Over the past few years, I have dabbled in collecting vinyl records, or LPs. Recently, I decided to upgrade my turntable and purchase a system with stereo speakers. I now have one on the right and one on the left, and the sound is warm and inviting. It has been a terrific upgrade to my study. The neat thing about stereo speakers is that if you get up close to them one at a time, you’ll notice they’re playing different things. For example, the speaker on the left might have most of the electric guitar, and the one on the right might have more of the keyboards. But no matter the differences, the reality is that both speakers are playing the same song.

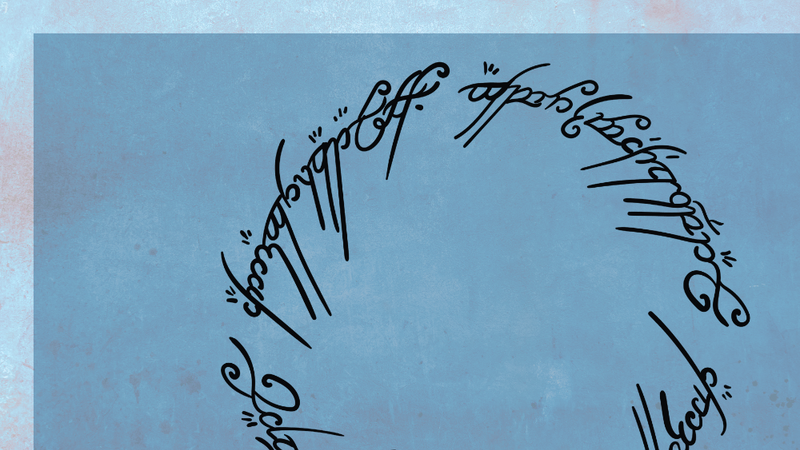

This essay is titled “Sirens in Stereo,” and that is what I mean by “stereo.” In our particularly fraught and polarized society, it can feel as though we’re constantly assaulted by competing messages, marketing, and ideologies from two opposing directions: from the Left and from the Right. “Sirens” is not a reference to the blaring noise you hear from an emergency vehicle. A Siren is a creature in Greek mythology, made most famous by Homer in The Odyssey. Odysseus and his men sail past an island where Sirens, creatures with unimaginably beautiful voices, sing to entice sailors to shipwreck and death. Odysseus has his men stuff beeswax into their ears, but he goes without ear protection; he wants to hear the Siren song. He has his crew tie him to the mast, with an exhortation not to untie him, no matter what he says while under the spell.

This is all a metaphor, then, by which I mean that our contemporary culture wars are increasingly “Sirens in Stereo.” Alluring voices from opposite directions entice us to embrace worldviews and ideologies that ultimately will leave us shipwrecked. From the Left, the challenge ought to be familiar enough: an ascendant cultural Marxism that views traditions, historic norms, and long-standing institutions as toxic enablers and perpetuators of injustice that must be razed to the ground so that a new age of peace and harmony can emerge from the ashes.

A number of reactionary movements have emerged on the Right that seem to sing a different tune—an opposite one, in fact. Whatever the “other side” is for, they are against. But on a closer listen, one discovers, much as one might with a stereo system, that they are actually playing the same song. They, too, wish to tear down traditions, norms, and institutions so that their version of utopia might emerge.

If the metaphor of Sirens in Stereo is to hold, however, there must be a “middle.” Odysseus had a ship to protect from the Siren song; what should we protect or preserve? In other words, if two opposite extremes are squeezing or pressing in on something, just what is that thing?

Classical Liberalism

That thing is “Liberalism.” When I was growing up, “Liberal” was the word used for what are now called “Progressives.” I do not mean that kind of “Liberalism.” What I mean is something more generally called “classical liberalism,” which has much more in common with historic American conservatism than Progressivism.

Classical liberalism is notoriously difficult to define. Understood in its broadest scope, it is the political system of ordered liberty that has prevailed in the Western world for the past three hundred years. It is a complex of mutually reinforcing ideas that includes commitment to individual equality before the law, representative government, private property rights, and wide freedoms of economic exchange, speech, religion, and association—all of which produce a robust civil society or “private sector” and a limited state. The emergence and global influence of this tradition (nowhere more profoundly seen than in the American founding) has produced unprecedented global prosperity and improvement to quality of life by nearly every measurable statistic. There is nevertheless no shortage of academics, intellectuals, and politicians who, for varying reasons, decry this way of organizing society. Left-wing collectivists have always found Liberalism inconvenient to their totalizing political aims, but now voices on the Right are joining the chorus.

