Of all the questions I asked myself last week, “Is Tim Keller a Marxist?” was not one I anticipated considering. This is a charge I have heard on more than one occasion and, I am told, has recently been repeated in the aftermath of his op-ed in the New York Times.

While we should initially assume for the sake of charity that those making this accusation at him actually know what the terms means, that may not be the case for many of the readers of this post, so a few preliminary definitions-of-terms are therefore in order.

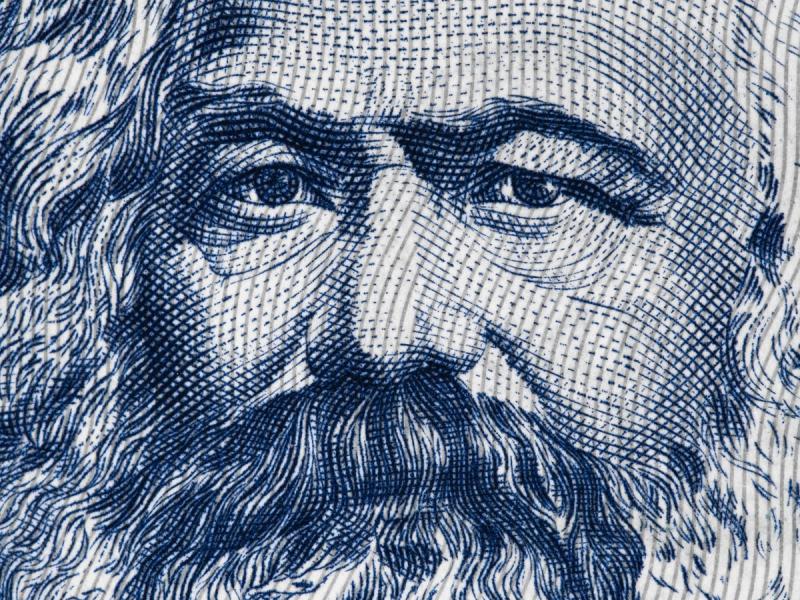

Marxism is notoriously hard to define with precision. If there is one group in the world which can match Christians in its ability to fragment indefinitely and anathematize those who claim its label while deviating on fine points of dogma, it is the Marxists. If we take the term in a narrow, historical sense, we could argue that it refers to those who think (1) that economic relationships are fundamentally constitutive of human identities, and (2) that capitalism as a system of economic organization is doomed at some point in the future to collapse under its own contradictions.

Over the years, many Marxists have accepted the basic idea that capitalism is a stage in history which will pass, but have articulated this in the context of philosophies which have different emphases. Thus, postcolonial theorists have tended to develop Marx’s thought in relation to patterns of political life connected to imperialism, colonialism and the like. For such, categories of race have come to the fore. Classic texts in this area are Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and the late Edward Said’s Orientalism. These provide classic examples of how Marx and the Marxist tradition were placed in service of unmasking the ways and means that those with power have maintained their status through various means—cultural, economic, political. Closely related to these are the sexual liberators like Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse who fused Marx with Freud. This approach found its logical conclusion in the pansexual political theory of a feminist like Shulamith Firestone whose 1970 book, The Dialectic of Sex, is an unabashed application of Marxist and Freudian thought to the matter of revolutionary sexual liberation.

Now, the relationship of these later developments to the original Marx is often somewhat muted. Marx did make some interesting comments on the distinctiveness of what he called ‘the Asiatic mode of production’, and these have been the launchpad for post-colonialists seeking a starting point in his works even as the elaboration of the idea has gone far beyond anything Marx wrote or even thought. For all his radicalism, Marx was a white, European male, after all. But the central core of Marx, that capitalism oppresses the poor and the weak, that it is doomed by its own contradictions to collapse, and that some kind of major economic restructuring of society which abolishes capitalism will be necessary for true human flourishing, is common to all, as is the belief that this paradise will be an exclusively earthly, immanent phenomenon.

There is often a second part to the accusation: Tim Keller is a cultural Marxist. That is an interesting qualification which typically points to that strand of Marxist theory which sees the Italian thinker, Antonio Gramsci, as its fountainhead. Wrestling with the rise of Fascism and the failure of the working class in western Europe to follow the Russian lead and rise in revolution, Gramsci argued that the way to take over was to capture the key cultural institutions—schools, universities, the media, Burke’s ‘little platoons’; those mediating institutions which do so much to shape society—or the law courts. The long march through the institutions would eventually bring about the necessary changes in society. Such had to be carefully planned and executed, but it would be worth it.

This basic groundwork now allows us to address the more accurately-phrased question, “Is Tim Keller a cultural Marxist?”

It is true that Rev. Keller has expressed a concern for what now is typically referred to as social justice. ‘Social justice,’ like ‘cultural Marxism,’ is a term used by far more people—friend and foe—than can actually define it in any coherent way, but, broadly speaking, it is used today to refer to perceived inequalities, be they matters of race, gender, sexuality etc. Now, concern for these issues does not of itself render you a cultural Marxist—most sane people would say that they are opposed to racism, sexism and the like. They may disagree on the definitions of these things and what steps should be taken to address them, but having a social conscience in itself is neither a Marxist monopoly nor a distinctive of the left.

Is Tim Keller a Marxist in how he defines these things? While I have not had the pleasure of asking him personally, I have read statements by him that indicate he believes human beings are made in the image of God. That presumably grounds his ethics. It also places him outside of the Marxist camp, belief in God being somewhat problematic in that school of thought, as (incidentally) is his Christian belief that human beings have a nature which can be defined in metaphysical, rather than contingent, historical terms.

If he is not a Marxist, it does not take a postgraduate qualification in logic to deduce that he can scarcely be a cultural Marxist. Even so, let’s indulge the critics and ask this question: Does Tim Keller’s view of the culture have parallels with the Gramscian tradition? Yes, it does in that he is a cultural transformationalist who believes that the world can be dramatically benefited by—schools, universities etc. So do the Acton Institute, Marvin Olasky and the team at World Magazine and numerous friends and colleagues in First Things circles. I hardly think they would appreciate being given the label of cultural Marxists. To want to change the culture is a desire of anyone who is dissatisfied with the status quo, not a necessary sign of commitment to dialectical materialism or a diabolical hatred of free markets.

Let me be clear—while respecting him as a brother in Christ, I am not an acolyte of Rev. Keller. I disagree at points with both his theology and philosophy of ministry. Nor do I share his love of the city. For me, cities are a necessary evil whose sole purpose is to provide country boys like me somewhere to go to the theatre once in a while. And I am definitely not an optimistic transformationalist as he is—trust me, things are going to get worse before, well, they get even worse than that. But he is no cultural Marxist, and to call him such is to reveal not the politics of the good doctor but the ignorance of the troll. It is to indulge in the spirit of this age, which eschews thoughtful argument about difficult issues for moronic and often malicious soundbites. It is not a helpful way of locating him in current debates in order to further the discussion, but rather a cheap way of pre-emptively delegitimizing him and his opinions. It is an unwarranted slur on his character, for we all know that cultural Marxism is not intended as a morally neutral term. And—I almost forgot—it is to break the Ninth Commandment about a Christian brother. And that’s a sin—not so much a sin against Tim Keller as against the God he serves.

Carl R. Trueman is a professor at the Alva J. Calderwood School of Arts and Letters, Grove City College.