I’m coming, I admit, a little late to the party (about 13 years to be exact). Over the past few months I’ve had the opportunity to read Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age.[1] If you haven’t read it yet, the book basically tries to tell the “story” (his word, not mine) of how we got to where we are as a society today—one where belief in God is just one option among many. While I would quibble with Taylor’s historical narrative, I did find Taylor’s description of our day both informative and revealing.[2] For that reason, I want to explore a few of Taylor’s categories (Taylorisms) that I think help the church get a better grasp of the world in which it now finds itself and to which it proclaims the Gospel.

Exclusive Humanism, Cross-Pressure, and the Nova Effect

I begin with three foundational Taylorisms to start, which then build up to a fourth. The three are exclusive humanism, cross-pressure, and the nova effect. What is exclusive humanism? Taylor uses this term to refer to what he sees as the new “religious” option of our day.[3] It pitches itself as a type of third way, a Goldilocks zone between belief and unbelief that borrows aspects of both. What it essentially comes down to is the belief that we can have a world of deep meaning and purpose (belief) without reference to anything higher, like God (unbelief). Exclusive humanism tries to “make a heav’n of [earth],” focusing on this world and happiness in the here and now.[4]

The key word here, however, is “tries.” As Taylor explains, this new exclusive option is, what he calls, inherently cross-pressured—the second term we want to consider.[5] Exclusive humanism exists, so to say, in between belief and unbelief, pulling aspects from both sides. But what also happens is that belief and unbelief pull back. Meaning and materialism don’t go together. And so, there is a strain in the middle where exclusive humanism tries to live. There’s a constant tension within exclusive humanism as it tries to negotiate between the different aspects of belief and unbelief it holds. Cross-pressure describes this strain.

And these different cross-pressures lead to what the book calls the nova effect, our third term.[6] The nova effect describes the way uncomfortable tensions turn exclusive humanism into many exclusive humanisms. The idea is that different cross-pressures tend to push people to work out exclusive humanism in different ways. They try to rework the model, pulling on new strings of belief and unbelief until they find something that works, i.e., gives them a sense meaning and purpose in this world. Within the nova, then, the goal of exclusive humanism largely remains the same while the imagined ways to get there change, like one city with many roads leading to its gate.

A Secular Age

With exclusive humanism, cross-pressure, and the nova effect in place, I add what might be the most important Taylorism in the book: a secular age. One of the central things Taylor tries to do through his pages is give a historical account of how we ended up in a what he calls this secular age. His story spans some 400 pages, charting historical movements from the Middle Ages up to the present. G.K. Chesterton summarizes Taylor’s analysis well:

The modern world is not evil; in some ways the modern world is far too good. It is full of wild and wasted virtues. When a religious scheme is shattered (as Christianity was shattered at the Reformation), it is not merely the vices that are let loose. The vices are, indeed, let loose, and they wander and do damage. But the virtues are let loose also; and the virtues wander more wildly, and the virtues do more terrible damage. The modern world is full of the old Christian virtues gone mad. The virtues have gone mad because they have been isolated from each other and are wandering alone.[7]

For Taylor, a secular age defines a culture untethered from it’s roots that has come into its own. A secular age is nothing more than a time when belief in God is no longer assumed, but one option among many. A secular age is when exclusive humanism popularizes.[8] According to Taylor, to live in this kind of day and age is basically to feel haunted.[9] The number of different beliefs and lifestyles that surround us today are more and closer than ever before. And together they create their own unique cross-pressure: the question of who’s right? In effect, every option haunts the other, making it extremely hard to just accept a faith (whatever that might be) without at least a glance over the shoulder or pull in the other direction. The degree of this may differ from person to person, but it’s something that seems to touch on everybody here or there. It haunts us.

Our Age and the Church

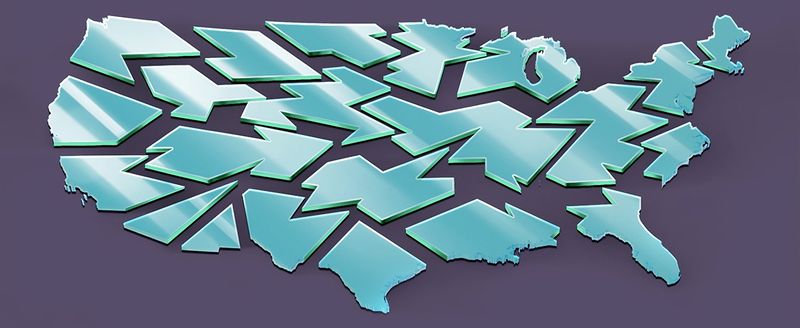

Taylor pictures our age more or less as one of many cross-pressures. As we have tried to close off our world from God and make meaning and purpose on our own, we have created a new tension, a feeling of fragmentation. Yet rather than acknowledge God or abandon meaning, we have continued to try to piece back the picture ourselves. And now, a nova of different “religious” options stands before us with its own daunting pressure: the question of who is right? This question presses upon belief, unbelief, and exclusive humanism, making for a world that in many ways feels haunted. And so, our age wanders, afraid to settle down. In fact, the journey becomes what’s important. Spirituality itself becomes the quest. But even more than that, it becomes my quest, my truth, and my life, your quest, your true, and your life. Authenticity speaks with moral force. Alone together we continue on, driven by the cross-pressures of the nova and our spiritual desires that in some way create it. This is (maybe a bit too glum picture of) the age we live in.

