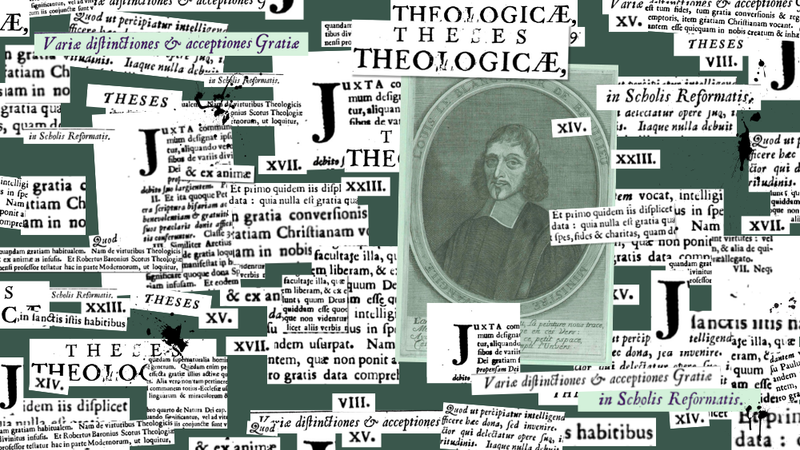

By Louis le Blanc

Translated by Michael Lynch

The following is a translation of pages 516–19 from Louis le Blanc’s Theses Theologicae; Variis Temporibus in Academia Sedanensi Editae, et ad Disputandum Propositae (Theological Theses Given at Various Times at the Academy of Sedan and Proposed for Disputation) first published in 1683 in London by Moses Pitt.

- The common opinion of the doctors of the Reformed school is that grace very often designates the love and favor of God by which he pursues us who are undeserving of it, but also sometimes designates his gifts and the effects created by those gifts. Accordingly, [Daniel] Tilenus, in his theses on the various names of the divine will, teaches that God’s grace is understood actively and passively. “The former,” he says, “signifies the beneficent and favorably-disposed will of God granting all things freely and graciously, neither on account of our merit, nor as something due to us. The latter denotes some gift graciously given.”

- And so, also, Peter Martyr [Vermigli] in his Common Places says, “The word grace in Sacred Scripture has a twofold meaning. First and principally, it signifies the gracious favor and benevolence of God towards men by which he pursues the elect. Then, because God bestows upon his elect these gifts, it sometimes also signifies those gifts which are graciously conferred upon us by God.”

- Similarly, [Benedictus] Aretius in his Common Places teaches that when the Sacred Scriptures talk about grace, this word, in the first place, means the gracious mercy of God by which God manifests himself in the reconciliation and justification of man. Then, [secondly], the word grace also signifies the gifts of the Holy Spirit. In the same work, Aretius acknowledges that these gifts can rightly be called infused grace. [Amandus] Polanus’s distinction amounts to the same thing. “The grace of God,” he says, “is equivocal [ὁμωνύμως], for it is either residing in God or given by God.”

- But even though Reformed theologians acknowledge that the gifts and effects of divine favor and love towards us are sometimes designated in sacred Scripture as God’s grace, nevertheless, they think there are only a few places that grace is used in that sense. Indeed, they argue that all those places where we are said to be chosen, called, justified, and saved by God’s grace, ought not to be interpreted as denoting some gifts inherent in us, but only the gracious love and benevolence of God. This can be seen especially in Polanus. He says, “The grace making a person favorable or acceptable to God, and hence, the saving grace by which we have been chosen in Christ to eternal life, effectually called, justified, regenerated, and by which finally we are eternally saved, is not an infused quality within us, nor is it something inherent and created in us, nor the love by which we love God, nor any other virtue in us.”

