Some of my earliest impressions of Eve were shaped by C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In the world of Narnia, to be a “daughter of Eve” is simply to be human—not centaur or dwarf, fawn or talking animal. But to descend from Eve is also to have a royal destiny, to be a heroine who will rescue Narnia from the reign of the White Witch, from the chilled reality of always winter, never Christmas. I claimed the mantle “Daughter of Eve,” as I pictured myself enthroned with Queen Lucy the Valiant.

But a conflicting image also emerged. I learned to picture Eve like I was taught on the Sunday school flannel board: She stands before a wily snake, leaves strategically covering her nakedness and naivety. In my childish mind, Eve is more like Snow White than “the mother of all living,” and the snake takes the form of the beady-eyed witch, cloaked in black, her devilish smile hidden behind the glowing red apple she holds before the princess. The animated Snow White is my least favorite Disney princess. I observe neither courage nor passion; she has no adventure of her own, nor any real wit or depth. I wonder if Eve, like Snow White, is also flighty and easily deceived. Is this my feminine heritage?

These sketches morph and twist through the years. Eve is used in countless lessons to warn me of my propensities as a woman—to be deceived, to usurp, to covet, to fall (and lead) into temptation. We know little of Eve’s virtues, so I am mostly warned of her vices. We excavate her story for truth related to what it means to be a woman, and mostly, it doesn’t look good. My womanhood is dripping with power I must learn to suppress, lest I take the human race down with me.

Many women have walked this meandering path through womanhood’s biblical roots, navigating interpretations based more on the influence of art, literature, and the shifting tides of history and culture than the text itself. Stretching back centuries, biblical exegesis gets buried under layers of cultural bias, and we too are guilty of reading our experiences into the text, pointing to what we observe in our own time and place, and turning to Scripture to support our preconceived ideas. Mostly, we don’t do this vindictively—we hold sincerely to our biblical convictions. But it’s complicated. How do we identify and shed years of influence? How do we know what’s true when so many plausible possibilities have been offered? And what about when a proposed interpretation could deconstruct what we’ve always believed or threaten doctrines we consider foundational—our strongholds in the culture war, perhaps, or against the slippery slope of liberalism? These questions don’t have easy answers, but they are worth revisiting nonetheless. Eve and her descendants have been trapped in an identity crisis for far too long.

***

At the Heart of the Debate: Genesis 3:16

To the woman he said,

“I will make your pains in childbearing very severe;

with painful labor you will give birth to children.

Your desire will be for your husband,

and he will rule over you.” (NIV)

In evangelicalism, Genesis 3:16 rests at the center of debates regarding the role of women in the church, home, and society, and interpretations are often shaped by preconceived ideas about the nature of men and women and their roles. Of particular significance for the debates is the interpretation offered by Susan Foh. In the midst of second-wave feminism in 1975, Foh defined the woman’s “desire” in Genesis 3:16 as “a desire to possess or control [her husband] . . . to contend with him for leadership in their relationship.”[1] In her study of the Hebrew word translated desire (teshuqah)—which is found only in Genesis 3:16, 4:7, and Song of Songs 7:10—Foh uses etymology to build a semantic range for this rare word, arguing that cognate evidence supports desire having an adversarial nuance.[2]

She corroborates this proposal by drawing out the parallels between Genesis 3:16 and 4:7. In Hebrew, these verses are exactly parallel, except for changes in person and gender. As a result, Foh considers Genesis 4:7 the interpretive key to Genesis 3:16, despite the preference by other commentators throughout history to associate Genesis 3:16 with Song of Songs 7:10 since they both address male-female relationships.[3] She argues that the meaning in Genesis 4:7 is straightforward: “Sin’s desire is to enslave Cain—to possess or control him, but the Lord commands, urges Cain to overpower sin, to master it.”[4] According to Foh, this clarifies what is unclear in Genesis 3:16. Like sin, the woman desires to possess or control her husband. This has implications for the interpretation of the husband’s rule as well. Foh holds that the husband’s rule is positive, a necessary corrective to the woman’s attempt to usurp her husband’s authority. As Cain needs to master the sin seeking to destroy him, so the man “must rule over [the woman], if he can.”[5]

