It’s no secret the church in America is struggling. We’ve lost the cultural wars, and our kids are being seduced by the siren call of secularism. It’s rare to find a family where I live in the Northeast where all the grown children of Christian parents are believers. Having lost the cultural high ground, we no longer control the public narrative. Last night one of my favorite British sitcoms, Doc Martin, mocked a missionary couple as judgmental, selfish, and greedy. That’s not just a lie, it’s a false narrative that is imprinting our youth.

It’s no different from the false narrative that the slaveowners spun of Paul and Silas in Philipi after Paul cast the demon out of their slave girl. Trapped by the false narrative of the slaveowners (“these Jews are troublemakers”), Paul and Silas ended up beaten and in prison with their legs in stocks (which functioned like torture extenders). There in prison they embraced a “fellowship of his sufferings” (Phil. 3:10) by instinctively forming a praying community.

With the cultural supports of Christendom gone, we often find ourselves in situations where we are powerless and suffering, like Paul and Silas. Only in our reenacted Gethsemanes does prayer become like breathing. That’s my hope and prayer: that as suffering increases, our churches would learn to be praying communities.

Unfortunately, praying Christians are rare. In our prayer seminar, we ask several confidential questions about a participant’s prayer life. After doing hundreds of seminars, we have found that about 85 percent of Christians in a typical church do not have much of a prayer life. So when someone says, “I’ll keep you in my prayers,” 85 percent of the time it is just words. There is no prayer life to keep these prayers in.

Even rarer is a praying church, where a whole community prays together. That’s the vision of this article: First, to understand the problem of prayerlessness, particularly in church leadership, then to discover the solution that centers on a new vision of the church, and finally to see what a praying church looks like. To do that, I need to go back fifty years.

The Problem of Prayerlessness in Leadership

After my father, Jack Miller, joined the faculty at Westminster Theological Seminary in 1968, he visited Francis Schaeffer in L’Abri, Switzerland, where he encountered something he’d never seen before—a praying community. Prayer operated at the center of L’Abri’s life. That is, the life of the community orbited around the prayer meetings. Here are Edith Schaeffer’s reflections on what a praying community looks like:

Common sense Christian living takes place in an atmosphere where prayer is as natural as breathing, as necessary as oxygen, as real as talking to your favorite person with whom there is no strain, as sensible as reaching into the bag of flour for the proper supplies for making bread. To live without prayer being woven into every part of every day is stupid, foolish, senseless, or is an evidence that your belief in the existence of the Creator, who has said we are to call upon Him, is an unsure belief.1

Dad was an ordained minister in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, a seminary professor, and a newly minted PhD, yet prayer operated at the periphery of his life. He was not alone. Multiple pastors have confided in me how difficult prayer is for them. After attending three prayer seminars, one of the leaders in my denomination (Presbyterian Church in America) confided in me how hard it was for him to be faithful in his prayer life. Recently at lunch, several Southern Baptist church planters said to me, “Planting a church killed my prayer life.”

For most pastors, prayer doesn’t function at the nitty-gritty level of life the way their calendars or phones do. Apart from public prayers during worship services, they pray at the beginning of meetings, but this prayer tends to be official and lack depth. For example, when I meet with pastors, I’ll share my particular sexual temptations, how I pray about them, and how God has helped me. Then I ask, “How do you pray about your sexual temptations?” Dead silence.

Then I’ll probe from another direction. Most pastors struggle at times with successful businesspeople in their church who bring a wealth of practical experience. The pastors, often with little practical business experience themselves, need their wisdom and help, but pastors will recoil from the way these men and women exercise power in the church. So I ask, “How are you praying about strong men and women in your congregation?” Again, dead silence. So, in two of the most challenging areas of their ministry—sex and power—many pastors are functionally on their own.

There are multiple roots to prayerlessness: unbelief (the functional atheism of our public culture gets in our blood), materialism (money does what prayer does but lets you remain in control), and cynicism (what good does prayer do?). But the problem isn’t merely “sin.” Prayerlessness is pervasive in the church, and the problem has deeper roots. Something is missing.

