Alexander Solzhenitsyn began his 1970 Nobel lecture with a striking image, saying that we moderns hold art as a “puzzled savage” holds some newfound but obscure object, not knowing whence it came or able to dream of its higher function. We misuse it for wealth, for pleasure, for power. We use it “for all the passing needs of politics and narrow-minded social ends.” Still, for all our misuse, says Solzhenitsyn, “art is not defiled by our efforts, neither does it thereby depart from its true nature, but on each occasion and in each application it gives to us a part of its secret inner light.” That inner light most often goes under the moniker of “Beauty.” And “Beauty,” he says, repeating a line from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, “will save the world.”

As Christians, we have a surface-level reason to object. Of course, “Beauty” won’t save the world. Yet, there is a deeper-level reason to affirm Dostoevsky’s hopeful remark. The Christian tradition has a history of understanding God as Beauty itself. That is, Beauty is God considered under the aspect of the Good and the True. It is, therefore, true that “Beauty will save the world.”

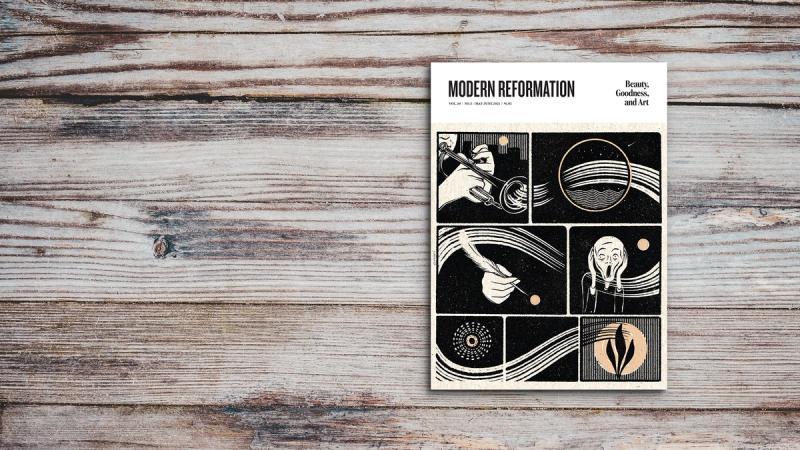

If this Christian tradition is correct, then our contemplation of beauty manifest in art isn’t simply our contemplation of a form of entertainment—there’s something richly theological about it. In this issue of Modern Reformation, we excavate some of those theological gold nuggets that lie under the surface of art’s cultural crust. In our first feature, Bo Helmich explores the nature of Beauty from a Protestant perspective, showing just how significant it is for doing theology. He then asks a very Solzhenitsyn-like question: How might a renewal of Beauty in theology be brought about?

Recently, many fascinating works on the relation of music and theology have been published. It is this theme that our second and third features discuss. Steve Guthrie offers a theological interpretation of music, while noting its application to the current epidemic of loneliness. And David Wilmington argues that jazz offers a unique analogy for thinking about ethics, particularly in our post-Kantian and postmodern context.

Francis Schaeffer used to say that the Christian community tends to look at modern art with a snicker when there is reason for tears—meaning that contemporary art often provides for us a window into the depths of human despair, and that is no laughing matter. In our fourth feature, Daniel Siedell similarly admonishes us, taking as his particular example Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream. This work, as with much modern art, ought to be viewed as a visual lament. Seen with the eyes of faith, though, Siedell reminds us, lament does not have the last word.

As you take up this issue dedicated to the arts, we pray you will look anew at the multitude of creative gifts God has provided to his people, and by them gain some glimpse of the beauty of the Lord (Ps. 27:4).

Joshua Schendel executive editor