In the former parts of this series (pt. 1, pt. 2, pt. 3), I laid out some basic features of Origen’s Christological exemplarism. More could be said, but Christological exemplarism is clearly an aspect of atonement in Origen’s thought; I say “aspect,” because it is not a “theory” to be marshalled against other theories. As seen, exemplarism co-existed with Christus Victor and so-called “Ransom atonement” in Origen’s thought (if space permitted, I could argue that elements of Penal Substitution are also present).

Christological exemplarism recognizes Christ as the premier pattern of holiness; more than this, it identifies Christ as the end (in the teleological sense) of humanity. Christ is thus more than a good moral model, which any human can be: he is the archetype for humanity. To gaze on the strange glory of Christ the Crucified One is to behold both what the human being is meant to become (i.e., a divine image of human substance) and how to become it (i.e., by taking up one’s cross, crucifying the flesh).

How do we put Christ before us in order to contemplate his person, as a reference for our souls to which they must conform? Where do we go to meet the Logos?

The “Well of Vision” and the Spiritual Sense

Origen uses the image of a well for Scripture; specifically, the “well of vision” where Isaac dwelled (Gen. 25:11). Origen notes that Jacob, Isaac, and Moses all met their wives at a well. Understood according to the spiritual sense, the “well of vision” for our souls is Scripture. There we meet our groom-to-be and drink from the living waters of the Word that he promised.

What does it mean to dwell at the well of vision? Origen replies: “But if anyone rarely comes to church, rarely draws from the fountains of the Scriptures, and dismisses what he hears at once when he departs and is occupied with other affairs, this man does not dwell ‘at the well of vision.’” Origen is describing a basic level of devotion that is expected for all Christians. But there is a special blessing for those who can commit their lives totally to the reading and contemplation of Scripture, as Origen did, and “never withdraws from the well of vision”:

It is the apostle Paul who said: “But we all with open face behold the glory of the Lord” [cf. 1 Cor. 3:18]. You too, therefore, if you shall always search the prophetic visions, if you always inquire, always desire to learn, if you meditate on these things, if you remain in them, you too receive a blessing from the Lord and dwell “at the well of vision.” For the Lord Jesus will appear to you also “in the way” and will open the Scriptures to you so that you may say: “Was not our heart burning within us when he opened to us the Scriptures?” [Luke 24:32]. But he appears to these who think about him and meditate on him and live “in his law day and night” [cf. Ps. 1:2].

Hom. Gen. 11.3

Within Scripture, we find the Logos in the “spiritual sense.” This sense is hidden (yet made available to us through) the “bodily sense” of Scripture, often called the “literal,” “historical,” or “sensible” sense. To be clear, Origen does not suggest we ought to dispense with the bodily sense; it too edifies, and both senses are necessary for the formation of the total human being. However, if read according to the bodily sense alone, the reader only picks out a set of “Jewish stories” (Hom. Lev. 3.3.5) —no doubt interesting and morally instructive stories, but clearly by, for, and about a specific ethnic group exclusively. Origen draws an analogy between Scripture and the Incarnation: If we met Jesus of Nazareth on the streets of Palestine, we would see merely a poor Jewish carpenter. His divinity is invisible to the eye. By the same token, the “divinity” of Scripture is not found by a surface, literal reading. But hidden beneath the surface, we find the “living waters.”[1]

The spiritual sense is where the soul actually meets Christ in Scripture; it is where the word becomes the Word. Reading Scripture according to this sense conforms the soul to the Logos dwelling there. Thus Scripture is an indispensable rule for conforming the soul to Christ.

Origen’s “Allegorism”