Defining the Problem

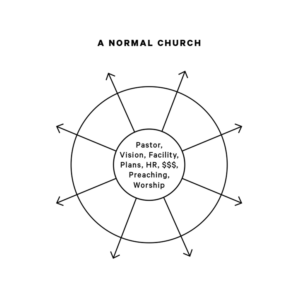

This chart helps define the problem of prayerlessness in the church:

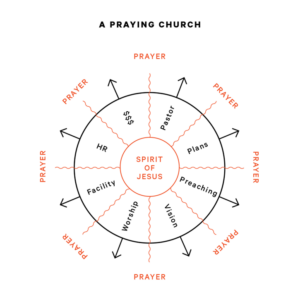

Every element in this chart is important and good. The arrows on the outside show how the church is reaching into the broader world with mission. At the core of the church are important ingredients: the pastor, preaching, plans, worship, and so on. Each item helps make a successful church. The one oddity is how weak prayer is. I’ve represented this by graying out “prayer.” Here is a more biblical blueprint:

The “A Praying Church” chart has all the elements in “A Normal Church,” but the elements don’t operate at the core; the Spirit of Jesus does. Prayer becomes central because the Spirit, who carries Christ to us, is central.

Attentiveness to the Spirit of Jesus is the missing key to the church’s prayerlessness. Pastors struggle with prayerlessness not primarily because of ego or self-will or even self-discipline. It is because of the way they view the church. They have the wrong blueprint.

In the absence of the Spirit, what quietly moves to the center of the church life is the managerial and, to a lesser extent, the therapeutic. The good manager sees the facts, the processes, and the people the church needs. None of this is inherently wrong, but it often misses the central fact in any church: the Spirit’s resurrection of Jesus from the dead and the ensuing life and power that come from their union. That blinding light shapes all other wisdom.

This biblical chart gives rise to three questions, which we will answer in the following order: Why is the Spirit of Jesus so important? Why is prayer so central to the work of the Spirit? And what does this look like in a church?

The Missing Spirit of Jesus

After visiting L’Abri, Dad still didn’t know why prayer was critical for the life of the church—until he took a sabbatical in Spain in the summer of 1970. In the writings of Princeton scholar Geerhardus Vos, Dad discovered that the end time had already begun on Easter morning with the resurrection of Jesus and the pouring out of the Spirit.2 We now live in the age of the Spirit.

Dad was captured by Ezekiel’s vision of the river of grace flowing out of the new temple (Ezek. 47). Everything the river touches comes alive. The further out the river goes, the deeper it gets. Jesus picked up Ezekiel’s visions at the end of the Feast of the Tabernacles, when huge vats of water were poured out in the temple symbolizing the poured-out Spirit in “the last days.” Jesus stood up and cried out,

“If anyone thirsts, let him come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as the Scripture has said, ‘Out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.’” Now this he said about the Spirit. (John 7:37–39)

At the same time as Dad, another Westminster professor, Richard (“Dick”) Gaffin, read Vos and made similar, parallel discoveries. What my dad developed practically, Gaffin developed in his biblical studies. Here’s how most translations translate 1 Corinthians 15:45 (emphases added):

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam [Jesus] became a life-giving spirit.

But Vos and Gaffin point out that Paul really says:

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam [Jesus] became life-giving Spirit.

Notice the difference. Jesus becoming a life-giving spirit merely suggests that the resurrected Jesus gives life, while becoming life-giving Spirit means that in the resurrection Jesus is so united with the Spirit that Paul can say Jesus became Spirit.