Her interpretation presented a solution to many conservative evangelicals searching for a way to respond to the feminist movement of the time. Feminism had infiltrated the church, causing many to question time-honored interpretations of passages involving manhood and womanhood, gender roles, and their implications within the church, home, and society.[6]

The impact of her interpretation has been far-reaching for evangelicals. Foh offered insight into the feminist movement, even arguing it made biblical sense. She isolated the cause—a woman’s inherent desire to usurp authority—and others applied her work, stressing submission for women and “biblical womanhood.”[7] Over forty years later, Foh’s view has become the standard interpretation of Genesis 3:16 by evangelical scholars.[8] It has even made its way into the ESV translation: What once read, “Your desire shall be for your husband,” now reads, “Your desire shall be contrary to your husband.”[9]

The fact that this argument is both polemical and biblical is what makes it complicated. Foh—and the complementarian pastors and theologians who have followed in her footsteps—have moved from reactivity to genuine conviction. She has persuaded many by her arguments, so much so that the arguments no longer need to be made. Primed by our cultural moment to believe they’re true, we read our revised Bible translation and don’t give it a second thought.

***

Why You Should Revisit Genesis 3:16

Though it would be easy to point to harmful applications of this take on Genesis 3:16, the fact is that implications are not the measure of truthfulness. But when exegesis is rooted in polemics, and its application leads to values and actions that contradict other portions of Scripture, perhaps it’s worth revisiting the text and asking ourselves honest questions about why we believe what we believe.

In the remainder of this essay, I would like to revisit Genesis 3:16 and see if it might be reimagined in a way that is more faithful to the text and more charitable of one another, and then consider what we, both men and women, can learn from both the process of reexamination and the implications for the church as we reclaim for women the mantle “Daughters of Eve.”

***

What’s in a Word?

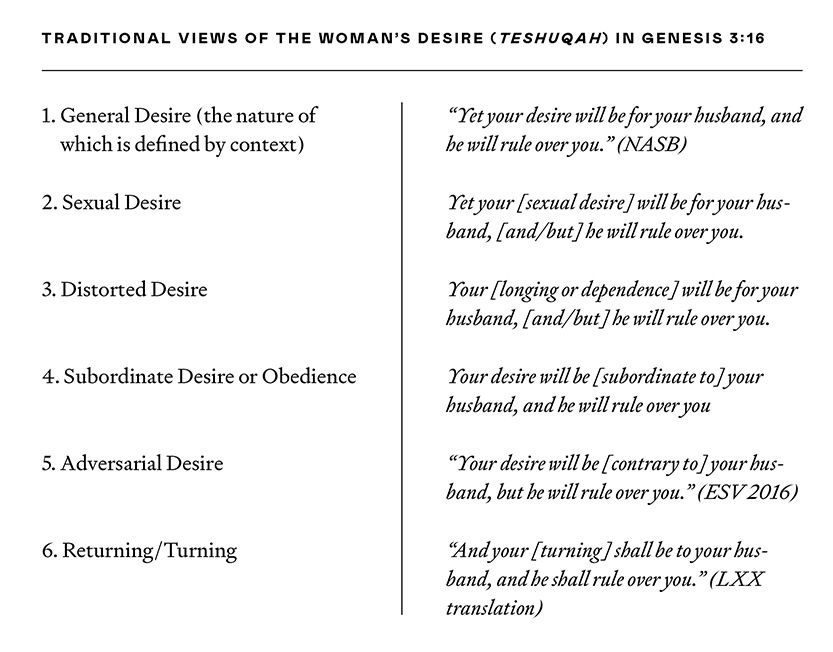

Foh’s suggestion for the nature of the woman’s desire is one among many. Though not exhaustive, the table below contains some of the prominent historical views for the meaning of teshuqah.[10]

How are we to evaluate these possibilities? Some see the desire as positive, and some negative. Each view has its proponents throughout history, its explanations for the relationship of desire to the other aspects of the verse, and its arguments from the surrounding context (and personal experience).