It’s in light of this analysis, that I offer some reflections on three ways Christians and the church can use Taylor to bring the Gospel to our secular age.

First, we can speak to this age by acknowledging the attraction of the different religious options today. Beyond understanding what people believe, we should also try to understand why they believe it. And I am not just talking about the facts, but the story behind them—why is the other option attractive? Why would someone want to believe it? What’s the narrative? Consider how C.S. Lewis does this with evolutionism (the world view, not the scientific theory):

It is one of the most moving and satisfying dramas which has even been imagined. The drama proper is preceded (do not forget the Rheingold here) by the most austere of all preludes; the infinite void and matter endlessly, aimlessly moving to bring forth it knows not what. Then by some millionth, millionth chance—what tragic irony!—the conditions at one point of space and time bubble up into that tiny fermentation which we call organic life. At first everything seems to be against the infant here of our drama….But these were only growing pains. In the next act he has become true man. He learns to master nature. Science arises and dissipates the superstitions of his infancy. More and more he becomes the controller of his own fate…we follow our hero on into the future. See him in the last act, though not the last scene, of this great mystery. A race of demi-gods now rule the planet.[10]

Lewis beautifully gets behind evolutionism here to capture the story it offers. He shows how the force is not so much in the facts, but the story it tells.[11] Being able to understand in this way why people believe opens up all sort of points of contact for the Gospel.

Second, we can speak to this age by recognizing that much of the conversation is over different visions of the good life. People today who buy into exclusive humanism and an ethic of authenticity do not think they are doing something wrong when they do. Morally, they think they are right. They see it as a good. And so, often the greatest tact is to explore how “good” their vision of the good life really is—What are you living for? How do you define success? How do you deal with loss? David Foster Wallace does something like this in his speech “This is Water.” He says:

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you.

Wallace doesn’t directly attack belief or unbelief here, but simply shows where different beliefs will end. Not all visions of the good life end at the good. And that’s what we should try and draw out too. We should press on the inadequacy of different visions of the good life and how Christianity offers a better way.

Finally, we can speak to this age by preaching the whole council of God. If Scripture really is the Word of God, then we are sinners in need of the forgiveness that is only found in Jesus Christ. When we make the Christian message ultimately something different than that, we not only distort Scripture, but we lose our ability to explain and haunt the world. When Christianity stops being Christian, it loses its pull. And so, we should not try to change doctrine in some way to reach our age. Rather, we need to be able to explain to a largely unchurched and Biblically illiterate people how Scripture and its doctrines articulate their deepest intuitions. For example, how might our cancel culture point beyond itself to desire for God’s judgment on sin and evil? How might political allegiances betray a greater understanding of federal headship? How might unmet desire point beyond this world? As G.K. Chesterton once said, “This, therefore, is, in conclusion, my reason for accepting [Christianity] and not merely the scattered and secular truths out of [Christianity]. I do it because the thing has not merely told this truth or that truth, but has revealed itself as a truth-telling thing.”[12] We can only truly help this world if we bring the truth to it. And that means the Gospel and all it entails for it was Jesus who said, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

Caleb Frens is a graduate from Westminster Seminary California. His interests include philosophy, theology, and all things The Office.

[1] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age(Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2007).

[2] For two brief historical critiques of A Secular Age, see Carl Trueman, “Taylor’s Complex, Incomplete Historical Narrative,” and Michael Horton, “The Enduring Power of the Christian Story: Reformation Theology for a Secular Age,” in Our Secular Age: Ten Years of Reading and Applying Charles Taylor, ed. Collin Hansen.

[3] For a historical account of exclusive humanism, see Taylor, A Secular Age, 221-269. Taylor does not specifically define exclusive humanism in his book. Any definition must piece together several aspects of his historical account. This is true of many of the Taylorisms defined in this essay.

[4] John Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. John Leonard (New York: Penguin Classics, 2003), 1.221-270.

[5] See, e.g., pp. 303, 378, 548-549, 600.

[6] Ibid., 302, 303, 310.

[7] G.K. Chesterton, Heretics and Orthodoxy: Two Volumes in One, 193.

[8] A Secular Age, 19-20.

[9] I get the term “haunted” from James K.A. Smith, How (Not) to be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014). Taylor never actually uses the word himself, preferring “fragilization” and “fragmentation” instead. See A Secular Age, 20-21, 302, 308, 378, 437, 531.

[10] C.S. Lewis, “The Funeral of a Great Myth,” in The Seeing Eye: And Other Selected Essays From Christian Reflection, 119-121.

[11] This is a point Taylor makes throughout A Secular Age, 361-374.

[12] Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 311.