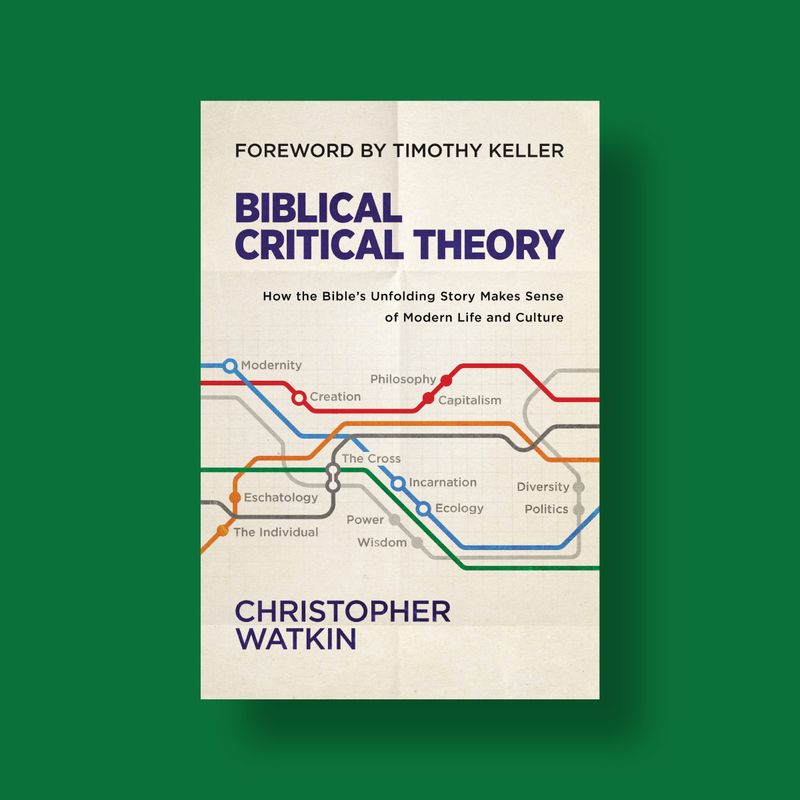

Zondervan Academic | 2022 | 672 pages (hardcover) | $39.99

Over the past few months, I have recommended Biblical Critical Theory to more than a few fellow believers. Almost every time, I was met with a dubious look. The phrase “critical theory” carries negative connotations for many Christians. More than once, a diatribe began against critical race theory before I could explain that this book is something very different.

As Tim Keller notes in the foreword, “The term critical theory has an older and more basic meaning” than those we often hear in contemporary debates: “It means to not just accept what a culture says about itself but also to see what is really going on beneath the surface” (xv). This gets to the matter of “worldview” or how we see and interpret the world around us. As Christians, our worldview is fundamentally shaped by Scripture, though we don’t often consider how exactly the Bible can and should affect our view of reality.

In Biblical Critical Theory, Christopher Watkin helps us further adjust our worldview in the light of Scripture. Watkin does this in unique fashion by walking us through the storyline of Scripture, unpacking the implications for our thinking along the way. Good luck trying to shelve this book in a library! It doesn’t fit with systematic theology, biblical hermeneutics, or Christian living. It encompasses all three.

In addition to the creative organization of this book, the sheer enormity of its scope is impressive. This shouldn’t be surprising. We’re talking about how the Bible shapes our view of the world. What could possibly lie outside such a scope? As a result, Watkin engages many of the hardest philosophical dilemmas and dichotomies—like unity and diversity, rationalism and irrationalism—in the light of Scripture. Yet, he constantly vacates the ivory tower to address ground-level issues.

While Watkin’s writing gets a bit heady at times, he adds just enough quotes, pop culture references, and elegant turns of phrase to keep the reader’s attention. I’m not sure I’ve ever read another book that quotes both G. K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy and Michael Jackson’s “Beat It.” Watkin’s impressive oeuvre of literary sources and knowledge of contemporary culture keeps the tone conversational.

One of the most important concepts Watkin introduces is that of “diagonalization.” He shows how the Bible eschews false dichotomies and partial truths and transcends them. For example, various worldviews favor God’s transcendence at the expense of immanence or vice-versa. The Bible shows us that God is both—not in some 50/50 balance, but in a way that allows these truths to hang together in a manner that only God can do.

Already, the Christian blogosphere has lit up with critiques of this concept, calling it—among other things—“third wayism.” In other words, Watkin is being accused of theological compromise. This accusation totally misses the mark. This concept of diagonalization is unique in that it refuses to compromise with oversimplifications of reality. The Bible is neither the handbook of the rationalist nor the irrationalist, for example, but the God-breathed word that can be reduced to either school of thought. (Unfortunately, quality theological work generally does not thrive in the humming hive of online Christian punditry.)

If the book has one partial weakness, it’s this: Due to the sheer scope of the book, a good many important discussions and ideas are abbreviated and underdeveloped. Occasionally, Watkin whets my appetite and then leaves me unsatiated. I’m not sure whether he really had a choice—the book is nearly seven hundred pages as it is. In spreading the feast of thinking biblically for all of life, perhaps Watkin could offer only limited portions lest the reader overindulge.

Yet, this arguably unavoidable weakness creates another subtle strength to this work: It introduces several academic roads less traveled. Embedded within nearly every perfunctory point is the question, “Couldn’t this idea be further developed?” If Helen of Troy had the “face that launched a thousand ships,” then Biblical Critical Theory will be the book that launched a thousand dissertations.

This may very well be my favorite book of the year. In how it will both start and shift conversations within the church, it should be equal in influence to Carl Trueman’s Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. Although this isn’t fodder for Sunday school, it will likely produce a secondary wave of writing that will be immensely important for Christians in the pew. It belongs in every church office and every seminarian’s already over-weighted bookcase. In an age of reactionary heat, we should be thankful to the Lord for books like this that enable a new generation of scholars to view the world with biblical critical lenses—and thus with greater light.