I wish to suggest that the classically liberal order—while certainly not perfect and, indeed, a continuing work in progress—ought to be defended not simply because it works but because it is a hard-fought and hard-won fruit of the Christian religion. Since there isn’t room here for a full treatment, consider historian Tom Holland’s critically acclaimed book Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. In it, he argues that our notions of individual liberty, freedom of conscience, equality under the law, the idea that each human being has equal dignity, and many other things besides are provided specifically and exclusively by Christianity. These notions did not exist in antiquity, and they were not the inventions of Enlightenment philosophy. It was the advent of Jesus Christ that brought about this great revolution in humanity’s understanding of itself and the world.

He is not alone in noticing. In 1933, Westminster Theological Seminary founder J. Gresham Machen was alarmed by the “blatant and extreme” attack on civil and religious liberty represented by Russian Communism and Italian Fascism. More worrisome, however, was that these totalitarian impulses were being found right here at home. He lamented what he called the “machine”—the relentless growth of the paternal state, the centralization of its power, bureaucratic standardization and control, and the “tyranny of the expert.” He was particularly worried that this involved the erosion of other important institutions of a free civil society. Machen lamented that liberty had begun to fall out of favor:

Yet despised though liberty is, there are still those who love it; and unless their love of it can be eradicated from their unprogressive souls, they will never be able to agree, in their estimate of the modern age, with those who do not love it.

To those lovers of civil and religious liberty I confess that I belong; in fact, civil and religious liberty seems to me to be more valuable than any other earthly thing—than any other thing short of the truer and profounder liberty which only God can give.

We are thus in good company in loving and wishing to preserve the civic and political system of classical liberalism and to defend it against its detractors: with both Progressives on the Left and so-called Post-Liberals on the Right. They are singing a song in stereo.

The New Nationalism

The Progressive Left has long been Post-Liberal. Progressivism’s American political founding father was President Woodrow Wilson, who lamented the US Constitution. It was an archaic and useless hindrance to the implementation of an all-encompassing state that would order society according to “scientific” methods. But there are today self-styled “conservatives” who also think the American founding was a mistake, and that those who defend and champion classical liberalism are naive and outdated relics of the past. These are “Post-Liberals,” and they exist in a variety of permutations: National Conservatives, Roman Catholic “Integralists,” and Christian Nationalists. These all believe that the basic principle that government exists to protect natural, intrinsic, God-given rights—that is, to protect individual liberty in an ordered space in which one might pursue happiness or blessing or flourishing—is mistaken.

For them, government exists to define and to shepherd society toward the “common good.” It does not just protect the liberty of people to pursue some desired end; it protects liberty only insofar as it is used toward the end that it approves. The government first dictates what “happiness and blessing and flourishing” are and then protects your right to pursue that happiness, provided you have the requisite stamps on your government paperwork, so to speak.

If that sounds like a strange brand of conservatism, it should. It is usually Progressives who are intolerant of all the structural barriers to ushering in their vision of the “common good,” their fantastical utopia of total equality or “equity” where the government provides for every need from cradle to grave and nobody has to suffer the indignity of being referred to by a wrong pronoun. Progressives don’t like the fact that our system doesn’t allow small majorities to lord it over minorities—hence, things like the Electoral College and the Senate filibuster have to go! The Supreme Court must be expanded! Get these impediments out of the way so that we can use government coercion to usher in our vision of the common good: to reward our progressive friends and organizations and corporations that are committed to “right-think” and punish and hound out of polite society our bigoted enemies. The people cannot be allowed the liberty to define what is good, because the people do not know what is good for them. They need the state, with its wise central planners and philosopher-kings, to “perfect their natures.”

It may sound different coming out of the right-hand speaker, but Post-Liberals are playing the same song. Post-Liberal advocate Sohrab Ahmari writes that he wants “to fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” He, too, has a gleaming utopian vision. A senior editor for an extremely popular right-wing website wrote: “The government will have to become, in the hands of conservatives, an instrument of renewal in American life—and in some cases, a blunt instrument indeed.”

“Blunt instrument” means a vast expansion of government power and coercion. He then considers:

To those who worry that power corrupts, and that once the right seizes power it too will be corrupted, they certainly have a point. If conservatives manage to save the country and rebuild our institutions, will they ever relinquish power and go the way of Cincinnatus? It is a fair question, and we should attend to it with care after we have won the war.