Recent studies on the cognates of teshuqah and its appearance in the Dead Sea Scrolls have cast considerable doubt on Foh’s etymological argument for an adversarial nuance.[11] Further, even the reading of Genesis 4:7, which appears to be quite clear in our English Bible translations, is actually rather difficult in Hebrew, in part due to its structure. Desire has a third-person masculine pronominal suffix, but its presumed antecedent, sin, is feminine. Scholars have explained this by seeing sin pictured as a (masculine) wild beast waiting to devour its prey.[12] This is what is reflected in most English translations. The Septuagint (LXX), however, places Abel as the antecedent of desire, with Cain’s right of primogeniture in view.[13] In other words, if Cain does what is right, the proper birth order will be restored. Whatever one’s reading of Genesis 4:7, it is not as clear as Foh and others have claimed it to be.[14]

Though Foh’s argument is rooted in etymology and in the verse’s parallels to Genesis 4:7, we simply can’t be sure about the nature of the woman’s desire based on these factors alone. The adversarial nuance is not embedded into teshuqah but must come from the context.

***

The Context of Covenant

Genesis is not just the foundation of “male and female he created them” (Gen. 1:27); it’s the foundation of the Bible, the starting point for the story of God’s redemption of all things in Christ. Before we get to Genesis 3, we must consider Genesis 1–2; and before we consider gender roles, we must consider covenant.

Covenant is “the very fabric of Scripture . . . God’s chosen framework for the Bible.”[15] This is not a framework imposed on Scripture, but one that arises from it; as Michael Horton explains, “It is not simply the concept of the covenant, but the concrete existence of God’s covenantal dealings in our history that provides the context within which we recognize the unity of Scripture amid its remarkable variety.”[16]

The Bible uses covenants to help us understand God’s dealings with his people, and this provides a framework for understanding redemptive history. The first few chapters in Genesis are instrumental in illuminating these concepts:

At creation, God commits himself to his creation to sustain them and be God to them. So also, being created in the image of God by necessity obligates Adam to God. . . . God’s creation generates a relationship with implicit obligations.[17]

God’s covenant with Adam at creation has obedience at its center. This is known as the covenant of works, “wherein life was promised to Adam; and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience” (WCF 7.2). True to covenantal form, alongside the promised life awaiting Adam, there is also a threatened curse for disobedience (Gen. 2:17). Note that though this covenant is with Adam, it has in mind “his posterity.” “As covenantal or federal head,” writes S. M. Baugh, “Adam acted on behalf of his whole race in the covenant of works.”[18]

Egalitarian scholarship rightly emphasizes man and woman’s equality at creation, seen in the initial account of creation in Genesis 1:26–28. Both the man and woman are created in God’s image (Gen. 1:26), blessed with the cultural mandate (Gen. 1:28), and given the earth for provision and stewardship (Gen. 1:29–30). However, though ontological equality and vocational partnership are undoubtedly celebrated in this text, headship is also embedded in the narrative.

In the second creation account, Adam is both the recipient of a royal commission to protect and keep the garden (Gen. 2:15) and entrusted with the command not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen. 2:16–17). Eve is given to him as his ezer kenegdo—his partner in the task (Gen. 2:18). This account establishes Adam’s headship, setting the stage for what will happen in the Fall. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil provides a testing ground for Adam, the Lord’s covenant servant. In this test, Adam stands as representative of the whole human race, and therein lies the main point of the text: in emphasizing Adam’s obedience, it sets the stage for redemptive history in presenting Adam as a type of Christ and in establishing the concept of the one for the many. Thus, as Jerome T. Walsh argues, a hierarchy is established in Genesis 2–3, with a chiastic center in Adam’s failure: “and he ate” (Gen. 3:6).[19] The text demonstrates that this is the moment of ultimate devastation, because when Adam fell, we all fell with him (Rom. 5:12).

As we turn more specifically to the context surrounding Genesis 3:16, this is what the text compels us to keep in mind: The context is covenant; the emphasis is obedience; the scope is corporate.

***

Removing Gendered Assumptions

If the primary purpose of the first few chapters of Genesis is to lay the foundation of covenant, then this has some initial, big-picture implications for debates about gender. Those who want to argue that headship finds its foundation in the Fall fail to address the creational foundation of headship, and they fail to connect the role of headship with redemption. Headship is not primarily about gender but about covenant. But for those of us who hold to an enduring principle of male headship in the church and home, there are implications for how the lesser offices of elder, husband, and father are shaped by Christ, our federal head. We have much to learn from the New Testament writers, who fostered a corporate identity, and who spoke of headship emphasizing love, humility, sacrifice, responsibility, and partnership (see, for example, Eph. 6:22–33; Phil. 4:3; 1 Pet. 5:1–3; Heb. 13:17).