- Moreover, when grace is interpreted as the gifts and effects of divine favor, Tilenus observes that in a general sense it includes common nature itself and the gifts and talents of that nature, even though, properly speaking, it is restricted to certain supernatural gifts granted by God to mankind. These gifts, again, he takes to be of two kinds. For some [gifts] properly and directly pertain to the salvation of the one who receives it, such as the effects of that active grace by which God justifies us. These are faith, hope, and love. But some [gifts] pertain more to the common use and edification of the whole church than to the personal salvation of those to whom they are given. Such are the gifts of prophecy, tongues, miracles, and others like these.

- What [Girolamo] Zanchi teaches in his small book On the Nature of God amounts to the same thing. He says that those gifts of God which are sometimes signified by the word grace either pertain to eternal life, such as faith, hope, and love and those virtues conjoined with them, or do not pertain to eternal life, such as the gift of tongues, of miracles, and others as Paul says in 1 Cor. 12. Polanus also says something like this in the aforementioned place.

- [John] Cameron’s distinction does not greatly differ [from above] when he says that none of the gifts of grace belong to any persons who are not also saved. But there are other gifts which even fall upon those who are not saved. Likewise, God’s gifts are to be distinguished between those which profit others only, but not us—of which sort are all the gifts of God granted to the impious; and those which often profit others, sometimes do not profit them, yet always profit those upon whom they are bestowed—of which sort are faith, hope, and love.

- But those divisions of the gifts of grace used by the Reformed hardly, or do not at all, differ from the customary schoolmen division of grace into gratuitously given grace and grace which makes a person acceptable, as Tilenus acknowledges in the previously cited disputation. However, most Reformed theologians vilify and criticize that distinction of the Roman school. Indeed, the first thing that displeases [the Reformed] is that some gifts of God are particularly said to be gratuitously given grace. Yet [for the Reformed], there is no grace which is not gratuitously given. Faith, hope, and love are no less gratuitous gifts of God than are the gifts of prophecy, healing, and similar ones.

- Moreover, they do not accept the idea that something created and inherent in us called grace is making us pleasing and acceptable with God, as can be seen in Polanus, Aretius, and Peter Martyr in the aforementioned places. They do not deny that the gifts of God, which the doctors of the Roman school designate as grace which makes a person acceptable, are something pleasing to God, by which God is delighted, and which itself is acceptable. Yet, they deny that God’s favor with mankind is first obtained by those gifts since those gifts themselves are the effects of divine favor and love and proceed from God favoring us and loving us, even before we accept them, just as John said: “Not that we loved God, but because he first loved us.”

- Indeed, it is clear that this is the position of those doctors from their very words. For Peter Martyr speaking about the infused grace of the Scholastics says: “It is no small error that they want us to be made acceptable to God by this habit or creature. For it was necessary, given that he had bestowed upon us a gift of this kind, that he love us first. For the love of God precedes all of his gifts.” And he says, “They err no less who drone on about some grace being gratuitously given and other grace being that which makes a person acceptable. For every grace necessarily is gratuitously given. Otherwise, as Paul says, it would not be grace. And given that they understand the grace which makes a person acceptable to be habitual (as we taught above), they wrongly think that human beings are made acceptable to God by such gifts. For with him we are received into his grace by his mercy alone and on account of Christ.”

- And similarly, Cameron, in the aforementioned digression about grace, “However, it should be observed that God’s gifts are never called grace in this sense, as if God’s favor could be procured by them and as if those gifts could make us pleasing and acceptable to God. But if at any time God’s gifts are called grace in this sense, one has in mind the perspective of human beings, who by these gifts are led into love, but not God’s perspective. In order to perceive this, we should understand that the human love which is caused by these gifts does not effect these gifts, but finds them. And the same divine love finds and effects these gifts, just as a painter who delights in his own painting is the same one who rejoices because of the beauty of the painting and was the author of that beauty. Therefore, properly speaking, no grace ought to be called grace which makes a person acceptable, but rather it ought to be called grace of the one making a person acceptable.”