On the first Easter morning, the Spirit transformed Jesus’s lifeless body into a Spiritual body (1 Cor. 15:44).3 The Spirit unites with Jesus so intimately that, without losing their separate identities, Jesus and the Spirit become functionally one.4 They are so united that Paul easily interchanges “Spirit” and “Lord” or joins them in a single phrase, “the Spirit of the Lord.” So Paul writes,

Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit. (2 Cor. 3:17–18; emphasis added)

The Spirit now carries Christ to us. Or to put it simply, the incarnate Son of God is dependent on the Spirit not only for his life but to “get around.” Mysteriously, Jesus, as the Son of God, fills the universe, but he can only get into “the rebellion” through the Spirit.5

Paul repeatedly links Christ’s life by the Spirit with our life by the Spirit. If Jesus lives by the power of the Spirit, then so do we. The Spirit made Jesus’ body come alive, and he now makes Jesus’ body on earth—the church—come alive. So what does that have to do with prayer?

Prayer and the Spirit

The apostle Paul makes a tight connection between the Spirit and prayer that looks like this: Prayer ▶ Spirit ▶ Jesus. Here’s one of the many places Paul lays out this pattern:

For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love. (Eph. 3:14–17)

Notice Paul’s pattern: he prays to the Father, for the gift of the Spirit, who in turn brings Christ. A praying community makes space for the Spirit, who in turn brings us Jesus. That is the church’s most basic need.

This explains something unusual about Paul’s gift lists. Some people are clearly better at praying than others, and yet prayer is never mentioned as a gift. Why? Prayer is so fundamental to the life of the church that it is not a gift. It’s like breathing. It is not an option; it’s the engine.

History of a Praying Church

From the very beginning, prayer has been fundamental to the life of the church. The first mention of the people of God defines us as a praying people: “At that time people began to call upon the name of the Lord” (Gen. 4:26).

Solomon dedicated the temple as a “house of prayer,” not by preaching a sermon but by praying about prayer. Solomon describes seven different problems (war, famine, and so on) that might confront the people of God, and each time he asks God, “When they pray towards this house, hear in heaven.” Isaiah expands this invitation to the Gentiles, “For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (56:7).

Solomon’s vision of the temple, as a house of prayer permeates the Gospels. Multiple events happened in the temple (sacrifices, giving, teaching), but Jesus describes the Pharisee and the tax collector as going up to the temple to pray. Jesus clears out the temple with a whip because it had ceased to be “a house of prayer.”

This same praying spirit permeated the early church. Tertullian (AD 200) wrote: “We gather in an assembly . . . and, as if we had formed a military unit, we force our way up to God by prayer. This power is pleasing to God” (Apologeticus). Likewise, Augustine (AD 400) tells us that prayer was so fundamental to the church that Christians said “goodbye” by saying “remember me”—shorthand for “remember me in your prayers.”6

This vision of a “house of prayer” is lost to us. At a recent gathering of pastors, I read the early church’s first job description for church leaders:

“Therefore, brothers, pick out from among you seven men of good repute, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we will appoint to this duty. But we will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.” (Acts 6:2-4; emphasis added)

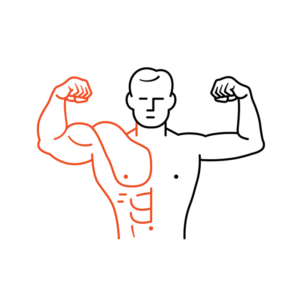

The job description is divided evenly between praying and preaching. So forty-five minutes into my talk I asked, “How much training do you have in ministry of the word?”

“Hundreds of hours,” they answered.

“How much training do you have in prayer?” I asked.

One pastor shouted from the back, “About forty-five minutes!”

Then I showed them this illustration. “Do we look like this man?”

In summary, prayer is not a ministry of the church—it is the heart of ministry through which the real, functional leadership of the economic union of the Spirit and Jesus, formed at the resurrection, operate. The pastor’s primary task is to be a praying pastor who facilitates a praying church. So what does a praying community look like? Let me give you several case studies interspersed with seven principles of beginning a praying community.

