Introduction

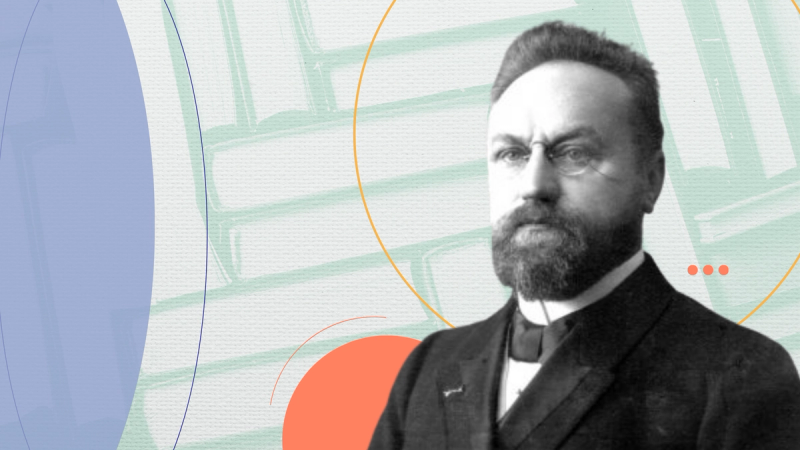

Herman Bavinck (1854–1921) was a theologian and pastor who developed a robust reformed theology and worldview that was applied in the various spheres of life, whether in the pulpit, in academia, art, education, politics and society. Due to the Trinitarian foundation of his reformed confessionalism, Bavinck taught a practical theology where Reformed dogmatics was taught in conjunction with Reformed ethics. According to Bavinck:

In dogmatics we are concerned with what God does for us and in us. In dogmatics God is everything. Dogmatics is a word from God to us, coming from outside us and above us; we are passive, listening, and opening ourselves to being directed by God. In ethics, we are interested in the question of what it is that God now expects of us when he does his work in us. What do we do for him? Here we are active, precisely because of and on the grounds of God’s deeds in us; we sing psalms in thanks and praise to God. In dogmatics, God descends to us; in ethics, we ascend to God. In dogmatics, he is ours; in ethics, we are his. In dogmatics, we know we shall see his face; in ethics, his name will be written on our foreheads (Rev. 22:4). Dogmatics proceeds from God; ethics returns to God. In dogmatics, God loves us; in ethics, therefore, we love him.

He teaches us something very important: it is not possible to study, develop and apply the doctrines of grace if we do not reflect God’s grace in everything we do. Therefore, it is the thesis of this brief article that, according to Bavinck, pride has no place for those who study and teach a theology that reflects the amazing grace of God; that is why there is no reformed theology apart from reformed ethics. In other words, poor ethics is often the outflow of a poor theology.

So, what did Bavinck teach his students about this topic? In his class notes discovered in 2008—later published in 2019 as Reformed Ethics—we find Bavinck addressing the issue of pride, its consequences, and its solution in several places. I will briefly develop some of these points here.

On Pride and the Fall

After elaborating on the profound nature of humanity being created in the image of God, Bavinck delves into the tragic reality of humanity under the dominion of sin. He traces this downfall back to the very first act of disobedience. Motivated by pride, Eve not only committed the initial sin but also denied its existence and its dire consequences. Adam and Eve’s sin involved two movements. On the one hand, sin led them to turn away from God and to enmity and hatred against God. On the other hand, sin led them to turn to self, resulting in “selfishness—a love of something other than God, namely, oneself; deification of self, glorification of self, adoration of self.”

In the first sinful act committed by Adam and Eve—and in every sin committed thereafter—there is “deification of oneself, glorification of oneself and adoration of oneself.” Isn’t that an expression of how horrible pride is? The descriptions of sin and pride bear great resemblance. For Bavinck,

Sin consists concretely in placing a substitute on the throne. That substitute is not another creature in general, not even the neighbor, but the human self, the “ego” or “I.” The organizing principle of sin is self-glorification, self-divination; stated more broadly: self-love or egocentricity. A person wants to be an “I,” either without, next to, or in the place of God. Turning away from God is simultaneously a turning to self. Prior to this, God was the center of all human thought and action; now it is the person’s “I.” Humanity not only surrendered its true center but also replaced it with a false center.

Accordingly, self-worship is an essential aspect of sin: “although this may not be conscious to the sinner, sin often proceeds from egocentricity, from the desire to exalt oneself.” For Bavinck,

the sin of pride, which is the naked expression of the principle of egocentricity, boasts of knowledge and virtue and develops into spiritual pride; it then progresses beyond egocentricity into terrible hatred of God, into intentional blasphemy, cursing, conscious hatred of God, and into delighting in this. All these spiritual sins as well are forms of egocentricity. Hatred against humanity and against God is provoked, wounded egocentricity.”

One of the greatest hindrances to the development of Reformed theology in churches is spiritual pride. When we learn, preach, and teach about God’s sovereign grace with a proud heart, we reveal a desire to assert our own sovereignty over God’s grace. This sin leads us to despise both God and our neighbors. Spiritual pride fosters arrogance, haughtiness, lawlessness, licentiousness, boasting, a craving for fame or honor, and ingratitude.