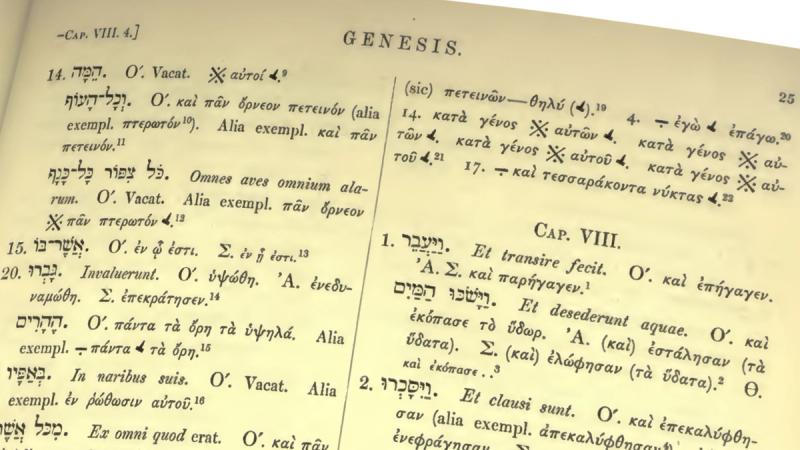

Allegory is an inadequate description for Origen’s exegesis. The literal meaning of the word implies that one meaning (e.g., the literal) is dispensed with for another, more elevated meaning (e.g., the allegorical). This does not describe what Origen does; in fact, he rarely uses the term “allegory” at all. In Origen’s practice, three senses can appear in Scripture: the bodily (i.e., literal, sensible, or historical), the psychic (i.e., soulful or moral), and the pneumatic (i.e., spiritual, divine, Christological, ecclesial, or prophetic). All three senses edify and are required for biblical formation, including the literal sense. Usually, all three senses are present in a single verse, but this is not always the case. Some passages, in fact, entire books of Scripture, may have only one of the three senses. For example, both the Song of Songs and the Book of Revelation, according to Origen, have a purely pneumatic sense, and Psalm 36 has a purely psychic sense.[2] Most psalms, however, have all three senses.

Origen’s exegesis can be complex, so to oversimplify matters, a sense is determined by its object. The bodily sense involves reading the text on its own terms. The psychic sense reads the text in relation to the soul and its journey to God. The pneumatic sense reads the text in relation to the person of Christ, the Church, and their eschatological union. If we understand a sense in terms of its object, then we might think the Gospels are purely bodily: no allegory is required, for the subject of pneumatic reading, Christ, is already present there literally. Put another way, what is pneumatic in the Old Testament is bodily in the New Testament. Origen denies the New Testament lacks any pneumatic sense, but argues it reflects a different dispensation than what we find in the Old Testament: For Origen, the pneumatic sense in the Old Testament is Christological, concerning the Incarnate Christ, whereas the pneumatic sense in the New Testament is eschatological, concerning the future, glorified Christ. Thus every book of Scripture has a pneumatic sense pointing beyond itself prophetically.

There are pastoral “advantages” to reading Scripture this way. For brevity, let’s focus only on the psychic sense. First, it makes the messages of Scripture universal. Take, for example, the verse, “Rejoice before the father of orphans” (Ps. 67:5–6 LXX). How are we to pray this Psalm? Read in its literal sense, this verse brings a word of cheer to orphans in the church; but if the Scriptures are to deliver a word for all in the church, then the psychic sense is required. As we’ve said, the psychic sense consists in reading the verse as pertaining to the soul. Origen initiates a psychic reading by pointing out that “if you understand who the father is from whom you ought to be orphaned…you will see how God is the father of orphans.” Naturally, the “father from whom you ought to be orphaned” is “the father of sinners” (John 8:44), the devil, for “everyone who sins is born of the devil,” says Origen, alluding to 1 John 3:8. By crushing the head of the serpent, God effectively orphans us and then adopts us as his own children. “I suppose,” says Origen, concluding his psychic exposition, “therefore that the orphan is understood as someone whose father is God” (Hom. Ps. 67.2.7). Understood psychically, every convert can be said to be an orphan, thus all can recognize God as “the father of orphans,” and the accompanying command to “rejoice” extends to all. As a result of Origen’s exegesis, every hearer of Scripture can understand this verse in a way that allows her to make it her own. While the literal sense is committed to the particulars, the spiritual sense expands the pastoral capacity of Scripture, making all of Scripture for all.

The second pastoral advantage of the psychic sense is that Scripture becomes contemporary; that is, it is no longer read as mere reports of events and persons from time past, but it describes the immediate drama of our salvation. Take Origen’s eighth homily on Genesis. The text is Abraham sacrificing his son, Isaac. As always, Origen begins in the literal sense:

Since everything was done in the mountains, was there thus no mountain nearby, but a journey is prolonged for three days and during the whole three days the parent’s heart is tormented with recurring anxieties, so that the father might consider the son in this whole lengthy period, that he might partake of food with him, that the child might weigh in his father’s embraces for so many nights, might cling to his breast, might lie in his bosom? Behold to what an extent the test is heaped up!

