As a proud son of the Reformation, I’m probably not the best person to comment on topics as arcane as intra-Catholic liturgical disputes. And yet I can’t help thinking that Pope Francis’s recent decision to restrict the celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass has to be one of the more befuddling decisions of his papacy. No doubt there may be a sense in which the “Extraordinary Form” of the Mass is a spur to schismatic tendencies (an incendiary recent op-ed on the subject by Michael Brendan Dougherty in the New York Times is, perhaps, an unintentional vindication of the Pope’s concerns). But that being said, the Traditional Latin Mass is dearly beloved by the most committed Catholics—the core of any ecclesiastical revival—and it strikes me that this is a rather unusual constituency to choose to alienate.

It was against this backdrop that I read a recent opinion essay by exegetical theology professor Paul Raabe entitled “How Lutheran Hymns Lost Their Monopoly in the Missouri Synod.” His chief target is the Missouri Synod’s decision to promote the Lutheran Service Book, the collection of hymns and orders of worship that occupies LCMS pews around the country, as normative for congregations. Raabe argues bluntly that “[a]verage Americans are not into 16-19th-century classical hymns” and posits that “the rank and file want today’s musical sound”—which he defines as “soft-rock, new country, jazz, rhythm and blues, and a host of other sounds but not classical music.”

The times, as Bob Dylan put it, are a-changing. According to Raabe, “trying to shove German chorales down the throats of today’s Americans simply will not fly” and so it is incumbent upon the LCMS to “compose hymns with today’s sound, with a sound that average Americans would find attractive.” His objection to the contemporary Christian music (“CCM”) that dominates radio airwaves is purely substantive; any concerns here are strictly theological, not musical as such. Hence, for Raabe, “[t]he only way forward is for every generation to raise up hymn composers who can put strong theological wording to the musical sound of today and tomorrow. And if copyright laws permit, put traditional Lutheran hymn-wording to different musical sounds.”

Now, there have certainly been times in my life when organ-driven hymns weren’t my preferred style of worship. But with the benefit of a little more maturity, I’ve come to appreciate the patrimony that was handed down to me—and am able to see the flaws underlying Raabe’s shortsighted invitation to abandon the musical forms of generations past.

First, musical choices are communicative in their own way, beyond simply the words being sung. As Luther biographer Roland Bainton once wrote of “A Mighty Fortress,” “[r]ichly quarried, rugged words set to majestic tones marshal the embattled hosts of heaven. The hymn to the end strains under the overtones of cosmic conflict as the Lord God of Sabaoth smites the prince of darkness grim and vindicates the martyred saints.” So too, the thunderous opening of “Thy Strong Word” is an overpowering, dominant burst of sound to which the congregants add their voices, but that would be just as powerful if the congregation was silent. The hymn, in other words, is musically “freestanding”—a powerful testament to the absolute, independent majesty of the God who calls worlds into being ex nihilo. And the anthemic pulse of “Sing, My Tongue, the Glorious Battle” and the piercing mournfulness of “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded” are integral to evoking the sentiments that the words describe; bold courage and aching sorrow alike flow from the tunes as much as the lyrics. After all, as media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously observed, “the medium is the message.”

Second, history matters. There is a fundamental experiential continuity between the churches my grandparents attended and in which my parents were confirmed and married, and the church in which my own infant son was baptized barely two months ago. Raabe justifies his willingness to jettison the traditional hymn-forms on the grounds that “[i]n this country ‘church’ is forced into a consumer system, a free-market system, a capitalistic system with buyers and sellers,” and that “every congregation and pastor must attract American ‘worship consumers’”—but fails to recognize that these are not, in fact, salutary tendencies. Rootedness requires common traditions handed on through time, not constant “creative destruction” in the name of numerical church growth.

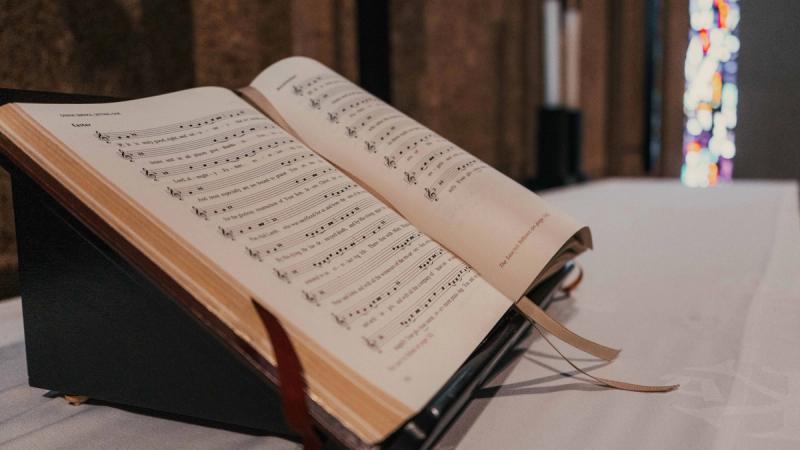

Third, Raabe fails to consider that perhaps, as in the case of the Traditional Latin Mass, there is a deep beauty in the sheer alien-ness of worship that refuses to conform to American cultural norms. For those young people tired of witnessing a Christian media marketplace chase whatever secular trends have proven dominant, churches that stress this mode of worship are quite appealing—indeed, far more appealing than those seeking to cater to popular whim. Some musical forms may be strange to untutored ears, but properly understood their existence is an invitation to learn and appreciate them more deeply, rather than a warrant for reducing worship music to the lowest common denominator. And in its strangeness, this music sets apart and hallows the space through which it resounds. In my own life, such music is (for lack of a better phrase) the soundtrack of sacredness: it instantly communicates to me that this place is different, holy; not a place where we speak and act as we do in the rest of the world.

Of course, Raabe is correct that “[o]rthodox theology can be expressed in different languages and in different kinds of music.” Lutheran traditions have certainly not cornered the market on the instrumental forms that may be used to praise God. But there is a reason these musical settings have endured for so long, and in the midst of a cultural moment longing for stability and authenticity, they can serve both as anchors grounding the church in its eternal purpose and as bridges connecting today’s parishioners to their forerunners in faith. That strikes me as more than enough reason for keeping them firmly in place.

John Ehrett is editor in chief of Conciliar Post, an online publication dedicated to cultivating meaningful dialogue across Christian traditions, and a Patheos columnist writing at Between Two Kingdoms. He is a graduate of Yale Law School and is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in Religion at the Institute of Lutheran Theology.