More specifically, as we look at the narrative of the Fall (beginning in Gen. 3:1), this covenantal understanding helps us see what is happening in the text—a covenantal test of obedience—and what is not. Though we see in the Fall narrative that Satan is bent on upending God’s created order, this same motivation cannot be applied to Eve. The text indicates that by listening to the voice of the serpent, she has bought into the lie that she can be like God. The text does not indicate, however, that she refused to obey the voice of her husband (“who was with her,” 3:6), nor does it indicate a domineering pressure to coerce her husband into disobedience (“she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate,” 3:6). If the account of the Fall demonstrated Eve as a usurper of male authority, then it may justify Foh’s adversarial understanding of the woman’s desire; but any discussions about Eve’s motivations must be imported into the text, since neither here nor elsewhere in Scripture is the Fall characterized as Eve usurping Adam’s authority. In brief, the narrative does not characterize Eve as exalting herself above Adam, but rather “[exalting] herself above her Creator.”[20]

That doesn’t mean the text has nothing to say about the relational dynamics between Adam and Eve. Sin does fracture the couple’s love and unity, evidenced by their shame and separation over their newly realized nakedness (Gen 3:7). Meredith Kline calls the Fall the first divorce.[21] Adam’s words illustrate the conflict that will now characterize fallen relationships: “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate” (Gen. 3:12). But is the emphasis here their marriage, their different sexes, or their new, sin-tainted posture toward each other? Paul describes life prior to faith in Christ in terms of this relational dysfunction: “For we ourselves were once foolish, disobedient, led astray, slaves to various passions and pleasures, passing our days in malice and envy, hated by others and hating one another” (Titus 3:3). These sinful attitudes and behaviors do not discriminate on the basis of sex.[22] Further, if Genesis 3 intended to show that the woman possessed an inherent desire to usurp, then surely the rest of the biblical witness would attest to that. However, while there are examples of women who do usurp authority that is not rightfully theirs, there are also examples of men who do so.[23] The narratives throughout the rest of Genesis and the Old Testament do not demonstrate a battle of the sexes, but rather a battle between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent, often expressed through the conflict of brothers.[24]

Human beings were created to live in harmony with God and with one another, but sin disrupts these relationships. This is undoubtedly evidenced in the text, in the rest of Scripture, and in our own experiences. When we witness Adam and Eve hiding from God and pointing fingers at each other, we are meant to be grieved. How far they have fallen!

***

The Context of Curse?

After the climatic note, “and he ate,” Genesis 3:16 shows us what sin costs: it builds tension in the narrative, leading into what has traditionally been labeled “the curse.” For Foh and others, if the woman’s desire in Genesis 3:16 is construed as positive or compulsive, then it doesn’t make sense as a punishment. But perhaps we have too quickly labeled this section “the curse,” and so missed an important aspect of what’s happening at this point in the garden.

The curse section begins with a confrontation. The man and woman hear God’s approach and they hide (3:8). The reader knows that God has said, “In the day that you eat of [the tree of knowing good and evil] you shall surely die” (2:17). Adam and Eve are waiting with bated breath, knowing they have disobeyed God’s command, and with disobedience come covenant curses. God does indeed move on to judgment, but it’s not what we expect.

The Lord addresses each character in turn. Though his order has been corrupted, God reinstates it as he addresses each party, ending with Adam, the one ultimately held accountable. There are varying explanations for the structure of this curse narrative (vv. 14–19), but they all generally affirm the exclusive context of judgment, seeing the section as a list of punishments imposed by God as a result of the man and woman’s sin. These are summarized as follows: the serpent will crawl on his belly and eat dust (v. 14); there will be an enduring battle between the woman and the serpent (v. 15); women will experience pain in bearing children (v. 16ab); there will be trouble in marriage (v. 16cd); work will be difficult (v. 18-19a); and now there will be death (v. 19b). This death is seen as the fulfillment of God’s promised judgment in 2:17—most explain that God was speaking of immediate spiritual death in 2:17, with the new inevitability of physical death also resulting from sin. In surveying this long list of punishments, we can feel the heaviness of judgment, and as an etiology, it certainly serves to explain the difficult conditions of life in a fallen world. It’s understandable that Foh and others would conclude that whatever comes from these pronouncements must match the ugliness of sin that has entered the world.

