I’m telling you: Everything on Ardnamurchan Peninsula is dramatic and remote. The most westerly point of mainland Britain, perched on Scotland’s coast, has seemingly eluded time. Vast moorlands, deserted beaches, fjord-like lochs compete only with otters, whales, and white-tailed sea eagles for the attention of guests at romantic isolated inns such as Kilcamb Lodge Hotel. Some years ago, during an extremely low tide, the hotelier spotted a gigantic mushroom-shaped anchor along the shore. Divers retrieved it; experts investigated it. In the end, the artifact was not a medieval relic of daring Norse travelers, as some might have thought, but instead important material evidence for what insiders to historical shoptalk now call the “Long Reformation”: a physical record that directly ties the work and worlds of Luther and Calvin, Knox and Zwingli, Bucer and Tyndale to much later periods—even beyond the Enlightenment.

This particular anchor dates from the middle of the nineteenth century and belonged to, of all things, a Protestant church. In the Disruption of 1843, one-third of the ministers in the Church of Scotland left their denomination because of state interference in ecclesiastical matters and formed the Free Church of Scotland—a confessional Presbyterian body committed to the spiritual independence of the church, a doctrine with deep roots in the Reformation. The fledgling Free Church immediately faced a serious problem: the hostile attitude of landed proprietors. Congregations had to gain approval, if not goodwill, from landowners on whom they largely depended to grant them new sites for worship. Yet, many landowners initially remained sympathetic to the mainline Church of Scotland or even belonged to the Episcopal Church. When the appeals of Free Church communities met with refusal, they carried on by worshiping on public roads in the Highlands, in gravel pits on the Isle of Mull, in distilleries near Campbeltown. All along the north, east, and west coasts, they gathered on intertidal zones—wet patches of sand, exposed only when the tides were out, that belonged to everyone and no one because they were legally considered part of the sea. Because their true-covenant Lord had summoned them to worship, congregations assembled wherever they could, whatever the cost. These displaced Scots might have recalled fondly the old saying “Presbyterianism is no religion for a gentleman” and worn it gladly.

In 1845, the Free Church General Assembly set up a committee to tackle the problem of site refusal. “It happens that in almost all places where sites are urgently required, churches may be built in a fashion differently from that we have been accustomed to,” Robert Candlish, a leading Free Church minister, told fellow ministers. On Ardnamurchan Peninsula, the obstacles seemed insuperable, for on it sat the estate of Sir James Riddell, proprietor of over 100,000 acres. Sir James was a well-traveled man, a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He had little in common with his tenantry. They were mostly Gaelic-speaking Presbyterians; he was an Episcopalian who wanted no Free Church near his mansion house at Strontian on the eastern end of Loch Sunart. A tentative compromise was reached to permit the church at Strontian use of a tent in winter. When Riddell hedged with even more conditions, the agreement foundered.

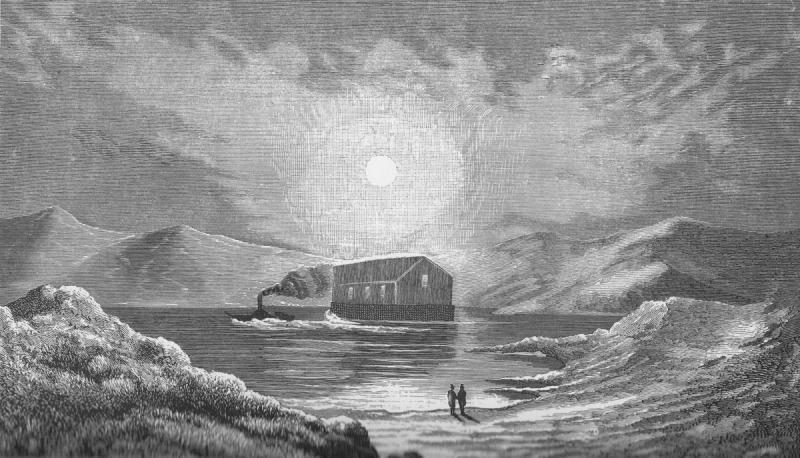

In response, the General Assembly authorized a unique “naval policy.” It would build a floating church that could be moored offshore in areas where sites were refused. The Sites Committee contracted with the Port Glasgow shipyard of John Reid & Company for a large iron church, a kind of corrugated shed on a barge. The committee chairman observed,

We have only ordered one, because it is an experiment. I sincerely trust, and I am sure the Commission will unite with me in prayer to God, that this vessel, to be launched to preserve His testimony, may be preserved, that this ark, for the preservation of His own Word among our distant congregations, may be kept safe on the bosom of the deep, until the waters of bitterness have subsided, and peace be restored, when the congregations, returning each to his own sequestered vale or hillside, may then be permitted to erect their own tabernacle, and to send forth their praises to Him who, through much suffering and tribulation, has brought them to see His great salvation.