This should lead us to reflect seriously on the intention and the way we learn, apply, and teach the precious doctrines of grace. We cannot grow to the glory of God if we fail to recognize the urgent need to mortify pride, which undermines the relationship between theology and practice, and doctrine and ethics. It is a terrible contradiction to teach a theology that should lead us to humility, but to elevate ourselves above others and God. It is spiritual pride that leads one to the misuse of reformed doctrines, promoting division among those who should be united in truth. This is what led Bavinck to reflect on how much is still lacking in practice in the Christian confession. “Those who confess Jesus Christ, in particular to the members of our [Reformed] Church, a lesson must be kept in mind: do not be arrogant. . . be clothed with humility.”

The Example of Philippians 2:5-8

Our greatest example of this practice is the Lord Jesus Christ. Philippians 2:5-8 is pivotal in this respect because it presents Jesus as the ultimate model of humility. In these verses, Paul exhorts believers to have the same mindset as Christ, emphasizing that true understanding and practice of theology necessitates a corresponding ethical transformation. Without humility, our theology becomes disconnected from the grace it seeks to expound.

Paul begins this passage with a direct appeal: “Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 2:5, ESV). This verse establishes the foundation for Christian ethics—thinking and acting like Christ. The word “mind” here translates from the Greek phroneo, indicating an attitude or a way of thinking. Paul calls believers to adopt Christ’s selfless disposition, implying that theological understanding is incomplete without ethical conformity to the humility demonstrated by Jesus.

The mindset of Christ is one of voluntary humility and self-emptying. Jesus, being “in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped” (Philippians 2:6). This signifies that although Jesus was equal with God, he did not cling to his divine privileges. Instead, he chose to willingly assume a humble status. This act of kenosis, or self-emptying, underscores the essence of grace—unmerited favor that is extended without regard to status or entitlement.

Furthermore, Philippians 2:7 says that Jesus “emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.” The Greek word ekenosen (translated “emptied himself”) conveys the profound depth of Christ’s humility. It is crucial to understand that in taking on humanity and the role of a servant, Jesus did not lose or relinquish his divine nature or status. Rather, his humility was additive, not subtractive; he took on human nature in addition to his divine nature. As Chalcedon asserts, the distinction of natures in Christ is by no means taken away by the union, but rather, the property of each nature is preserved and concur in one person and one subsistence. About this, Bavinck writes,

Reformed theology stressed that it was the person of the Son who became flesh—not the substance [the underlying reality] but the subsistence [the particular being] of the Son assumed our nature. The unity of the two natures, despite the sharp distinction between them, is unalterably anchored in the person. As it does in the doctrine of the Trinity, of humanity in the image of God, and of the covenants, so here in the doctrine of Christ as well, the Reformed idea of conscious personal life as the fullest and highest life comes dramatically to the fore. . . All these developments in the doctrine of Christ are based on and occur within the boundaries of the Chalcedon symbol.

Thus, Christ’s incarnation involved the addition of a human nature without any diminution or change of His divinity.

The understanding of Christ’s incarnation and humiliation challenges us to reflect on our own attitudes. If the divine Son of God, in all His glory, willingly embraced human nature and servanthood, we are compelled to examine how pride and self-importance can obstruct our spiritual growth and theological integrity. The depth of Christ’s humility exemplifies the posture we must adopt in our lives and ministries. Just as Jesus took on the form of a servant, so must we adopt an attitude of servanthood in our theological pursuits and daily lives.

In Philippians 2:8, Paul further describes Christ’s humility: “And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.” The humility of Jesus is demonstrated in his obedience, culminating in the most humiliating and painful form of death—crucifixion. This ultimate act of humility and obedience shows the depth of Christ’s love and his commitment to God’s redemptive plan.

Therefore, our theological pursuits must be marked by a similar humility, recognizing that knowledge of God’s grace demands a corresponding ethical response. Pride and self-exaltation are antithetical to the doctrines of grace because they contradict the very nature of Christ, who, though divine, humbled Himself for the sake of humanity.

Moreover, the connection between theology and ethics, as highlighted by Bavinck, suggests that our understanding of grace should lead us to humble service and ethical living. A theology devoid of ethical implications is not truly reflective of the grace it claims to expound. Thus, a poor theology often results in poor ethics because it fails to grasp the transformative power of grace.

The appeal is clear: let us not be arrogant. Spiritual pride is destructive because it reflects what happened in the Fall. Pride can never be the beginning or the basis of our learning and teaching, otherwise it will be the beginning and the basis of our spiritual ruin. Humility is practical not merely theoretical. After all, Bavinck observes, “the purpose of ethics is that we grow in grace and not stay at the level of theory.”

Footnotes

Herman Bavinck, Reformed Ethics: Created, Fallen, and Converted Humanity, ed. John Bolt et al., vol. 1 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2019), 22.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol.1, 81.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol.1, 105.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol.1, 110.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol.1, 112.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol.1, 137-138.

BackBavinck, Kennis en Leven (Kampen: J.H. Kok, 1922), 78.

BackHerman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, vol. 3 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 259. Bavinck further affirms that “Chalcedon, accordingly, correctly pronounced that the union of the divine and the human nature in Christ was without division (ἀδιαιρετος) and without separation (ἀχωριστος). But over against the opposing school, it maintained with equal firmness that the union was without change (ἀτρεπτος) and without confusion (ἀσυγχυτος).” See Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, vol.3, 302.

BackBavinck, Reformed Ethics, vol. 1, 13-14.

Back