Ever since at least the 19th century, the notion that Protestants, especially Calvinists, and even more particularly Calvin himself, are and have been obsessed with the doctrine of predestination has been something of an ongoing complaint levied by critics of the Reformed faith. The idea that Calvin’s theology is centered on God’s decree of predestination—that his whole theology arises from this “central dogma”—is still not an uncommon protest against his theology. Whatever one might think about such charges—and I find them to be generally baseless—they usually arise from the polemical history of early modern Protestantism. Some of the Protestant Reformers argued over the doctrine with the Roman Catholic Albert Pighius. And in the following decades the Reformed would again defend their understanding of predestination against the Lutherans and Remonstrants (Arminians) resulting in the so-called Five Points of Calvinism. Because this history is so well-known to us, we might end up thinking that such a history is in fact unique—that the Reformed faith was overly interested in defending and promoting the doctrines of predestination and reprobation. It is this last point I want to challenge. Reformed Protestants were absolutely not the only part of the church in the West dealing with internal and external debate over predestination during the early modern period. Let’s look at some Roman Catholic history.

Baianism

In the middle of the 16th century internal division among Roman Catholics in Europe over predestination began to emerge. This is not to say that such division was not itself an outgrowth of medieval differences. Yet, however much the doctrine of predestination was discussed and even debated among the medieval scholastics, the level of polemical heat among the disparate positions did seem to increase. For example, theological professor at the University of Louvain, Michael de Bay (Baius), was suspected of Calvinistic tendencies by some Franciscans for, among other things, denying free will after the fall and claiming that without grace every action of man is sinful. His son Jacques de Bay (Baius), presumably following his father’s teaching, denied the notion of universal sufficient grace; only those who receive the ministry of the gospel message are granted sufficient grace to believe. The elder de Bay’s teachings were eventually condemned by Pope Pius V in his Bull Ex Omnibus Affectionibus (1567). As these things are wont to happen, the bull, however, did not quell Baianism. In 1585, the Jesuit Leonard Lessius arrived to teach at the University of Louvain only to find that Baianism was being taught at the university. Lessius, who arguably held positions akin to the semi-Pelagian position on free choice, predestination, etc., attacked de Bay. The university, sympathetic to de Bay, followed suit by condemning Lessius’ teaching on predestination and reprobation as Pelagian! The Pope had to step in and effectively told both parties to stop condemning each other.

Congregatio de Auxiliis

A few years previous to Lessius’ arrival at Louvain, a debate ensued among the Jesuits and Dominicans in Spain around the seemingly innocuous question of whether Jesus died freely and thus meritoriously, if the Father appointed him to do so. The question probed the nature of free choice among other questions related to predestination and ended up erupting in chaos among the various Spanish Universities. In 1588, fuel was thrown onto this controversy when Luis de Molina, a Jesuit, published his Concordia, defending his account of predestination, free choice, middle-knowledge, etc. Published in Portugal, it immediately was criticized and pulled from publication by the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal. The book was allowed to be republished (with an added defense by Molina) in the following year yielding further debate. The Pope was forced to step in. Pope Clement VIII decided to form a commission called the Congregatio de Auxiliis (the Synod about the Helps [of grace]) to determine whether Molina’s theology relating to human freedom and predestination was unorthodox or not. After much heated debate from both Jesuits and Dominicans, each discussing their views before the Pope and the Synod which had been formed—and a couple of Popes later—Pope Paul V gave his verdict in 1607. He deemed both views were tenable and that both sides should stop accusing the other of heresy. Thus, the Congregatio was ended, to the chagrin of both sides.

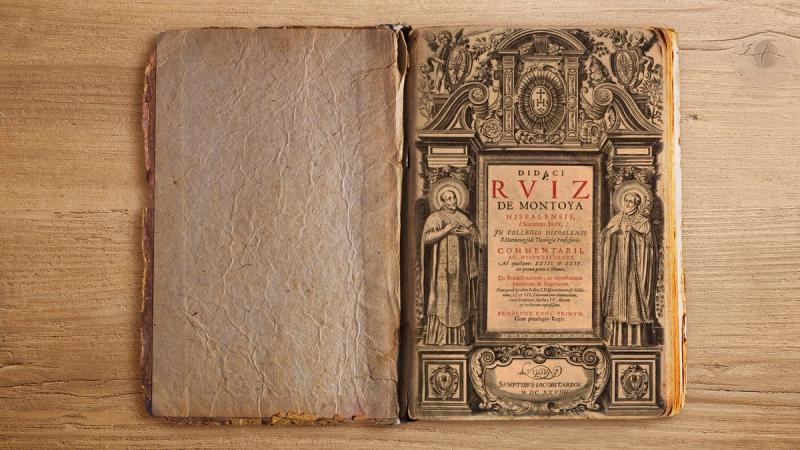

Given this history, a few observations are worth making. First, these controversies help us to understand why so much ink was spilt on the doctrine of predestination among Roman Catholics in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Take this massive tome published by the moderate Jesuit Ruiz de Montoya as a testament to the doctrine’s importance for early Modern Roman Catholics. Second, there is no reason to suggest that Roman Catholics were obsessed with the doctrine even if they wrote far more books on the topic than the Reformed; indeed, they even needed the Pope to form a commission to deal with the controversies. The writings of theologians are often driven by external and/or internal (perceived) attacks on orthodoxy and the early modern period was no exception. For similar reasons, the early church debated Trinitarian and Christological errors. Finally, this history sheds greater light on the fact that the Reformed were not uniquely dealing with perceived threats to the Augustinian doctrines of predestination, free choice, total inability, etc. The Reformed Synod of Dordt and the topics it dealt with were not a result of some overly obsessive Reformed theologians who could not stop thinking about predestination any more than the Congregatio de Auxiliis was a sign of obsessiveness over God’s decree. Doctrines were challenged and polemics resulted.

Dr. Michael Lynch teaches language and humanities at Delaware Valley Classical School in New Castle, DE. He is the author of John Davenant’s Hypothetical Universalism (Oxford University Press, forthcoming)