Anyone familiar with history ought to know that every tinpot dictator from Robespierre to the present has said precisely this. Trust us. We’ve got to break a few rules to save the nation. We’ll relinquish all this power once we’ve won. Pinky promise.

Progressives and Post-Liberals alike hate the constraints. Both desire the state to enact, by coercion and force of law, their vision of the good. What they want is power—the very thing the American founders so wisely, self-consciously, and aggressively diffused throughout multiple and layered institutions (i.e., local, state, and federal) with checks and balances, three branches of government, a bicameral legislature, and so forth, all underwritten by a constitution designed to shackle the government to very limited spheres of influence. The system was designed to keep hotheads from rewarding their friends and punishing their enemies, to keep small factions from imposing their will on others, and to keep even small majorities from lording it over minorities.

The ironic and extremely telling thing is that both Progressives and Post-Liberals have convinced themselves that the American system of classical liberalism gives the other side an unfair advantage. The Progressives lament all the structural roadblocks: A constitutional amendment? What a hassle! The Post-Liberals lament liberty itself (“individual autonomy,” they derisively label it) because by means of that liberty, some people live badly and convince others to live badly, and it has been by means of that liberty the Left has taken a long and astonishingly effective “march through the institutions.” Progressives think law keeps them from winning. Post-Liberals think liberty keeps them from winning. That speaks to the marvel of the American experiment: it leaves all power-hungry narcissists unfulfilled.

Progressives have always been unapologetic about their desire to tear down the thickets and hedges of constitutional law so as to wield unencumbered the levers of power. Conservatives have always unapologetically championed individual liberty and cherished those thickets and hedges of protection. Like Machen, they considered it “more valuable than any other earthly thing.” They have always recoiled at the idea of concentrated coercive power in the hands of a few. This is no longer true.

Christianity, the State, and Civil Society

The peculiar danger of the new right-wing version of this kind of statism is that it often wraps itself in the language of Christianity. Complicating matters, it is true that the Left will call anyone who desires Christian virtue and ethics to have any influence whatsoever in the public square a “Christian Nationalist.” One should rightly scoff at such self-serving, bad-faith labeling. Not everyone who is pro-life or opposes LGBTQ+ advocacy deserves such a sweeping label. At the same time, we should not be blind to the fact that there are people who are “Christian Nationalists” in the sense described: seeking to bring about a Christian society by means of top-down government coercion.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Abraham Kuyper and his band of “neo-Calvinists” wrestled mightily with the question of how a nation with a variety of divergent views could coexist without the violence and bloodshed so historically common on the European continent. Kuyper adamantly resisted the Siren call of authoritarian power-seeking. For him, it was a matter of theological conviction that the political order—particularly the coercive power of the state—must allow the “rain to fall on the just and the unjust.” Equal treatment that reflects God’s equal treatment. Not just liberty for our side, but liberty for all sides, within the bounds of God’s moral law.

“The owner’s servants came to him and said, ‘Sir, didn’t you sow good seed in your field? Where then did the weeds come from?’

“‘An enemy did this,’ he replied.

“The servants asked him, ‘Do you want us to go and pull them up?’

“‘No,’ he answered, ‘because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest. At that time I will tell the harvesters: First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles to be burned; then gather the wheat and bring it into my barn.’” (Matt. 13:27–30 NIV)

There will not be a pure, unmixed society until the end of time. There is no utopia in the present age for either the Left or the Right. For Kuyper, God’s will—the mandate of King Jesus himself—is a polity of freedom, tolerance, and forbearance; an open public square where antagonists can build their own institutions and seek to persuade one another; equality under the law; freedom of religion, conscience, speech, and assembly. For Kuyper, what we call “classical liberalism” is what King Jesus requires of the institution that bears the sword.

Kuyper heard all the objections one hears on the lips of Post-Liberals today. But what about those people? Don’t you know how evil they are? They’re abusing the rules! Whose side are you on? He knew that this commitment to a structurally pluralistic society would be unpopular in some circles. He also knew the dangers. But he didn’t think the dangers were any worse—no, he thought them far less worse—than the dangers of Totalitarianism and Authoritarianism. He was more afraid of an unrestrained, coercive state than he was of kooky ideas. He thought that kooky ideas such as (to use one he couldn’t have imagined) men being able to get pregnant could be dealt with by way of free and unfettered public debate. Let the tares and the wheat show themselves, and let the truth win out. Was he wrong? If he was wrong, it isn’t obvious.