Discovering a Praying Church

1) You Learn to Pray by Praying

After Dad’s visit to L’Abri, he realized how prayerless his ministry was. He was particularly bothered that in the churches he’d pastored, prayer meetings had floundered. He wondered, “Who killed the prayer meeting?” Then he realized, “I killed the prayer meeting!”7 How? By talking too much. In other words, his unbalanced training (study of the word but not study of prayer) led to good teaching eating up space for good praying. So, Dad began to pray at prayer meetings!

Starting to pray isn’t much different from throwing a soccer ball out to a bunch of people who’ve never played soccer before, telling them the rules, and then saying “go play.” It’s a mess! You need to endure, to push through that early stage of floundering to learn how to pray together.

2) Begin Everything with Prayer

In the fall of 1970, we saw the Spirit begin to move in new ways. Revival broke out in our little church. Prayer meetings and Bible studies were jammed with hippies, drug addicts, and all sorts of people. Then in 1973, when Dad started New Life Church, he began with prayer. First the prayer meeting, then the church. For the next twenty years, the heart of the church was a four-hour weekly prayer meeting, which was led by the pastors, but anyone could attend. That was the engine that drove a sustained renewal that lasted over fifteen years.

So before you launch something, take time to ask God for wisdom, grace, and humilty. If I have concerns about a staff member, I will quietly begin to pray for them—sometimes for months—before I speak to them. Often, I see God begin to do things without me saying anything.

3) Praying As a Community Decenters Us and Makes Space for the Spirit of Jesus to Lead

Dad’s decision to pray at prayer meetings was the outworking of his realization that the Spirit, not his teaching or ministry, was at the center of the church. He decreased so that the Spirit, who brings us the risen Christ, could increase.

4) The Spirit Works “Outside the Box” of Mere Management, of What Is Humanly Possible

So what happens when you pray as a community? If I had to summarize it in one word, I’d say “surprise.” Unexpected things happen. Paul mentions this as he closes his prayer in Ephesians: “Now to him who is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, according to the power at work within us…” (Eph. 3:20).

One evening in 1973 at a local church, Dad said, “The gospel can change anyone.” After a psychiatrist in the congregation challenged Dad, he went home wondering, “Do I really believe the gospel can change anyone?” He decided to find the toughest people in Philadelphia to see if the gospel could change them.

And who was tougher than the Warlocks motorcycle gang? He knew they hung out at a local ice cream stand, so he went there with one of his seminary students. He bought an ice cream cone and walked over to a gang of rowdy teenagers who regularly gathered there to drink and share drugs.

With ice cream dripping down his hand, Dad gave one of his memorable opening lines, “I’m Reverend Miller. Are there any Warlocks here?” When they started taunting him, Dad made it worse by saying, “Actually, I’m Dr. Miller.” Just as the mocking was increasing, a tough-looking redhead—a thief, drug addict, and an alcoholic—said to the gang, “Shut up. I know this guy. He picked me up hitchhiking. We should listen to him.”

His name was Bob Heppe. Over the next six months, Dad befriended Bob, even listening to his drunken calls in the middle of the night. Dad patiently pointed Bob back again and again to Christ. Bob now serves as a missionary to South Asians in London.

5) The Community Orbits around Its Prayer Meetings

At my own ministry, “seeJesus,” the life of our mission orbits around our prayer meetings. We have three prayer meetings a week for our twenty-five staff members: thirty minutes on Monday and Wednesday, an hour on Thursday, and two hours on Friday. That comes to four hours of prayer each week. It’s open-mic time for the first fifteen minutes, when anyone can ask prayer for anything, and then we get into the work of prayer. Those meetings are the center of our life together. It’s where individual burdens become everyone’s burdens.

A kind of divine community forms around so much time in concentrated prayer. We are all aware that the Spirit is the One who does all the big things (and many of the small ones) in our work. So corporately, we are frequently celebrating surprise—the unexpected activity of the Spirit.

6) Think and Coach the Prayer Meeting

Because prayer feels spiritual, as opposed to concrete, we tend not to improve in our praying skills the way we would in writing or soccer. Since it’s “the Spirit,” it is supposed to just flow naturally, but there is so much to learn about praying together. Here are some of the problems of prayer meetings:

- People jump around from topic to topic, not paying attention to one another’s prayers.