- From this, it is clear that the Reformed doctors do not deny that faith, hope, love, and similar gifts of the Holy Spirit are acceptable things to God and, on account of these things, a person in whom they are found is pleasing and acceptable to God. But the Reformed doctors only deny that those gifts do not come previous to God’s favor and love towards us, but are its effects and gifts.

- Additionally, Tilenus does not seem to criticize anything else in the Scholastics on this point than that they confound those gifts of grace which the Scholastics call grace which makes a person acceptable with justifying and saving grace, which according to the position of Reformed theologians, is not something inherent in us, but only the active and external grace of God. For speaking about hope, faith, and love, he says: “The Scholastics call this grace grace which makes a person acceptable, and they most-dangerously confound it with that active grace.”

- Also, some of the doctors of the Reformed school even admit the distinction of grace into grace gratuitously givenand grace which makes a person acceptable, but in a different sense than how it is received among the scholastic doctors. For [Paul] Testard in his Irenicum understands grace gratuitously given as that grace by which God invites a person to salvation. But he understands grace which makes a person acceptable as that grace by which God effectually changes, converts, and sanctifies a person. Or, grace gratuitously given is a certain genus, but grace which makes a person acceptable is a species of that genus by which faith is produced in a person, sins are remitted, and holiness is infused. He says, “We can grant the distinction between grace gratuitously given and grace which makes a person acceptable so that the grace gratuitously given is said to be that which only precedes by way of invitation on God’s part, which is [grace] of a general kind; grace which makes a person acceptable, which is also graciously given, but by effectually changing a person, makes the person acceptable and pleasing rather than detestable. Or, grace graciously given is the most general genus of grace and denotes every grace, but grace which makes a person acceptable is that species of grace graciously given, which produces faith, remits sins, sanctifies, in a word, prepares the subject.”

- Moreover, [Andre] Rivet in his Sum of Controversies understands grace graciously given as all the gifts of grace; but he wants the grace which makes a person acceptable, which he also calls grace graciously being given, to be understood as the very favor of God, by which those gifts arise. It is in this sense that Paul Ferry in his Specimen of Scholastic Orthodoxy uses the same distinction. For, by grace which makes a person acceptable he means a grace immanent to God, which does not place something with the one graced, but is itself the love of God. But for grace graciously being given he understands all the benefits of calling, justification, etc. given graciously from grace, like an abundant fountain descending upon us.

- However, one cannot find many of the Reformed doctors expressly using the distinction of grace into actual and habitual grace. Indeed, some of the older Reformed doctors seem to repudiate the distinction. For example, Peter Martyr in the place cited above directly refutes the position of the Scholastics who hold, as he says, that grace is an infused habit in the soul. But more recent doctors of the Reformed school, as even many of the old ones, acknowledge that a certain habitual grace is given. For they speak about the theological virtues as they do about divinely infused habits. And Robert Baron, the Scottish Professor of Theology at the Academy in Aberdeen, says, speaking on this point about the modern theologians, that it is the unanimous consensus of theologians. And even William Ames extensively defends this view about habitual grace against [Nicolaas] Grevinchovius in his reply to Grevinchovious’s response.

- But I do not think that those of the older theologians who seem to differ actually disagree. For when they dispute with the Scholastics, saying that grace is not a habit infused in the soul, they are clearly dealing with justifying grace. Therefore, their position is not simply that no habits of virtues are infused into the souls of the faithful by God through the Holy Spirit, and that those kinds of habits are nowhere designated by the term “grace,” but instead [they want to insist] that the grace by which Scripture says we are saved and justified in no way depends upon those holy habits. Instead, that grace particularly signifies the mercy and benevolence of God. The reason for this is that they not only deny that the grace (at whatever time) by which we are saved, justified, indeed by which we are also regenerated, is a habit and infused quality, but also that it is anything created and inherent in us, as we noted from Polanus above. And yet that same Polanus, in that same chapter, acknowledges that there is a certain inherent grace which, he says, is both faith and the grace of conversion and regeneration, which grace of Christ our Redeemer the older writers likewise call Christian grace. And therefore, when he denies regenerating grace to be anything created and inherent in us, he only has in mind the efficient and impulsive cause of our regeneration, not the cause which the Scholastics call “formal.”