But viewing the curse narrative only through the lens of judgment overlooks some key features of the text. First, only the serpent is cursed directly (“cursed are you” in v. 14; emphasis added). His is a curse to ultimate and eternal destruction, for him (Satan) and his seed. The woman and the man are impacted by the pronouncements of their sections, but never again does “cursed are you” appear in these verses.[25] This differentiates God’s treatment of the serpent from his treatment of Adam and Eve. Though the effects of their sin are devastating, they are temporal.[26] Though they should be relegated to the status of the serpent’s seed as covenant-breakers, instead they are placed in opposition to the serpent and kept as a royal line bearing the promise of restoration. God addresses his covenant-breakers with the promise of a new covenant: the covenant of grace. The proto-gospel of Genesis 3:15 promises a deliverer who will crush the serpent’s head. What’s more, that deliverer will come through the seed of the woman. This is astounding grace.

Second, the proper punishment would have been immediate death, both physical and spiritual. God warned Adam of such when he gave his prohibition, and there is no reason to think delayed death is what was intended (2:17). Rather, God graciously chose not to enforce the terms of his covenant. Joshua Van Ee writes,

It is best to say that God does not bring about the threatened judgment on the man and the woman. . . . The narrative is an example of God refraining from bringing the promised judgment as seen elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible.[27]

Instead of death, we see the continuation of life. There will be pain in childbearing, but the woman will continue to bring forth children. There will be thorns and thistles, but the ground will continue to bear fruit. Despite the continued rebellion of the human race, God will continue to sustain life until the appointed time, so that he can accomplish his plan of redemption. This, again, is astounding grace.

Third, Adam responds to the curse narrative with faith. Kline writes, “Adam in effect declared his confessional ‘Amen’ to the Genesis 3:15 promise of restoration from death to life through the woman’s seed. This he did by naming the woman ‘Life’ (Eve).”[28] Kline specifies Genesis 3:15 as the expression of God’s grace through the proclamation of the gospel to which Adam and Eve respond in faith, but this declaration comes after the rest of the curse narrative. It’s certainly a response to 3:15, but what precludes it from being a response to the whole experience of God’s mercy—the delay of death, the hope of continued life and provision, and his promise of a deliverer? Each of these components of life after the Fall are an act of God’s grace, to which Adam responds, “Amen!”[29]

Thus, while judgment does occur for sin, this section is characterized as much (if not more so) by grace. Rather than listing punishments, a more effective structure of verses 14–19 might be to view each section as containing both curse and continuity.

***

Curse or Continuity?

So where do the woman’s desire and the husband’s rule fit? Are they curse or continuity? I suggest the following four reasons that the woman’s desire and the husband’s rule should be considered among the “continuity” theme of the curse narrative: First, the structure of each section supports it. The curse affecting both the man and the woman are marked by pain (vv. 16–17). What follows the pain is what continues—producing children (v. 16) and food (v. 17). What follows next demonstrates how this will continue: through the continued creation ordinances of marriage (v. 16; see Gen 2:24) and work (v. 19; see Gen 2:15).[30]

Second, the husband’s rule does not necessarily mean a harsh rule. The word for rule, mashal, is used for both benevolent and oppressive rule throughout Scripture, with its particular nuance determined by the context. There is no reason this phrase cannot be the continuation of Adam’s headship in marriage as God originally designed it. Third, this act of God’s grace and mercy is the only way to explain the gap between Genesis 3:12 (“The woman whom you gave to be with me”) and Genesis 4:1 (“Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain”). Apart from God’s act of restoring the man and woman to each other, what would keep them from remaining alienated?