- People pray only for felt needs, such as medical problems.

- Oversharing of prayer requests results in too little time to pray.

- Some key people don’t attend prayer time. You feel like you are all alone.

I’m not shy about coaching our prayer meetings, suggesting ways we can pray together more effectively. It’s taken time for us to not just have a jumble of prayer requests, but to listen to one another as we pray and build on one another’s prayers—almost like a conversation.

7) Praying Together Reenacts the Dying and Rising of Jesus

This last point is the most important: praying together is powerful because it reenacts the dying and rising of Jesus. First, the dying. I began to pray regularly for my family twenty-five years ago because I realized that my parenting wasn’t creating Christ in them. I had failed. My sense of my own weakness over the next ten years grew as God took me through relentless suffering. When I started seeJesus, I was weak in every area of my life. Now, nineteen years later, we are still underfunded, understaffed, and overwhelmed. Taking four hours out of the work week to pray weakens us even more because it gives us less time to work!

But we pray because we are weak. We don’t get stuck in weakness, however, because weakness is the launchpad for resurrection power. That’s Paul’s point in 1 Corinthians 1–2. The Corinthians are doing church badly, because they don’t realize that their weakness reenacts the dying of Christ, which leaves space for the Spirit to do wonders in their midst. Dying is the launchpad for rising. When Paul mentions the Spirit, he always mentions one of these five words: power, life, hope, knowledge, and glory.8 The Spirit brings power and wisdom, which creates new life and glory, filling us with hope.

In our little mission, we experience these real-time resurrections from the Spirit almost continuously. We’ve seen God work in so many ways that we are all aware the Spirit is at the center, working in response to our prayers to the Father. When you are aware of this as a praying community, it fuels itself. Answered prayer creates faith, which in turn encourages more prayer.

That’s why Paul and Silas prayed and sang in prison. They were anticipating and reenacting the resurrection of Jesus. The Spirit worked through the earthquake, overturning the false narrative of Paul and Silas as troublemakers. Their little praying community first transformed the prison and then impacted the whole city of Philippi. They didn’t just survive in a world where they had become powerless; God went beyond all that they could ask or think.

Paul E. Miller is founder and executive director of seeJesus, a global discipleship mission active in over thirty countries. He has released four books on the ministry’s core themes of Jesus, love, and prayer.

- Edith Schaeffer, Common Sense Christian Living (Nashville: Nelson, 1983), 205.

- Geerhardus Vos, Pauline Eschatology (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1994), 136–71.

- I’ve revised “spiritual” to “Spiritual” because Paul doesn’t mean “spiritual” in the sense of being religious or praying easily; he means we are “in step with” the Spirit or “led by” the Spirit. We are “of the” Spirit, possessed and controlled by him. A small “s” depersonalizes the Spirit.

- “Christ (as incarnate) experiences a spiritual qualification and transformation so thorough and an endowment with the Spirit so complete that as a result they can now be equated. This unprecedented possession of the Spirit and the accompanying change in Christ result in a unity so close that not only can it be said simply that the Spirit makes alive, but also that Christ as Spirit makes alive. Specifically, this identity is economic or functional, in terms of their activity.” Richard B. Gaffin Jr., Resurrection and Redemption: A Study in Paul’s Soteriology (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1987).

- “The life-giving activity predicated of the resurrected Christ is not predicated directly; the Spirit is an absolutely indispensable factor. Only by virtue of the functional identity of the Spirit and Christ, effected redemptive-historically in his resurrection, is Christ the communicator of life.” Gaffin, 89.

- Peter Brown, The Ransom of the Soul (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 40.

- C. John Miller, Outgrowing the Ingrown Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), 94–106.

- Gaffin, 68–70. I added “hope” and “knowledge” to Gaffin’s “power, life, and glory.”