- But whether there is given a certain habitual grace immediately penetrating and affecting the very essence of the soul besides the habits of virtues, as many of the Scholastics think, most doctors of the Reformed school do not expressly deal with this question; but it does not seem to be much different than that there is a new and supernatural being as well as a renewal of all the habitual faculties, which they acknowledge is granted in a person’s regeneration. Nevertheless, Paul Ferry, the pastor of the church in Metz who recently died, openly acknowledged a certain grace of this kind. And he thinks that before the very act of conversion, a certain habitual grace is infused into the very substance of the soul which penetrates the whole soul like some spiritual light, and from the substance of the soul works its way into all of its faculties. And so, it prepares these faculties to follow the lead of effectual grace, and they easily and spontaneously obey it. This can be seen in that homily which he publicly presented on Hebrews 12:28. But I know that many do not accept this view.

- The distinction of grace into arousing and helping grace is not used as frequently in the Reformed school as it is in the Roman school. Nevertheless, that most-learned Ferry mentions it and seems to approve of it in that homily just cited. And the British theologians at the Synod of Dordt also use that distinction.

- Yet, the doctors of the Reformed school do not disapprove of the fact that the Scholastics distinguish grace into operating and cooperating grace. But with the more recent Thomists, they prefer to understand operating grace as that by which someone is first converted to God. But they understand cooperating grace as that by which someone who has already been converted to God is moved to do good. Accordingly, Aretius in the place cited above says: “Grace is sometimes operating, sometimes cooperating. The former is said to heal and change our will for the better. The latter strengthens that change and causes us to live well.”

- So also, Peter Martyr in that frequently mentioned place says that operating grace is what initially heals and transforms our will. But cooperating grace is what causes that transformed and healed will to do well. To this he adds that operating and cooperating grace is one grace, not two. The reason for the distinction, then, is that the will, when it is first healed, concurs with grace passively: “for,” he says, “the will is said to be changed, and we are said to be regenerated. But afterwards, it acts both actively and passively. For being driven to action by God, it also wills and elects.”

- Nevertheless, neither he nor other Reformed deny, therefore, that the first act of conversion is a vital act and an action by that ability, which the will is said to elicit in us. Indeed, they do not deny that it is a free action and what is called by a number of them a “human” action in the schools. They only insist on this: that when God converts a person, that which grace first works in us is something which entirely precedes the free motion of a person to the good. And thus, on this point, the Reformed do not seem to differ from the saner among the Scholastics, although they express their view with different words.

- The doctors of the Reformed school also acknowledge the distinction of grace into prevenient and subsequentgrace, but they all do not mean the same thing. Aretius wants prevenient grace to be the same as operating grace and subsequent grace to be the same as cooperating grace, which is what many of the Scholastics also think. “For,” he says, “prevenient grace is that which precedes the will so that the beginning of conversion is not by us, but by God’s mercy. Subsequent grace denotes those new motions and good works which follow our conversion, all of which we cannot effect without grace.”

- But Martyr wishes that grace sometimes be called prevenient and at other times subsequent, because God’s mercy furnishes us with many different gifts in a particular order. So that every prior grace can be said to precede one that follows. He says: “For first our will is healed, and it being healed, it begins to will well. Afterward, those things that it wills well, it begins to execute; then, it perseveres in doing well. And finally, it is crowned. Therefore, grace precedes our will in healing it; the same grace follows in effecting that those things which are right will be pleasing. It precedes so that we would will; it follows by driving us to perform those things which we will. It precedes by moving us to good works; it follows, by giving perseverance. It precedes by granting perseverance; it follows by crowning it.”