Finally, the rest of Genesis (and the Scriptures) supports it. The remainder of the book of Genesis fleshes out themes contained within the curse narrative. As early as 4:1, we see that marriage has in fact continued and brought about new life. Eve gives birth to warring seeds (brothers), which will continue to battle each other throughout Scripture. There is much difficulty in childbearing, including struggles with infertility (see Gen. 16:1, for example) and even death after difficult labor (Gen. 35:16–19). The curse of the ground is also evidenced by famine (see Gen. 12:10; 26:1; 41). Further, God’s covenant terms relate specifically to these themes, which then stretch throughout the rest of Scripture. God’s promise to Abraham includes countless offspring, through whom the promised seed would come, and an abundant land filled with blessing. The blessings and curses of the Mosaic covenant are later expressed in these terms. The original purposes God gives to the man and woman (to “work the garden and keep it,” and to “be fruitful and multiply”) are both frustrated as a result of sin, allowed to continue by God’s gracious act, and then become components of God’s promises to his people (now he will make them fruitful and multiply them, and he will give them a fruitful land as an inheritance). Notably absent are usurping wives and domineering husbands. Though Scripture describes both marital conflict and sinful characters, these are not caricatures of gendered propensities but rather illustrations of the reality of sin’s impact on human relationships. The alleged adversarial desire of Genesis 3:16 does not mark a motif that will continue to play out.

If we take all of this into account—the meaning of desire and rule, the context of covenant, restoration, and mercy—then there is reason to argue that the woman’s desire in Genesis 3:16 is for marriage. By an act of God’s gracious continuity, God restores the creation ordinance of marriage after the Fall, sustaining what sociologists point to as a critical stabilizing institution of society. Though marriage is not immune from attack and distortion, the fact that believers and unbelievers alike can continue to marry and exist in healthy relationships despite our fallenness is explicable only by God’s common grace.

***

Restoring Eve

My hope in reexamining this passage is not to impose different culturally informed biases onto the text, but rather to bring us back to the biblical context, to see the role of these Genesis chapters in not only shaping our views of men and women but also in shaping our understanding of God’s covenant dealings with his people and his plan for the redemption of his fallen image-bearers. Certainly, the creation account speaks to God’s creation of male and female, a reality that’s under attack in our time and place. But in an attempt to counteract the secular cultural views on sex and gender, have we unwittingly read into Scripture views of the same that aren’t there?

I’m persuaded that the creation account establishes male headship that carries through to the church and home today, a principle that has been largely discarded outside of complementarian circles and practiced poorly within them.

But if Genesis 3:16 rests in a narrative that highlights God’s grace and mercy, rather than establishing gender-based suspicion of one another, then perhaps our conversations about men and women could shift away from concerns about power and control to love, service, partnership, and responsibility. Perhaps we could lay down our arms in the battle of the sexes and tell the truth about our sinful inclinations without having to assign them to a particular sex. Just as God restored Eve to her rightful place at Adam’s side, allowing for life and redemption to continue, perhaps we could restore the daughters of Eve within the church, recognizing them not as threats, but as partners in the gospel.

Kendra Dahl (MA, Westminster Seminary California) is director of content for Core Christianity and White Horse Inn.

2. Foh, “Desire,” 378.

3. See, for example, A. A. Macintosh, “The Meaning of Hebrew תשוקה,” Journal of Semitic Studies 61, no. 2 (Autumn 2016): 366.

4. Foh, “Desire,” 380–81.

5. Many complementarian theologians depart from Foh on this point. The Danvers statement, for example, sees the distortion of both man’s and woman’s roles as the result of the Fall. Further, much of the work done to combat Foh’s adversarial desire interpretation lands on the other extreme, suggesting that the woman’s desire is positive while the husband’s rule is now harsh and abusive.

6. Foh, “Desire,” 376. Foh herself points to this reexamination as the impetus for her work. She writes, “The current issue of feminism in the church has provoked the reexamination of the scriptural passages that deal with the relationship of the man and the woman.”

7. See John Piper and Wayne Grudem, eds., Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2006).

8. Janson C. Condren, “Toward a Purge of the Battle of the Sexes and ‘Return’ for the Original Meaning of Genesis 3:16b,” JETS 60, no. 2 (2017): 227–45, collects a list of scholars and pastors who espouse Foh’s view.

9. Upon announcing this change, the publisher announced that the ESV was closed to further changes (https://web.archive.org/web/20160820002244/http://www.esv.org/about/pt-changes/), a move that was later reversed (https://www.crossway.org/articles/crossway-statement-on-the-esv-bible-text/).

10. For a fuller explanation and analysis of each of these traditional views, etymology, and Foh’s interpretation of Genesis 3:16, see my unpublished paper “The Woman’s Desire as Gracious Continuity: An Analysis of Susan Foh’s Interpretation of Genesis 3:16 and an Alternate Proposal,” April 2021, https://www.academia.edu/s/2cb27b2d4f?source=link.