In July 1846, the steamer Conqueror towed the floating church up the River Clyde to Loch Sunart. Enthralled villagers gawked from housetops and waved handkerchiefs as though celebrating a victory in war. The obvious place to deploy this new dreadnought was underneath the windows of Sir James’s coastal mansion—but they decided not to risk provoking Sir James more than necessary. Instead, the floating church was moored about a mile from Strontian, a hundred and fifty yards offshore.

At the first Sunday morning service, between the hours of ten and twelve, the congregation was ferried out for public worship. A visitor described the church as

not only commodious, but in every respect comfortable; and one could almost imagine himself, when seated therein, as listening to the ministrations of the gospel in one of the neater churches of the metropolis. The peculiarity, however, of the mode of ingress and egress brought vividly but sadly before my mind the melancholy fact, that an otherwise humane Scottish proprietor should so little sympathise with the religious feeling of his tenantry, as to compel them, after worshipping for three years on the shelterless hillside, to seek at last, for conscience’s sake, a place of refuge on the sea.

The church was indeed strange. With a low freeboard and high superstructure, it looked like what it was designed to be: a building that could float. The congregation entered from the stern of the vessel, and a pulpit and vestry were at the bow. Benches could seat seven hundred. There was a gauge fixed to the bow that measured church attendance by how much the church sank in the water. Three skylights provided the only source of illumination.

Yet for all its strangeness, the floating worship space was also extraordinary. One contemporaneous minister, Rev. Finlay Macpherson, recalled the experience:

No one can scarcely enter it without feeling a peculiar solemnity remembering the cause for which this devoted and interesting congregation have been compelled thus to assemble there and to worship their God on the bosom of the deep. In stormy weather it is rather inconvenient and it is always tedious for such a large congregation to get on board and afterwards to get ashore. When I preached there the day was very short so that the darkness of night was coming on before we could leave the Floating Church and notwithstanding the provision made by having good boats in attendance and strong cables fixed to the shore the passage tho’ short was rather unpleasant, the boats being much crowded and the shore so rocky and rough and slippery as a landing place.

On several occasions, the Iron Church at Strontian nearly broke free from its tethers. Extra anchors arrived from Glasgow to secure the vessel—in fact, it is likely one of these supplementary supports that the Kilcamb Lodge hotelier eventually discovered. When the church finally crashed ashore in a heavy gale after more than a year in service, Sir James agreed to let it remain there on dry land: Ardnamurchan became Ararat. For almost thirty years, the congregation continued to worship in the church-boat, no longer floating but embedded in the beach, until a new building was constructed in 1873 and the old ship went to the scrapyard.

As the flagship of the Free Church “navy” served a particular purpose, there would be no large fleet. Floating iron churches did not come cheap. Any church with its hull in the water was liable, moreover, to incur high maintenance costs. But the achievement of the Floating Church has endured far beyond its actual lifespan. It testifies to basic Reformation principles in nineteenth-century Highlands garb: the necessity of the church gathering to worship, the freedom and spiritual independence of the church, and the collective determination to make provision for distant congregations in need. For good reason, it is remembered as a fitting “house of God,” an “extraordinary Bethel.”

Footnotes

“Reminder of famous Floating Church surfaces,” The Herald, May 21, 2000, https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12241022.remainder-of-famous-floating-church-surfaces; “Bid to raise last relic of Strontian’s floating kirk,” BBC News, November 1, 2016, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-37825362.

BackSee, e.g., Nicholas Tyacke, ed., England’s Long Reformation 1500–1800 (London: UCL Press, 1998); Peter G. Wallace, The Long European Reformation: Religion, Political Conflict, and the Search for Conformity, 1350–1750 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004); John McCallum, ed., Scotland’s Long Reformation: New Perspectives on Scottish Religion, c.1500–c.1660 (Leiden: Brill, 2016); Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, ed., Lived Religion and the Long Reformation in Northern Europe, c.1300–1700 (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

BackThomas Brown, Annals of the Disruption; with Extracts from the Narratives of Ministers who Left the Scottish Establishment in 1843 (Edinburgh: MacNiven & Wallace, 1893), 420–45; N. L. Walker, Chapters from the History of the Free Church of Scotland (Edinburgh: Oliphant, 1895), 41–47. For one broad contemporary perspective, see Allan W. MacColl, Land, Faith and the Crofting Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

BackLionel A. Ritchie, “The Floating Church of Loch Sunart,” Records of the Scottish Church History Society 22 (1985): 159–73.

BackWitness (November 22, 1854).

BackScottish Guardian (July 24, 1846).

BackWitness (July 22, 1846).

BackBrown, Annals of the Disruption, 655–57.

BackQuoted in Ritchie, “The Floating Church of Loch Sunart,” 170.

BackAlastair Cameron, The Floating Church of Strontian (Oban, UK: The Oban Times, 1953).

BackSee, e.g., Acts of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, 1889–1893 (Edinburgh, 1893),422 (June 2, 1891).

Back