Footnotes

For more on le Blanc, see “Louis le Blanc: Ghost of Tiresias” by Michael Lynch, Modern Reformation Online Exclusive (March 18, 2022), https://modernreformation.org/resource-library/web-exclusive-articles/louis-le-blanc-ghost-of-tiresias/.

BackDaniel Tilenus, Syntagma Disputationum Theologicarum in Academia Sedanensi Habitarum (Herborn: Christophorus Corvinus, 1607), XIV.20, 113.

BackPeter Martyr Vermigli, Loci Communes (London: John Kingston, 1576), III.2.7, 528. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places (London: Henry Denham and Henry Middleton, 1583), 48.

BackBenedictus Aretius, S. S. Theologiae Problemata Hoc Est: Loci Communes Christianae Religionis, Methodice Explicati (Bern: Joannes le Preux, 1604), loc. 25, 80.

BackAmandus Polanus, Syntagma Theologiae Christianae (Hanau: Wechel with Johannes Aubrius, 1615), II.21, 163.

BackPolanus, Syntagma Theologiae Christianae, II.21, 163.

BackGirolamo Zanchi, De Natura Dei, Seu de Divinis Attributis (Neustadt an der Weinstrasse: Willhelm Harnisius’ Widow, 1598), IV.2.1, 446–48.

BackPolanus, Syntagma Theologiae Christianae, II.21.

BackJohn Cameron, Praelectionum in Selectiora Quaedam Novi Testam. Loca, Salmurii Habitarum, Primus Tomus (Saumur: Cl. Girard & Dan. Lerpinière, 1632), 154.

BackTilenus, Syntagma Disputationum Theologicarum, XIV.22, 114.

BackVermigli, Loci Communes, III.2.8, 529. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places, 49.

BackVermigli, Loci Communes, III.2.14, 532. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places, 50 [Le Blanc wrongly cites III.2.13].

BackTilenus, Syntagma Disputationum Theologicarum, XIV.22, 114.

BackPaul Testard, Ειρηνικον seu Synopsis Doctrinae de Natura et Gratia . . . (Blois: Martinus Huyssens, 1633), CCC, 260–61.

BackAndre Rivet, Catholicus Orthodoxus, sive Summa Controversiarum Omnium inter Orthodoxos & Pontificios … in vol. 3 of Opera Theologica (Rotterdam: Arnoldus Leers, 1660), IV.2 [p. 379].

BackPaul Ferry, Scholastici Orthodoxi Specimen … (Geneva: Joannes Lambertus, 1616). [This work could not be located for a full citation].

BackVermigli, Loci Communes, III.2.8 [p. 529]. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places, 48–49.

BackRobert Baron, Philosophia Theologiae Ancillans … (Amsterdam: Joannes Janssonius, 1649), 180.

BackWilliam Ames, Guil. Amesii ad Responsum Nic. Grevinchovii Rescriptio Contracta. Accedunt ejusdem Assertiones Theologicae de Lumine Naturae & Gratiae (Leiden: Guiljelmus Brewsterus, 1617), cap. 10, esp. pp. 146ff.

BackPolanus, Syntagma Theologiae Christianae, II.21 [p. 170].

BackPaul Ferry, Sermon de la Grace (Amsterdam: Jean Revestein, 1655).

BackFerry, Sermon de la Grace.

BackCf. Acta Synodi Nationalis, … Dordrechti Habitae Anno MDCXVIII et MDCXIX. Accedunt Plenissima, de Quinque Articulis, Theologorum Judicia (Leiden: Isaac Elzevirus, 1620), Pars Secunda, 129–30.

BackAretius, S. S. Theologiae Problemata, loc. 25 [p. 80].

BackVermigli, Loci Communes, III.2.13 [531]. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places, 49.

BackVermigli, Loci Communes, III.2.13 [531]. In translation: Vermigli, The Common Places, 49.

Back