on traditional disciplines. Where once there were English Departments, now literary studies have been parceled out into African American Studies, Queer Studies, Native American Studies etc. None of these approaches is necessarily illegitimate; but the problem is that the disciplines no longer talk to each other as the old departmental structure would have made necessary. This is reinforced by the tendency in today’s politicized academic institutions to confuse teaching with social work, along with the Gnostic jargon that now dominates literary studies. The answer, Professor Paglia declares, is a return to broad survey courses in world history and culture, structured by chronology not ideology. I was gratified to read this, for it is the philosophy that drives the general education core at my own institution, Grove City College. Though it left me wondering if the balkanization and jargon of which she writes is a scourge only on secular campuses: my experience of the seminary world was that it too has become increasingly jargon-oriented, dismissive of history, internally balkanized and externally isolationist. The cultural context and mindset of political correctness is no monopoly of post-structuralists.

On religion, Professor Paglia is at her most remarkable. An avowed atheist, she understands that human beings are more complicated than the pieties of post-structuralism would suggest. She knows that we have a desire to find meaning; she understands the irrational and often ambiguous power of erotic love; she knows that the human heart has dark corner and sinister recesses. Most importantly, she sees that religion speaks to all of these things in a way that Foucault and his disciples do not. Life is not simply about power; it is also about beauty and ugliness, love and hate, fall and redemption. For her, redemption comes through art; but she acknowledges that Christianity is addressing the same fundamental issues.

This lies behind her comment from 1995: until gay activism ‘gets over its adolescent scorn for religion, gays will continue to lose ground in the culture wars.’ (499) History has proved her wrong on that point—at least thus far. Childish contempt for religion has proved a fundamental part of a remarkably successful decade or two of gay activism. But I wonder if her mistake was not to underestimate gay activism so much as to overestimate the Christian religion. Might it be that many Christians and many churches also have an adolescent attitude to religion? If the church is basically there to meet their needs and give them a platform for public performance, not to provide a place where they can (as Philip Rieff once memorably put it) have the pain and misery of life explained to them, then gay activism has little to fear.

Last year I found myself in serious trouble for publicly declaring my undying love for Professor Paglia online. I had made the mistake of assuming that all readers would have learned from the Warrior Queen what she had taught me so many years ago: the importance of a sense of humor and the ability to understand irony. Alas, I discovered that Professor Paglia is to the Christian world of today what Debbie Harry was to those of us who came of age in the eighties: the woman I really wanted to date but of whom I was certain my mother would never approve. That is sad: Christians can learn much from her work about some of the most fundamental aspects of human existence as well as the deep flaws in dominant schools of secular thought. And, of course, they can also learn how to think and to write with brio, insight and humor. And as I read this volume, I have to confess that I fell in love once more.

Carl R. Trueman is a professor at the Alva J. Calderwood School of Arts and Letters, Grove City College.