11. See my paper for a collection and summary of this scholarship.

12. R. P. Gordon, “‘Couch’ or ‘Crouch’? Genesis 4:7 and the Temptation of Cain,” in J. K. Aitken, K. J. Dell, and B. A. Mastin, eds., On Stone and Scroll: Essays in Honour of Graham Ivor Davies (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 195–209. Referenced in Macintosh, “The Meaning of Hebrew תשוקה,” 372.

13. Adam Clarke, Commentary on the Holy Bible (Kansas City, MO: Beacon Hill Press, 1967), 59.

14. Foh, “Desire,” 383, does state why she sees sin’s desire in view versus Abel’s in “Desire,” 380n21, but her claim that “the interpretation of 4:7b is clearer” fails to account for the historical difficulties in interpretation.

15. Michael Brown and Zach Keele, Sacred Bond (Grandville: Reformed Fellowship, 2012), 11.

16. Michael Horton, Introducing Covenant Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2009), 13.

17. Brown and Keele, Sacred Bond, 43.

18. S. M. Baugh, “Covenant Theology Illustrated: Romans 5 on the Federal Headship of Adam and Christ,” Modern Reformation 9, no. 4 (July/August 2000), 18 (emphasis original).

19. Jerome T. Walsh, “Genesis 2:4b–3:24: A Synchronic Approach,” JBL 96, no. 2 (1977), 161–77.

20. Irvin A. Busenitz, “Woman’s Desire for Man: Genesis 3:16 Reconsidered,” Grace Theological Journal 7, no. 2 (1986): 208.

21. Meredith Kline, Kingdom Prologue (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 130.

22. Someone may argue that Paul’s instructions to husbands and wives aim at gendered propensities. However, as Busenitz observes (208), NT commands to submit to authority are directed not only to wives but also to children, citizens, members of the church, younger men, etc. These commands are related to propensities inherent to a particular role. Because of sin’s impact, the one in authority needs to be reminded to be loving and gentle; the one under authority needs to be reminded to humbly submit.

23. Consider the “evil queens” of Israel’s history, Jezebel and Athalia. Consider also Jeroboam’s rebellion, leading to the northern tribe’s separation from Judah.

24. Consider Cain and Abel, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau. Joseph and his brothers are a further expression of relational conflict, though not representing opposing seeds. Likewise, though generally secondary to the theme of warring seeds, we also see woman-to-woman conflict, as in Sarah toward Hagar and Rachel and Leah. This is not to suggest that there is not abuse and oppressive rule evidenced in the narrative (consider Dinah and Tamar, for example). But we must question if the text aims to present gendered tendencies or the reality of a sin-tainted world, where conflict, exploitation, abuse, and rebellion abound, regardless of gender.

25. This is in stark contrast to God’s response to Cain in Gen. 4:11, where he again says, “cursed are you,” identifying Cain as the seed of the serpent.

26. Kline, Kingdom Prologue, 136.

27. Joshua Van Ee, “Death and the Garden: An Examination of Original Immortality, Vegetarianism, and Animal Peace in the Hebrew Bible and Mesopotamia” (PhD diss., University of California, San Diego, 2013), 170. He gives the following as examples: “the interpretation of Micah’s prophecy (3:12) in Jer 26:18-19, God’s statement in Ezek 33:14-15, and Jonah’s complaint in Jonah 4:2.”

28. Kline, Kingdom Prologue, 149.

29. God’s provision of clothing for Adam and Eve is further evidence of the graciousness and restoration characterizing this section (2:21).

30. Man’s returning to dust is another aspect of the curse narrative with which I have not dealt in detail here. Though it has always been taken as the promised punishment of death, there is a gracious element to it as well. God will not allow man to continue in his sinful state perpetually. Whether or not resurrection is in view in Gen. 3:19 requires further study, but passages such as Isa. 26:19, Job 19:25–26, and Paul’s discussion of resurrection in 1 Cor. 15:35–49 may shed helpful light. Death is referred to as the last enemy to be defeated (1 Cor. 15:26), and Revelation ironically speaks of the first resurrection when it means the death of the believer. Thus, though death is the result of sin, it is also the entrance into new life—the ultimate restoration to which God is pointing in his pronouncement of the effects of sin in Gen. 3:14–19.