Hom. Gen. 8.4

This interest and sympathy for Abraham’s psychological state reflects Origen’s commitment to the literal sense. Origen does not think one sense exists at the expense of the others: Origen clearly appreciates Abraham as a godly historical figure, not merely as an analogy for the soul. Pausing to address the fathers in the assembly, particularly those who had lost a child, Origen explains that Abraham is an exemplar to them, but adds that if we stick to the literal sense, Abraham is little more than an unachievable picture of magnanimity: “This greatness of soul is not required of you, that you yourself should bind your son, you yourself tie him, you yourself prepare the sword, you yourself slay your only son. All these services are not asked of you” (Hom. Gen. 8.4). Read in its literal sense, we are not required to “become Abrahams” and offer up our sons. Yet read according to the psychic sense, Scripture supplies the terms for our own spiritual sacrifice. Origen initiates the psychic reading of the story by asking:

Do you wish to see that this is required of you? In the Gospel, the Lord says: “If you were the children of Abraham, you would do the works surely of Abraham” [cf. John 8:39]. Behold, this is a work of Abraham. Do the works which Abraham did…But also if you should be so inclined to God, it will be said also to you… “Offer your son,” not in the depth of the earth nor “in the vale of tears” [cf. Ps. 83:7], but in the high and lofty mountains. Show that faith in God is stronger than the affection of the flesh. For Abraham loved Isaac his son, the text says, but he placed the love of God before the love of the flesh and he is found not with the affection of the flesh, but “with the affection of Christ” [cf. Phil. 1:8], that is with the affection of the Word of God and of the truth and wisdom.

Hom. Gen. 8.7; emphasis mine

In this reading, Isaac is our flesh: not the sinful Pauline sense of the flesh, but the natural bonds of family, friends, and nation. Abraham sacrificing his son understood in terms of the soul is thus the act of conversion, of making Christ our chief affection. In this way, what is said to Abraham— “Offer your son to me” [Gen. 22:2]—reaches across history and is spoken directly to me, and I can become “an Abraham” myself by doing as he did. Without the psychic sense, how can I possibly hear and obey the exhortation of John 8:39 to become a child of Abraham by doing the works of Abraham? Origen suggests this is the reason such things were written in the first place:

But these things are written on account of you, because you too indeed have believed in God, but unless you shall fulfill “the works of faith” [2 Thess. 1:11], unless you shall be obedient to all the commands, even the more difficult ones, unless you shall offer sacrifice and show that you place neither father nor mother nor sons before God [cf. Matt. 10:37], you will not know that you fear God nor will it be said of you: “Now I know that you fear God” [Gen. 22:2].

Hom. Gen. 8.8; emphasis mine

Instead of a summary lesson, Origen habitually concludes an exposition of a section as he did above: by repeating something said by or to someone in Scripture as though it were said by or to the listener. Unlike much modern pastoral exegesis, Origen does not think Scripture is a “source” for crafting “biblical” applications to our lives: Scripture is its own reality, which its inspired nature permits us to inhabit. In this way, the events and characters (and wonders) of Scripture become contemporaneous with the soul, and the soul works out her salvation in the very act of hearing and contemplating the biblical narrative. The goal is not merely to derive a useful lesson from Scripture (a book need not be inspired for us to do this, after all: it can be done with The Iliad, or The Very Hungry Caterpillar!), but to enter Scripture; indeed, to become Scripture by writing it on the heart and, in this way, transforming the self into a walking Bible. “Let us gather as far as we are able the words of Scripture,” exhorts Origen, “that we may lay them up in our hearts, and try to live them…” (Hom. Jer. 2.3; emphasis mine).

Conclusion

Origen’s pastoral concerns explain many aspects of his exegesis. In order to execute the universal and contemporary applications of the spiritual sense, the first order of business is identifying the speaker of any particular verse. When expositing the Psalms, the premier voices we are to make our own is that of the Psalmist—inevitably David, but occasionally Christ himself. This establishes the “literal” or “sensible” sense of the Psalm on which we can build, “for the sensible things become a ladder towards understanding greater things. Therefore, the whole Scripture speaks in sensible terms, so that we may step up on them to spiritual things. And if Scripture had not spoken the law sensibly, we would not have originally been able to say, ‘For I know that the law is spiritual’ [Rom. 7:14]” (Hom. Ps. 67.2.4). The literal sense is the unavoidable first principle of exegesis which makes the other sense available to our human understanding. But the voice of the Psalmist does not become spiritual until we can make it our own, for to “reflect spiritually as a spiritual person” is to know “what has been spoken” by the Psalmist and “to speak it with nearly the same standpoint as he did” (Hom. Ps. 67.2.5). For this reason, it is a mistake to study Origen as though he were a philosopher or a systematic theologian. His goal is not to construct a grand theoretical system of theology, but to build up of the Church and conform her members to Christ. He is, first and foremost, a pastor.

[1] Origen is not suggesting that the presence of the Word in the word is a second Incarnation, but that Scripture is a sacrament or “sign” of the Incarnation. The closest analog is the Eucharist. The presence of the Word in Eucharist, Scripture, and Incarnation is the same one Logos, but each serves a different economy.

[2] Thus we must exempt Origen from the accusation often levied against “allegorical,” “spiritual,” or “Christological” exegesis that attempts to find Christ in every single line of Scripture.