But what if Christians are losing the public debate? What if society seems dead set on careening down a path of decadence, debauchery, and wickedness? Isn’t it time to “Break Glass in Case of Emergency,” by having the state define and enforce the “common good”?—once we’ve taken it over, that is (and only then, presumably). If not the state, what will be the source of the morality and virtue necessary for the maintenance of our civic order? How shall “the people” as an aggregate both attain and maintain the kind of common worldview needed for societal peace and prosperity, if not at the behest and direction of the Almighty State?

The answer, as the American founders understood it, is the people themselves in what we call civil society: cultural associations and institutions cultivated by free people to promote and maintain morality and virtue. Individual liberty from government coercion does not for a moment mean, contra Post-Liberal rhetoric, a lack of community and commonality and social ties that bind. There are myriad institutions that shape and form human beings, and some of them are inescapable—the family, for example (no one chooses them). But civil society encompasses so much more: the church, civic organizations, philanthropic and charitable foundations, educational institutions, industry and trade organizations, the economic marketplace, arts and culture, and more; the whole warp and woof of social fabric is woven by the institutions of a free people. In America, it is free associations that bear the burden of cultivating and inculcating human morality and virtue. We do not look to the state to provide this service—at least Americans are not supposed to. (The modern public education system is a notable and influential—and fundamentally progressive—aberration, and one worth rethinking.)

Ideally, we are to be influenced, tempered, corrected, and shaped as moral persons by our families, our churches, our teachers and professors, our friends, our neighbors, our colleagues and associates, even our beer buddies at the bar. Guys with badges and guns? They are at the very tail end of that line, not the front; and even then their task is limited and constrained.

Sometimes this reliance on civil society doesn’t seem to be working. Immorality and vice are everywhere; one political party seeks to constantly enshrine it in law to lord it over the other half of the country. We are a deeply divided people. We don’t share a common vision or common values. We’ve been morally shaped by antagonistic worldviews.

Whose fault is that? Is it a flaw in our system of government? Our failure or hesitation or cowardice about “wielding power”? Hardly. It is the failure of civil society. That is, a failure of ourselves and our own cultural institutions. It isn’t time to “Break Glass in Case of Emergency.” It’s time to stop finger-pointing and take a good, hard look in the mirror. The old adage that we get the government we deserve is an adage because it’s true.

If it seems (and I’m not conceding this point) that an overwhelming majority of people in this country despise our morality and our virtues, is it not due to our own obvious failures? Our churches have failed. Our schools, colleges, and universities have failed. Our think tanks have failed. Our magazines, our journals, our websites, our podcasts, and our newsletters have failed. Our persuasion has failed.

It’s in just such a moment, confronted with our failure, that some of our intelligentsia, Left and Right, blame the classically liberal order itself and reach for the silver bullet or the “strong man.” Actually, here’s a better metaphor: They reach for the ring of power that will stem the tide, compensate for our cultural impotence, and enable us to wield the levers of government to reward our friends and punish our enemies. Illiberalism—the deep desire to deny others their rights of conscience, belief, and property we ourselves enjoy and to force them to conform to our vision of the common good by way of coercive state power—is the last resort of people who have lost the culture by their own hand. Illiberalism is for cultural losers.

It is better that we resist the “Sirens in stereo” and seek to bolster and grow the great middle they’re squeezing. We should reform our weak institutions and engage again in civil society; that is, we should use our liberty to proclaim the gospel and promote truth, beauty, and goodness in every facet of life and society. If our civil and religious liberties really are, as Machen thought, “more valuable than any other earthly thing,” then it’s an everlasting shame that we wouldn’t exercise those liberties and instead seek the foolhardy shortcut of power and coercion. In order to freely reform and build our institutions, we need the state to be the classically liberal state: the exceptional one that keeps its fingers off the scales and protects our liberty to proclaim the good news.

Footnotes

Tom Holland, Dominion: How The Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic, 2019).

BackJ. Gresham Machen, “The Responsibility of the Church in Our New Age,” Selected Shorter Writings, ed. D. G. Hart (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2004), 365–66.

BackSohrab Ahmari, “Against David French-ism,” First Things, May 29, 2019, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2019/05/against-david-french-ism.

BackJohn Daniel Davidson, “We Need to Stop Calling Ourselves Conservatives,” The Federalist, October 20, 2022, https://thefederalist.com/2022/10/20/we-need-to-stop-calling

Back

-ourselves-conservatives/.Davidson.

Back